Stan Tracey, Translator?

by Samuel E. Martin

Perhaps now we can more readily conceive of a translation of Dylan Thomas into a medium (in this case, jazz quartet) that moves beyond words altogether.

On a sunny Sunday afternoon in spring, I attended a guitar recital in the large hall of a community music school in Philadelphia. Having arrived well in advance, I claimed a folding chair in the front row, where I was soon joined by a congenial couple who began making conversation by inquiring if I was a guitarist myself. Alas, no, I admitted. And what about them – did either of them play an instrument? After a thoughtful pause, which made it clear that the reply wasn’t some sort of rehearsed bon mot, the woman said with a chuckle, “I play the radio.”

There wasn’t time to pursue our chat before an acquaintance of theirs intervened, but had there been, I might have tried to tell my neighbor how perfectly her remark chimed with the book I happened to have finished reading not long before, Peter Szendy’s Listen: A History of Our Ears, in Charlotte Mandell’s exquisite English translation. Szendy is full of insight about the ways we actively listen to music (especially with the aid of recent technology, radio included), playing it and playing with it, adapting it to and for our own devices. His book stems from a basic impulse that nevertheless poses a philosophical conundrum: how, he asks, can we transmit a listening experience? While I possess none of Szendy’s musicological assurance, I’d like to try translating and transmitting one such experience of my own – or, more precisely, to account for being on the receiving end of someone else’s musical listening that is already (perhaps) a translation.

To begin again, then, with radio and play… The two words are often combined in that order when it comes to classifying Under Milk Wood, the lyrical, irreverent masterwork that the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas had all but completed by the time of his death in November 1953, just days after his 39th birthday. Both terms, however, can stand to be qualified. Under Milk Wood’s standard subtitle, A Play for Voices, hints that the work can exist – and, indeed, is most often performed – away from radio, however conducive to it the text may be. So much for the medium; as for the genre, the BBC, who first broadcast the work in January 1954, was in the habit of distinguishing between conventionally plot-driven “radio plays” and more nebulous “radio features.” Under Milk Wood’s free-flowing invention, verbalizing the dream cycle and daily routines of the residents of a fictional fishing village in Wales, defies the first category but easily fits the second. Dylan Thomas, meanwhile, had a further suggestion of his own. In a 1951 letter detailing his work in progress, he ventured the idea of “an impression for voices” (CL 906). Imogen Cassels splendidly unfolds the potential layers of meaning that “impression” contains, from “impressions of stock figures” (i.e. the quirky inhabitants of the town of Llareggub) to the impressionistic soundscape that Thomas conjures through language (RC 66). To this, I would add the very literal sense in which, via phonographic technology, an impression for voices becomes an impression of voices, sound wave signals etched onto a receptive surface. Pressing the point, we might say that a vinyl recording of Under Milk Wood realizes Thomas’s prophecy for his work in at least one way that an ephemeral radio broadcast cannot.

It was in its LP incarnation, at any rate, that Under Milk Wood first reached the ears of the maverick English jazz pianist Stan Tracey, some 10 years after the death of its author. So galvanizing was its effect that Tracey took it upon himself to author his own version within his chosen idiom. The Under Milk Wood-inspired Jazz Suite that the Stan Tracey Quartet recorded and released as an album in 1965 has long since taken its place in the pantheon of 20th-century popular music, yet its iconic status doesn’t make it any easier to pin down than the work that sparked it. If we sidestep the definitional morass of “jazz,” “suite” may at first appear more straightforward, but we soon find ourselves spinning round along with the record. Stan Tracey’s work is a suite both in the accepted English sense of an instrumental composition comprising several parts and in the French sense of a continuation, a following on: Jazz Suite follows Under Milk Wood, yes, prolonging something of it – and Under Milk Wood thereby follows Jazz Suite into the realm of nonverbal music. Since that leaves us no closer to understanding where the two works stand (or move) in relation to one another, let’s listen to Stan Tracey himself, announcing a performance of Jazz Suite on Hamburg radio in 1966:

The music you are about to hear is a suite based on Under Milk Wood, a play for voices by Dylan Thomas. I first heard this work on a recorded production which was narrated by Dylan Thomas himself. Since then I have heard it many times, and each time I have been deeply impressed by its beauty. Last year I was invited to write a jazz suite, and I took this opportunity to translate into jazz the impressions that Under Milk Wood had made on me. [“Introduction,” UMWH; emphasis added]

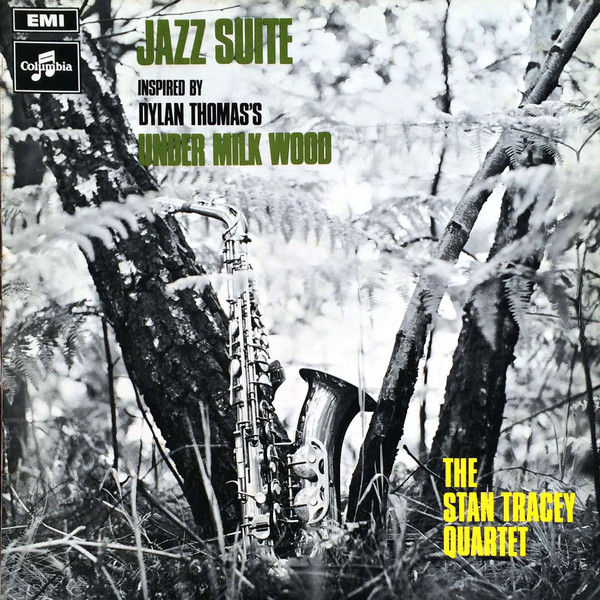

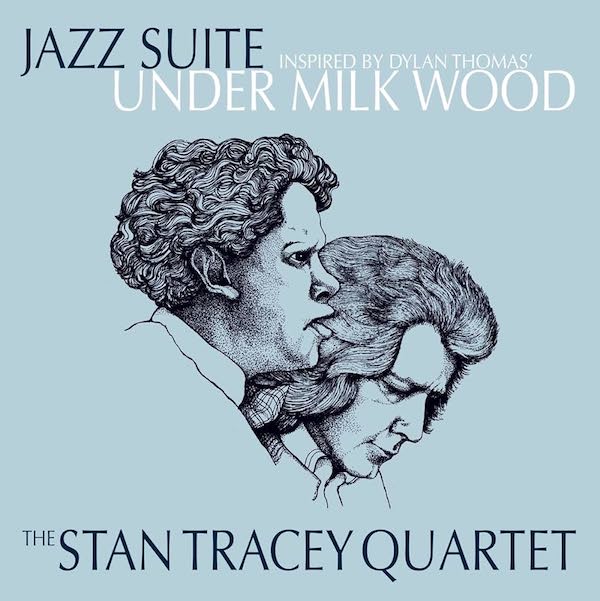

So: a translation of impressions of an impression… We seem to have retreated further into vagueness. But we can take Tracey’s uses of “impress” to mean something just as tangible as Thomas’s: the pianist was marked by what he heard and preserved the resulting grooves in his own recorded composition. Jazz Suite constitutes a clear instance of a musician “writing his listening,” as Peter Szendy says of Liszt and Schumann in a chapter on musical arrangements (“Writing Our Listenings: Arrangement, Translation, Criticism,” L 35-68). The album’s cover illustration by Margaret Parker, which has featured on most of the reissues since 1976, juxtaposes poet and pianist in a way that suggests the former whispering into the latter’s ear; Tracey’s head is bowed, presumably over a keyboard or a writing table, as if he were taking dictation.

And translation? How far do we wish to push our interrogation of Tracey’s other metaphor? Before proceeding, we ought to remind ourselves of two things: first, that Tracey never claims to have translated Under Milk Wood, only his impressions of it; and second, that in the years following the album’s release he tended to downplay its connection to Dylan Thomas, sometimes passing it off as a mere gimmick. Yet that pair of caveats needn’t prevent us from considering the extent to which Tracey’s suite is received as a translation, but also the ways in which it may even behave like one. My hope in pursuing this tack is less to shed my own light on both works in question than to underscore – and understand – how they shed light on one another.

The first thing to note is the haste with which commentators continue to designate Tracey’s suite as a work of specifically British jazz. One can perhaps imagine American critics doing so out of a kind of territorial impulse, conscious or otherwise – but critics in the UK, too, rather than situating the work within the context of mid-1960s American post-bop, have insisted that Tracey’s quartet was operating in its own regional idiom. Duncan Heining, in his study of British jazz from 1960 to 1975, sets out to establish what that might mean:

So, how is it “British”? First of all, there is its choice of subject matter. Second, there is its deliberate evocation of a world and terrain that is self-consciously Welsh, but would apply equally to small town or village life anywhere in mainland Britain during the fifties or sixties. Thomas’s characters and all their eccentricities are immediately familiar to any of us who have lived outside larger urban conurbations. [TD 80-81]

In an earlier paragraph, Heining goes out of his way to correct the editors of The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings, which had misleadingly called Tracey’s suite a “setting” of Dylan Thomas’s play. If anything, that makes it all the more curious that Heining’s own assessment, with its talk of “subject matter” and “characters,” should describe the music in such overtly representational terms. One could go so far as to question whether he is actually describing the music at all. If we take Heining at his word, a listener to the Jazz Suite should somehow be able to discern Thomas’s words through this particular interplay of piano, saxophone, bass, and drums, as though Stan Tracey had managed to translate a British “village voice” distinct from the one emanating from New York in those years of the mid-century.

Alyn Shipton, meanwhile, in A New History of Jazz, points to the Jazz Suite’s supposedly national character as its primary virtue:

What works best about this music is its Britishness. It adopts American concepts of swing and jazz harmony, but tenorist Bobby Wellins’s lyrical improvisation, Tracey’s own acerbic piano (albeit Monk and Ellington-derived) and the backing of bassist Jeff Clyne and drummer Jackie Dougan, add up to something undeniably British and refreshingly original. [NHJ 704]

Shipton seems intent on framing the British specificity of Tracey’s suite in musical terms, and yet every aspect of the composition and performance that he mentions ends up undermining his claim. The music’s inherent Britishness would appear to be all too deniable – unless, of course, it were connected to source material by a British author. Sure enough, whereas Duncan Heining makes the rather dubious case that the suite translates the people and places of Under Milk Wood, Shipton affirms more plausibly (though without elaborating) that the Jazz Suite “[seems] to reflect the richness and variety of Thomas’s language.”

That variety is precisely why, for my part, I would prefer to hear Tracey’s suite, not as a confirmation, but rather as a complication of “Britishness,” much as Under Milk Wood is to begin with. Insofar as “British” is a linguistic category, it is anything but stable, certainly where Dylan Thomas’s work is concerned. The very name of Llareggub, by Welshifying an English expression (it is famously an inversion of “bugger all”), hangs in a multilingual tension that permeates the play, whose audacious punning and 24-hour premise, moreover, owe much to James Joyce’s Ulysses, a book full of similar Anglo-Celtic entanglements. It’s worth recalling, too, that audiences first encountered Under Milk Wood as an internationally inflected work: the New York premiere in May 1953 featured Dylan Thomas as the sole Welsh voice amid an American cast, and it was that version that served as Stan Tracey’s point of departure, not the celebrated BBC broadcast of January 1954 with Richard Burton leading an all-Welsh ensemble. Bearing in mind the border-crossing blend of voices at Tracey’s ear, from Duke Ellington to Dylan Thomas to the Tracey Quartet’s own Scottish saxophonist Bobby Wellins, we can say that the Jazz Suite, far from reaffirming the “self-conscious Welshness” of Thomas’s play, in fact throws its linguistic and cultural mixity into relief.

I wonder if there aren’t other grounds on which to assert a continuity between the two men’s works – structural grounds, you could almost say, though not in a strict chronological sense. The Jazz Suite, at least in its initial album version, starts on a much more sprightly note than the play: the head of “Cockle Row” nods to American composer Jimmy McHugh’s easygoing swing standard “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” orienting the listener to the music’s transatlantic topography. It is, however, the shadowy piano chords leading into the album’s second track, “Starless and Bible Black,” that reset the scene and approach the atmosphere of Under Milk Wood’s celebrated opening monologue:

To begin at the beginning:

It is spring, moonless night in the small town, starless and bible-black, the cobblestreets silent and the hunched, courters’-and-rabbits’ wood limping invisible down to the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboat-bobbing sea. […]

Listen. It is night moving in the streets, the processional salt slow musical wind in Coronation Street and Cockle Row, it is the grass growing on Llareggub Hill, dewfall, starfall, the sleep of birds in Milk Wood. [UMW 3-4]

One could maintain that Stan Tracey’s piano in “Starless and Bible Black” provides as near an instrumental translation as could be imagined of “the processional salt slow musical wind”; I don’t object to the analogy myself. But what I had in mind when hazarding the notion of a structural continuity between Thomas’s play and Tracey’s suite was how the music effectively translates and performs the First Voice’s injunction, repeated throughout the prologue, to listen. Peter Szendy, in the prelude to his book of that very title (Listen), writes of the way in which every musical work seems to demand the absolute attentiveness of its listener, and of his desire to testify to the singularity of his listening. “Except: How can a listening become my own, identifiable as my own, while still continuing to answer to the unconditional injunction of a you must?” (L 3). The First Voice of Under Milk Wood speaks to just such a paradox (“And you alone can hear the invisible starfall,” “Only you can hear the houses sleeping in the streets,” and so on), albeit in a non-musical context: the monologue draws its audience together as it spreads across the airwaves, and at the same time it makes an exclusive claim on each member of this new community, all but explicitly reminding us that there are as many unique listenings as there are listeners. Stan Tracey, then, simply signs his own listening by entrusting it to the instrumental medium of his quartet, which enfolds and isolates its listeners in turn.

If the Jazz Suite features a prelude to the (re)opening movement of “Starless and Bible Black,” Under Milk Wood similarly begins before beginning at the beginning, at least in its book form. Between brackets at the top of the first page appears the word “[Silence].” For all the indispensable insights contained in Walford Davies’s introduction to the definitive edition of the play, I disagree with his characterization of this silence as an inherent “threat” to the ensuing work. I’m far more inclined to concur with Jean-Christophe Bailly when he likens it to the silence summoned by John Cage in 4’33’’, which was first heard (yes, heard) in New York a matter of months before Dylan Thomas and company premiered Under Milk Wood. It is, in other words, a generative rather than a suppressive silence, one that gives rise to the text rather than looming over it; it subtends the words “like a kind of hollow or crevasse across which the voices have to stretch” (S 156), thereby amplifying their resonance.

As I ponder the different forms that this word-loud silence can take in a given incarnation of Thomas’s play, I recall my mother’s account of the first production of Under Milk Wood that she ever attended. It was performed several decades ago at the Brunton Theatre in Musselburgh; accompanying the troupe of voice actors on the stage was a signer who rendered all of the roles in BSL. I marvel to imagine that person’s performance, which not only gives another meaning to what Peter Szendy (in Charlotte Mandell’s translation) calls “signing a listening” (L 35), but which could justly be thought of as having translated Under Milk Wood back into the silence that engenders every vocalized rendition of the play. Not threat, no, but potency and possibility.

Returning to Stan Tracey’s suite and the lush nocturnal quiet of “Starless and Bible Black” in particular, perhaps now we can more readily conceive of a translation of Dylan Thomas into a medium (in this case, jazz quartet) that moves beyond words altogether. As it happens, Thomas fleetingly gestures in that direction himself, in a line that did not survive in the published version of Under Milk Wood but that was still there when the New York cast recorded the 1953 performance that became Stan Tracey’s point of reference: “Mrs Rose-Cottage’s eldest, Mae, is dreaming of tall, tower, white, furnace, cave, flower, ferret, waterfall, sigh, without any words at all” (UMW xliii). Likewise, the Tracey Quartet creates a wordless dreamscape imbued, as it were, with reminiscences of language: a textural if not a textual rendering of the words. And in this regard, the interplay between the quartet’s pair of main voices – Stan Tracey’s piano and Bobby Wellins’s tenor saxophone – is especially suggestive.

The mere presence of two lead instruments in the Jazz Suite replicates Under Milk Wood’s partition of the narrative structure between a First Voice and a Second Voice. Walford Davies’s edition of the play merges the voices into one, pointing out that while the dual structure yields a more manageable quantity of text for any one actor to handle, there is no qualitative difference to speak of between the two vocal strands. Of course, the same could not be said of a pairing of musical instruments. The contrasting timbres of Tracey’s piano and Wellins’s warm tenor combine to flesh out the sound picture beautifully, and the two men’s musical empathy and mutual anticipation (about which much has been said) turn what is effectively a shared monologue by the First and Second Voices into a genuine exchange. Even more uncanny, though, is the way Wellins’s phrasing in “Starless and Bible Black” manages to encapsulate a whole range of voices – or, better still, to convey the mode of appearance of the various voices of Under Milk Wood. Imogen Cassels and Jean-Christophe Bailly use similar metaphors to describe how the voices of Llareggub’s dreaming inhabitants spring up on all sides from the darkness: Cassels refers to the play’s “aural pointillism” (RC 67), Bailly to the “sonic acupuncture of a little Welsh seaside town [where] each point is a voice” (S 149). As for Bobby Wellins’s solo after the solemn legato introduction, it is punctuated by a series of hoots, toots, murmurs, and trills, snatches of melody that pop up like so many utterances and are held together by the rhythm section’s underlying pulse. Although plainly not a translation of what Under Milk Wood’s characters actually say, the solo captures something of – to borrow a phrase from an earlier poem by Dylan Thomas – the play’s color of saying.

Lest my listening of the Jazz Suite seem at all far-fetched (but I’ll sign it just the same!), this would be a good time to remember once again that we are dealing with Stan Tracey’s translation of his impressions of Thomas’s work. By the same token, Bobby Wellins’s improvisations in “Starless and Bible Black” give a singular impression of translation. Any attempt at a more rigorous argument (pace Duncan Heining) is as tenuous as it is unnecessary. For one thing, I’m not aware that anyone in the Tracey Quartet apart from Stan himself had even listened to the play before they recorded the suite. I think I might prefer it that way, after all, since it then becomes possible to hear Wellins’s phrasings as an unconscious extension and translation of the voices of Under Milk Wood, as one more dream in the Llareggub night.

Tracey’s own contributions, as both composer and performer, remain within conscious touching distance of Thomas, sometimes seeking musical illustrations of particular names or phrases from the play. For instance, the title of the album’s third track, “I Lost My Step in Nantucket,” quotes one of the drowned sailors whose voices fill the dream of Captain Cat after the opening monologue. As Tracey told the broadcaster Sue Lawley in a 1999 episode of Desert Island Discs: “It’s about a guy called Dancing Williams. And I tried to make the music reflect that name, Dancing Williams. Sort of a jaunty blues piece.” The thumping chord progression sounds for all the world as though Laurel and Hardy have dropped Stan’s piano down the stairs[1] – or perhaps I should say Peter Sellers’s Inspector Clouseau, since the riff itself is based on a quote from “The Pink Panther Theme.”

Elsewhere, Tracey supplies his own words, snippets of intralingual translation to give shape to the music. “Penpals,” the title of the Jazz Suite’s fifth track, can be assumed to refer to Mog Edwards and Myfanwy Price, who send ardent love letters back and forth across Llareggub. If we chose to hear the music as somehow conveying their correspondence, we could imagine Stan Tracey as composer, pianist, translator, and letter carrier rolled into one – a musical analog of Willy Nilly postman, whose wife “broods and bubbles over her coven of kettles on the hissing hot range always ready to steam open the mail” (UMW 25). The analogy is not entirely gratuitous: when Tracey was contemplating giving up jazz during a fallow period in the 1970s, his wife Jackie intercepted his application to become a postal worker…

And so I cycle back to where I began, to Peter Szendy and the question of signing, addressing, and sending one’s listenings. No doubt my reading of Szendy’s reflections on music and translation has been a tad cavalier, but in any case, I’ve tried to show what we can gain from stretching Stan Tracey’s own words to their logical limit and thinking about his music, his listening of Dylan Thomas, in translational terms. Simply put, the Jazz Suite behaves like a translation to the extent that it poses the question of Under Milk Wood’s translatability. If I can be permitted a final borrowing from Charlotte Mandell’s translation of Szendy, I would like to say that Tracey’s suite translates (an impression of) Dylan Thomas “in [Walter] Benjamin’s sense of translation, that of opening up a space of complementarity (better: of tension) among several languages” (L 68). Jean-Christophe Bailly, whose essay “La tâche du lecteur” [“The Task of the Reader”] is likewise a tip of the hat to Benjamin, alludes to “cette lecture traçante qu’est la traduction” (TL 27); I can see nothing for it but to propose as an English equivalent “the trace-y reading of translation” – and sign off.

Notes

[1] “All through the films that I’ve seen all my life, there have always been bits [where it] seemed to me: ‘Now this is a bit of poetry.’ … Just somebody coming down some murderous, dark, silent street, apart from the piano playing. Or it might have been a little moment when Laurel and Hardy were failing to get a piano up or down a flight of stairs.” Dylan Thomas, “Poetry and the Film: A Cinema 16 Symposium,” New York, October 28, 1953, in one of his final public appearances.

Works Retraced

Jean-Christophe Bailly, Saisir: Quatre aventures galloises, Paris, Seuil, 2018 (abbreviated as S).

––, “La tâche du lecteur,” in Panoramiques, Paris, Christian Bourgois, 2000 (abbreviated as TL).

Imogen Cassels, “Reading Closely with Your Voice: Under Milk Wood on the Radio, in the Afterlife,” Critical Quarterly, Volume 64, Issue 3, October 2022, pp. 61-79 (abbreviated as RC). See https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/criq.12654.

Duncan Heining, Trad Dads, Dirty Boppers and Free Fusioneers: British Jazz 1960-1975, Sheffield, Equinox, 2012 (abbreviated as TD).

Alyn Shipton, A New History of Jazz, revised and updated edition, New York, Continuum, 2007 (abbreviated as NHJ).

Peter Szendy, Listen: A History of Our Ears, translated by Charlotte Mandell, New York, Fordham University Press, 2008 (abbreviated as L).

Dylan Thomas, The Collected Letters, edited by Paul Ferris, 2nd edition, London, J. M. Dent, 2000 (abbreviated as CL).

––, Under Milk Wood: A Play for Voices [1954], edited by Walford Davies and Ralph Maud, New York, New Directions, 2013 (abbreviated as UMW).

Stan Tracey Quartet, Jazz Suite Inspired by Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood, Columbia, 1965.

Stan Tracey Quartet + Kenny Wheeler, Under Milk Wood in Hamburg [1966], Resteamed Records, 2022 (abbreviated as UMWH).

Translations from the French of Jean-Christophe Bailly are my own.

Samuel Martin teaches French at the University of Pennsylvania. He has translated works by several contemporary writers including Jean-Christophe Bailly and Georges Didi-Huberman; his translation of Didi-Huberman’s Bark was a co-winner of the French-American Foundation Translation Prize and was longlisted for the PEN Translation Prize.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, October 10, 2023