Introducing the Translation History in Global Perspective Series

by Claire Gilbert

The Translation History in Global Perspective series on Hopscotch Translation seeks to highlight an ongoing conversation between scholars working on the history of translation and translators for a broader audience. The series continues the discussion begun at a roundtable of the same name at the 2024 meeting of the American Historical Association and will feature contributions from participants in that roundtable and others. In this introductory essay, Claire Gilbert, one of the chairs of the roundtable, lays out some of the questions that have led historians to focus on issues of translation in recent years.

Who is the translator? From what positions–physical, political, intellectual, etc.–does this person do their work? What cultural conditions shape the possibilities for action and recognition by translators? What are the skills and support systems that make their work possible? What are the challenges and limitations faced by individuals and groups commissioned to make meaning across linguistic systems? How has the experience of translation differed across diverse spaces and times?

These questions are representative of themes which have motivated a recent trend across historical studies in different fields, and that we may call a social history of translation. Already in 1975, George Steiner made explicit that translation–as an embodied, and thus historically specific, process–was an integral part of all communication and meaning-making. In 1998, Lawrence Venuti identified the “Invisibility of the Translator” as a call to examine the person(s) and the context(s) which made translation work meaningful. In 2006 George Bastin and Paul Bandia affirmed the autonomy of a field of Translation History which looked beyond the text. By 2014, Jeremy Munday confirmed the interest across Translation Studies to incorporate “extratextual” materials into the study of translation in the past.

Meanwhile, historical study of mediation across languages has blossomed in recent decades as part of renewed interest in cross-cultural encounters. Historians, literary scholars, historical sociologists, and art historians have sought to define new approaches to the study of composite political institutions, cultural forms, and social relations which emphasize both multivalency and interpersonal interactions. Where such approaches are used to understand cross-cultural and multilingual encounters, scholars have drawn out a focus on the sites and the agents of translation. Renewed attention to both texts and contexts yields new insights into the daily practices and political stakes of translation activities as well as the historical specificity of translation history itself. In 2007, Peter Burke made an apt analogy, drawing on a well-used quotation from L.P. Hartley’s 1953 novel, The Go-Between, “If the past is a foreign country, it follows that even the most monoglot of historians is a translator.” Reflecting on this comparison, contributions to this series aim to bring historical and translation studies more fully into dialogue, together and with translation practitioners.

My own approaches to the study of translation in the past is conditioned by my work as an historian trained in social and cultural approaches, as well as linguistic and anthropological methods. For most of my academic career, I have been fascinated with questions about the intersections of language, power, and identity. These questions led me to focus on the interactions between diverse yet entangled language communities in the Western Mediterranean during the later Middle Ages and Renaissance, with a specific interest in those individuals who acted as translators. This research culminated in my book, In Good Faith: Arabic Translation and Translators in Early Modern Spain, where I explored the lives and practices of such individuals through the lens of “fiduciary translation.” Fiduciary translation, I argue, emerged in Early Modern Spain as a reflection of the political stakes, technical practices, and social sites inhabited by Arabic translators who navigated a perilous space between a demand for information from Arabic oral and textual traditions and increasingly punitive measures against Arabic speakers. This tension between demand for Arabic expertise via translation and limits imposed on Arabic knowledge grew just as innovations in language sciences and print technologies fostered an increasing connection between political subjecthood, religious identity, and language use. Such a fraught context increased a need for translation as well as the elaboration of codes of conduct and instruction manuals that would pave the way for greater institutionalization and professionalization for those working with and across languages.

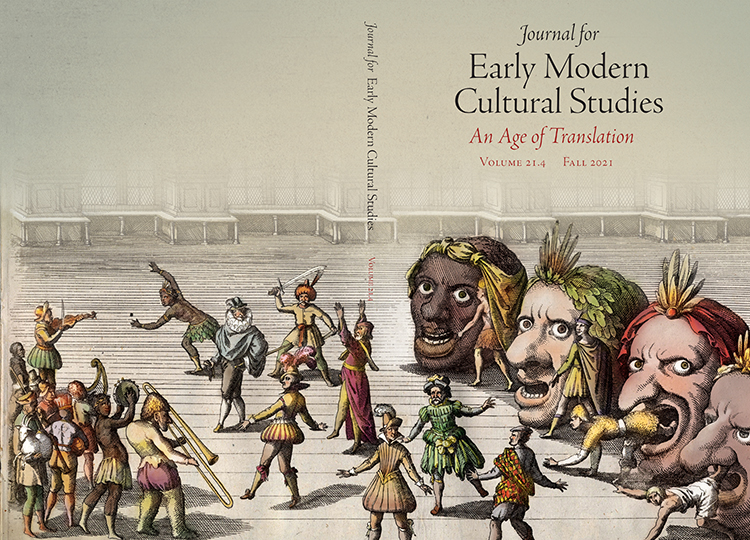

Though my book focused on Spain in a long sixteenth century, this project made me aware of the dynamic conversation about how translators shaped and were shaped by such political stakes and technical practices in a range of premodern contexts. It also brought me into contact–sometimes directly, sometimes through reading–with numerous scholars working on similar historical questions. A desire to understand this phenomenon collectively and through a comparative framework led me to organize a special issue of the Journal of Early Modern Cultural Studies which examined “An Age of Translation: Towards a Social History of Linguistic Agents in the Early Modern World.” The process of putting together this volume and its reception assured me of the strong interest in such topics among specialists and broader audiences.

Of course, mediation and multilingualism as phenomena are not limited to any particular historical period. Nevertheless, a good deal of recent scholarship has focused on translation, translators, and sites of multilingualism during the medieval and early modern periods (c.500–c.1800). Indeed, the increasing presence and professionalization of linguistic mediators, often working collaboratively through a range of oral and written modes, is well documented across the world from the twelfth century onwards. As Kapil Raj has argued, “cross-cultural mediation emerged as a specialized activity in its own right” during the second millennium CE.[1] By the nineteenth century, transregional exchange and migration fostered the definitive rise of professional cadres of linguistic specialists. What were the contributing factors to such a long boom in multilingual mediation? Who were the individuals whose lives and experiences made such a boom possible? Where did they do their work, find their livelihoods, and navigate their own complex identities?

Departing from these and other questions, a diverse group of scholars gathered at the Annual Meeting of the American Historical Association in January 2024. AHA President and Northwestern Professor Edward Muir and I brought scholars from a range of geographic and chronological focuses as well as distinct historical fields (literary, social, legal, religious, political) to explore translation as a process as well as a product, and to incorporate the human agency and contextual specificity which make each act of translation possible.

To this end, we asked our colleagues to respond to the following four questions:

- In the contexts in which you work, when and where do you see translation emerge as a discrete practice that is professionalized and/or institutionalized? Are there opportunities to trace translation work outside of professional and institutional contexts?

- Are there modes of (mis)communication and (mis)representation that accompany the translation activities you study?

- To what extent is it useful to distinguish between process and product when talking about the history of translation?

- What questions might you have for colleagues working on similar themes but different contexts and how might such questions help us to think broadly and/or comparatively about translation in the premodern world?

In response to these questions, colleagues invoked fascinating examples drawn from their archival research and careful analysis of historical texts. Common themes emerged around the probative value of translation in legal and administrative settings, the representational use of translation in royal courts or international diplomacy, the entanglement of translation projects and experiences of religious conversion, and the performance of translation as constitutive to individual and community identity, to name but a few of the engaging topics. Questions of method, terminology, and the ethics of both translation and historical inquiry were also raised. We were joined by an active audience of fellow scholars and translation enthusiasts who contributed ideas and examples from their own projects.

Based on the successful reception of the AHA roundtable, this new series at Hopscotch Translation aims to continue this discussion and bring it to a wider audience. We will initiate this forum with contributions from the original roundtable participants, but we hope to incorporate additional contributions from colleagues who were not able to join us in San Francisco, as well as others whose work intersects with this diverse and ongoing initiative to expand the historical study of translation. Along the way, we hope to engage new audiences and learn from them.

NOTES

[1] Kapil Raj, “Mapping Knowledge Go-Betweens in Calcutta, 1770-1820,” in Simon Schaffer, Lissa Roberts, Kapil Raj & James Delbourgo (eds), The Brokered World: Go-Betweens and Global Intelligence, 1770-1820, Sagamore Beach, MA: Science History Publications, 2009 pp. 105-150.

Claire Gilbert is associate professor of history at Saint Louis University. Her book In Good Faith: Arabic Translation and Translators in Early Modern Spain was published by University of Pennsylvania Press in 2020.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, May 14, 2024