Translating Power: Linguistic Domination in the Sicilian Court

by Joshua C. Birk

The creation of these documents was, in itself, an act of translation.

The Translation History in Global Perspective series on Hopscotch Translation seeks to highlight an ongoing conversation between scholars working on the history of translation and translators for a broader audience. The series continues the discussion begun at a roundtable of the same name at the 2024 meeting of the American Historical Association and will feature contributions from participants in that roundtable and others. In this third essay in the series, Joshua C. Birk introduces us to the multilingual politics of 12th-century Sicily.

As a graduate student, my interest was drawn to medieval Sicily because of its multilingual and multicultural environment. The concept of a twelfth-century Latin Christian ruler employing a Greek Christian chief advisor to create a royal bureaucracy, modeled after Islamic polities of North Africa and staffed, at least in part, by large numbers of Muslims and crypto-Muslims, challenged the narratives I had received about the modes of interactions of these groups throughout the medieval Mediterranean. Digging into the sources revealed the centrality of translation to understanding the nuances of governance, culture, and history in medieval Sicily. Scholars have had to use a small handful of surviving administrative documents, mostly land grants and privileges given to religious institutions, to reconstruct the fiscal administration of medieval Sicily. The notaries who composed these documents were generally capable of working in multiple languages. They often relied on translations, either oral testimony or previous records, in composing documents, and they then translated the final output of their work into multiple languages. These agents of translation highlighted the historical and cultural interactions that fascinated me, and exploring their processes of translation revealed the complexities and nuances of those interactions.

On the surface, the history of Sicily in the High Middle Ages appears to be the story of the triumph of Latin culture, and the subordination and eventual elimination of the Greek and Muslim cultures of the island. In the early eleventh century, the island had a roughly even population of Greek Christians and Muslims. Norman warriors, Latin Christians from the north of the Kingdom of France, who had established bases of power in Southern Italy, invaded the island in 1061, originally in collaboration with a disaffected Muslim governor, but quickly seized power independently. By 1091 they had conquered the whole of the island, ushering in waves of immigration of Latin Christians, primarily from the Southern Italian mainland. Throughout this process, the population of Sicily remained multilingual, and even when individual communities often lived within linguistic silos, the administration needed to work across all of these languages, making translation a central part of administrative practice.

Over the twelfth and thirteenth centuries acculturation, emigration, and conversion gradually eroded the Greek Christian population of the island. The Muslim population suffered a more cataclysmic fate. The Norman rulers of Sicily claimed dominion over the island’s Muslims, protecting them in exchange for particular obligations of service and the payment of specific taxes. The submission and service of these Muslims became a powerful symbol of the Sicilian monarchy in the twelfth century. However, they also became the target of resentment for Latin Christian immigrants, who often voiced discontent and anger with their monarchs through acts of mob violence against these Muslims. When a dynastic crisis enveloped the Sicilian monarchy in the 1190s and early 1200s, Latin Christian mobs forced Sicilian Muslims to flee from the urban settlements across the island and established independent enclaves in the mountainous hinterlands of Sicily.

In the 1220s, Frederick II reestablished the power of the Sicilian monarchy and violently asserted his authority over these Sicilian Muslim communities. He relocated the Muslims of Sicily to the mainland southern Italian city of Lucera, where he could better control and protect his Muslim subjects. There he reestablished the tradition of service and financial exactions that Muslim subjects had long rendered to the Sicilian monarch, and the Muslims of Lucera served as potent and visible symbols of Frederick’s power. Frederick II famously surrounded himself with Muslim attendants and reportedly spoke both Arabic and Greek. The papacy worked to undermine the power of Frederick and his descendants, eventually aligning with Charles of Anjou, brother of the French King, to conquer Southern Italy and Sicily in 1266. These new Angevine rulers would eventually decide that the costs of maintaining a Muslim population within a Christian Kingdom outweighed the benefits and depopulated the enclave of Lucera in 1300, selling the individual members of that community into slavery and scattering them across Latin Christian Europe. The destruction of Sicily’s Muslim population was complete. Yet, the habits of multilingualism and translation left indelible marks on the Sicilian language and the political and social history of the island.

It is tempting to view the Latin destruction of the Greek and Muslim cultures of Sicily as a teleological process, with every moment since the Norman arrival on the island in 1061 moving us inexorably closer to the destruction of these subordinated populations. In my research in The Norman Kings of Sicily and the Rise of Anti-Islamic Critique: Baptized Sultans, I have worked to complicate these ideas. The destruction of Sicily’s Muslim communities was not an inevitable result of the creation of a Christian polity on the island. The virulent anti-Islamic sentiments that arose in Sicily were inflamed by the decisions of specific historical actors at particularly historical moments. Examining the processes of translation or the work of agents of translation in twelfth-century Sicily reveals a more nuanced picture of the intersections of the island’s Greek, Latin, and Muslim cultures, and the process of studying these translation efforts allows us to recover these nuances.

In what follows, I want to illustrate how rulers and administrators in twelfth-century Sicily experimented with the institutionalization of translation programs within the royal chancery to define the identity and project the authority of the newly created Kingdom of Sicily and how these efforts complicate the picture of Latin domination. In the early eleventh century, the island had a roughly even balance of Arabic and Greek speakers. When Norman warlords from Southern Italy invaded the island in the latter half of the eleventh century, they brought with them French, the language spoken in court, and Latin, the language of their administrative and intellectual culture. Initially, these warlords forged ad hoc relationships with translators to help them navigate Sicily’s complex linguistic terrain. As they formed a cohesive polity, they initially created an administration primarily staffed by multi-lingual Greek Christians. In the 12th century, this administration shifted to include Latin Christians, Greek Christians, and Muslim notaries. These court notaries communicated the messages of Sicilian rulers to diverse audiences on the island, to their holdings on the Italian mainland, and populations across the Mediterranean world through various forms of public writing, often translating the words and symbols between their diverse cultural constituencies. Two programs of translation, one administrative and the other intellectual, illustrate the importance the twelfth-century court placed on translation and the development of professional institutions for translators. Historians have frequently studied these two translation projects in isolation, even though many of the same administrators were involved in both programs. Looking at them together illustrates the way the Arabic linguistic traditions of the island persisted, and even expanded, under Latin Christian rulers.

The first, and more enduring, of these translation programs centered on land use documents issued by the royal chancery, or dīwān, throughout the twelfth century (Metcalfe 2009, Johns 2002). Administrators of the Sicilian chancery sought to model their practices on those of Muslim polities, specifically those of Fatimid Egypt. The Sicilian chancery produced a series of daftar, boundary registers that outlined the specific borders of a territory. The creation of these documents was, in itself, an act of translation. Royal officials composed these documents by consulting previous registers (usually in Arabic) and conducting interviews with residents of the territory (in Greek or Arabic or a vernacular Latin/proto-Italian). The notaries would then translate these sources to produce a daftar in Arabic for the court. They would also issue a copy of the boundaries to the landholder. These would duplicate the Arabic text of the daftar, and then translate that text into either Greek, in the early twelfth century, or Latin, as that language became increasingly ascendant within the court in the second half of the twelfth century.

The dīwān not only documented the boundaries of land holdings of various estates but also drafted lists of the inhabitants of those same territories. Royal officials produced documents known as jarā’id, name lists of heads of households of the unfree population living on a particular piece of territory. Like the boundary registers, the creation of these documents required chancery officials to translate a range of sources across various languages. In some cases, landlords would submit lists of these people to the dīwān, usually in Latin, and then the chancery officials would conduct interviews with the heads of households of the territory. These agents would then produce the name lists in Greek and Arabic.

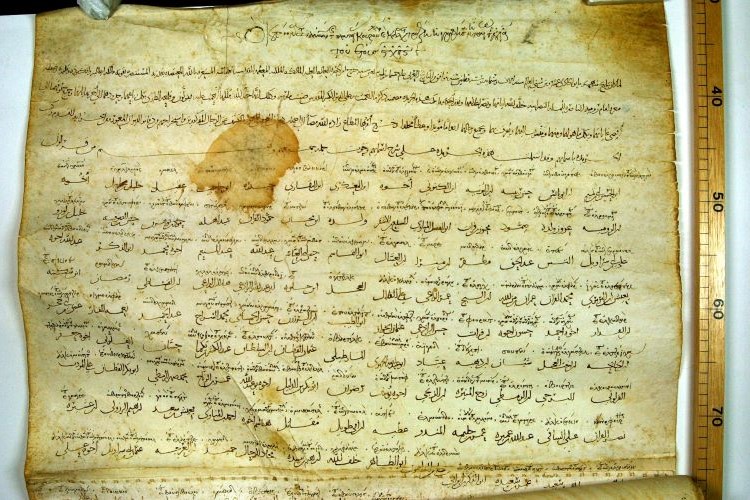

A jarā’id issued in by William II in 1178, of the Muslims living on lands granted to the church of Monreale. Palermo, Biblioteca Centrale della Regione Siciliana, Tabulario di S. Maria Nuova di Monreale, Pergamene no. 22.

A jarā’id issued in by William II in 1182, of the Muslims living on lands granted to the church of Monreale. Palermo, Biblioteca Centrale della Regione Siciliana, Tabulario di S. Maria Nuova di Monreale, Pergamene no. 45.

Though we have numerous documents produced by these offices, historians have been forced to recreate the translation process and procedures of these royal agents (Johns 2002, 193-213). We have no extant texts detailing the process of translation within the court, nor any explicit indication that such a text ever existed. We don’t know about the process for training these royal officials and the documents themselves frequently fail to identify the specific notaries who composed them. When we can identify the notaries involved in the production of these documents, they are often the product not of a single notary, but of multiple authors. Despite the multilingual talents of chancery officials, one scribe often composed the Arabic text, while another translated that text into the second language. The decisions made in translation and transliteration seem highly variable and idiosyncratic, but historians have identified some elements of a common translation strategy within the chancery (Metcalfe 2003, 127-140). For instance, the documents reveal a tendency to transliterate specific administrative terms and toponyms, that seemed to have crossed the linguistic barriers of the island (Martino 2019). These transliterated terms either reflected or became part of the spoken vernacular of Sicily for centuries after the end of these administrative practices. These specific practices not only help us better understand twelfth-century Sicily, but also invite comparisons to translation practices in other times and places. To what extent was translation a collaborative enterprise? When does transliteration become a preferred practice to translation? How do administrative chancery practices shape vernacular traditions?

These translated documents embodied the authority of the emergent monarchy and the way they used the Greek and Arabic-speaking agents of translation to shape royal power. Only the chancery of the crown employed trained agents with the linguistic capacities required both to gather the information contained in these documents and to draft the documents themselves. The dīwān then issued these documents primarily to the Italo/Norman nobility and clergy of the island, who often lacked the linguistic ability to read these texts, either in part or in whole. The importance of these documents was as much symbolic as practical. These landholders could not make practical use of these documents without a translator, but they served as symbols that the crown recognized their dominion over their territories and the agrarian workers who resided there.

A second translation program revolved around the translation of classical texts into Latin—and unlike the first, which continued throughout the twelfth century, this only occurred during a brief period lasting from 1156 to 1162. Previously, under Roger II, the Sicilian court had served as a patron for scholars and artists to produce new artistic and intellectual texts. But these works operated within narrow linguistic silos. (Miller, 2019) The most famous of these was the Book of Roger, a sweeping Arabic geographical text, composed by Muhammad al-Idris. The text spread throughout the Arabic-speaking world but was not translated into Latin until the seventeenth century, nor do we have any evidence of Latin Christians engaging with the contents of the text before then. Still, Roger II’s court commissioned a physical representation of al-Idris’ map, engraved on a silver disk with oceans of quicksilver. The Book of Roger paralleled the dafātir and jarā’id. For Arabic speakers within the administration, the text held technical value, particularly in its detailed descriptions of Mediterranean coastlines. But for Latin Christians, the text had symbolic value, removed from any ability to interact with the content of the text—and this typified intellectual production under Roger II. For Roger II, cultural production across a range of languages highlighted his power as a ruler and cultural patron for a vast panoply of diverse peoples who acknowledged his sovereignty. It was not necessary that these Arabic works be translated into French or Latin, their mere existence testified to the breadth of Sicilian royal power. For the scholars and poets who composed these works, Roger’s patronage validated both the existence of their communities, and their service to a lord, who, though Christian, valued Muslim cultural production.

In 1156, this administration of the court shifted its focus to the production of Latin translations of classical texts. In six years, the same royal administrators who oversaw the royal dīwān also produced a shockingly impressive volume of Latin translations of classical texts, including Plato’s Phaedo and Meno, Ptolemy’s Optics and Almagest, Euclid’s Data, Aristoteles’s Meteora, Proclus’ De Motu, The Fable of Kalila and Dimna, and the Prophecy of the Erythraean Sibyl (Molinini, 2009, Carlini 2007). Administrators translated these texts from Greek or Arabic into Latin, many for the first time. These translations fueled the production of commentaries from the medical school in Salerno and moved within the Sicilian court, but most of them never enjoyed the breadth and circulation of texts coming out of the more famous centers of translations in the medieval Mediterranean.

What accounts for the rapid emergence, and the just as swift disappearance, of this new program of translations within the Sicilian court? Explanations have often focused on the interests of the ruler. William I, a new king facing questions of legitimacy, sponsored these translations to buttress his position by projecting an image as a patron of scholarship and learning, while simultaneously connecting himself to a classical legacy of the island. But I want to return my focus to the administrators who oversaw and executed these translations, some of the same officials who worked in the palace chancery supervising the production of administrative documents discussed in the first translation program.

For the first half of the twelfth century, Greek Christians led the administration, most famously the amīr of amīrs, George of Antioch. George crafted an institution to staff the royal chancery and produced his eventual successors, a program of royal eunuchs within the court. These eunuchs, born into Muslim communities in North Africa, were captured, enslaved, castrated, converted to Christianity, and then trained as notaries carrying out translation tasks for the Sicilian crown (Birk, 173-195). George arranged for his protege, the eunuch of Philip of Mahdiya, to lead the administration after his death. But unknown enemies of Philip conspired to charge him with apostasy, for which he was executed, along with other palace eunuchs in 1153 (Birk, 139-171).

This second translation program was an act of linguistic domination, meant to mark the ascendancy of Latin officials within the royal chancery (Angold 2020, Molinini 1970). The translation movement was a one-way affair, laying claim to the intellectual heritage of the Greek and Arabic world, and bringing it into the Latin Corpus. This translation program seems to be the project of a small handful of Latin officials who enjoyed the king’s favor in the mid-1250s. The leader of this cohort was Maio of Bari, who enjoyed King William’s favor and used it to become head of the royal chancery in 1154, the first Latin Christian to hold that position. Maio launched this translation program both to elevate the status of his King and patron William I and to glorify the ascendance of Latin within the chancery. One of his chief collaborators in the project, Henry Aristippus, the archdeacon of Catania and the author of the Platonic and Aristotelean translations, would eventually succeed him. The translation program served as a both showcase for the political dominance of a Latin Christian kingdom, and a vehicle for laying claim to the intellectual products of Greek and Arabic texts.

But the brevity of these translation movements illustrates the complexity of this historical moment and cautions us against viewing it through the lens of the inevitable triumph of Latin Christian culture over Sicily. The unstable political careers of Maio and Henry imperiled their translation program. The nobility of the Kingdom resented Maio’s rise to power, leading to Maio’s assassination in 1160. Henry Aristippus continued much of Maio’s work but did not enjoy the same support from William I. In 1162 William I believed Henry was disloyal and ordered his imprisonment. Issues of translations played a central role in the accusations against Henry, who was condemned, at least in part, for his inability to manage the Arabic records of the dīwān, which continued to play a central role, both symbolically and administratively, for the King of Sicily.

King William I ultimately saw these second intellectual translation programs as secondary to the primary administrative work of the chancery. This second program, focused on establishing Latin Christian cultural dominance, never became institutionalized, and died with Henry, as neither subsequent rulers nor administrators sought to revive it. The experimentation with, and abandonment of this program of translation, coupled with the persistence of the multilingual productions of the royal dīwān, demonstrates the complexity of assessing narratives of Latin cultural ascendance. Focusing on translation practices therefore allows us to grasp complex linguistic vicissitudes that we might otherwise have missed. They help us understand the unique linguistic environment of Medieval Sicily, but also create the potential for comparative study by those interested in the process of translation in different places and times. They reveal medieval Sicily as a place that challenges perceptions about interactions between Latin, Arabic and Greek Speakers, but also allows us to more fully comprehend the complex reality underpinning the tragic destruction of the Sicilian Muslim community.

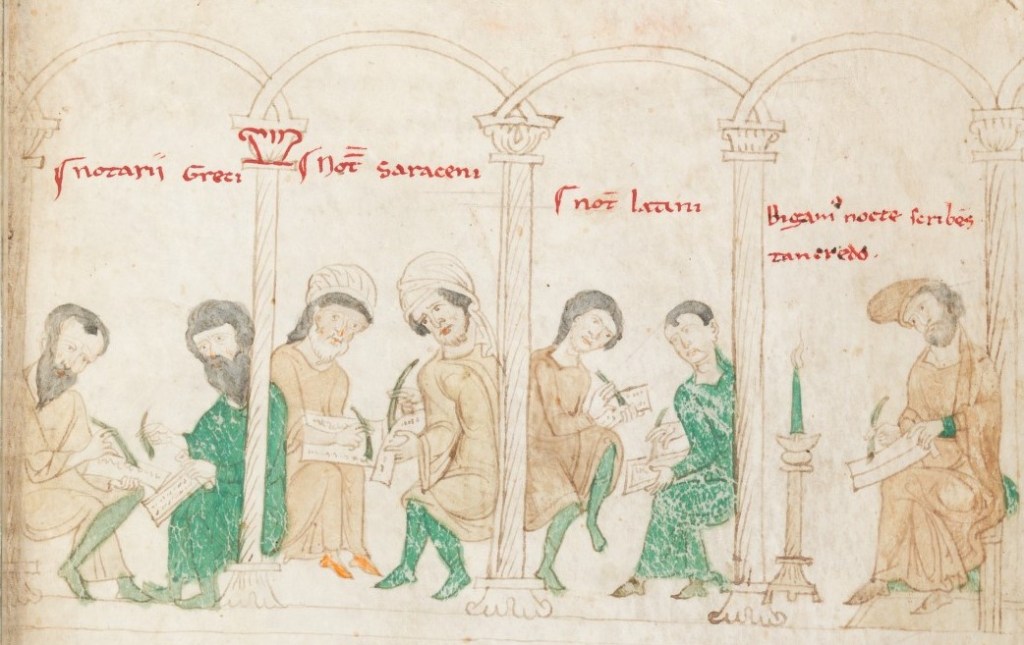

An image of the Greek, Muslim, and Latin notaries in the royal court of Palermo, from Peter of Eboli,

Liber ad honorem Augusti sive de rebus Siculis, Bern, Burgerbibliothek, Cod. 120 II, fo. 101r.

Works Cited

Angold, Michael. “The Norman Sicilian Court as a Centre for the Translation of Classical Texts.” Mediterranean Historical Review 35, no. 2 (July 2, 2020): 147–67.

Birk, Joshua. The Norman Kings of Sicily and the Rise of Anti-Islamic Critique: Baptized Sultans (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016)

Carlini, Antonio. “Vigilia greca normanna: il Platone di Enrico Aristippo.” In Petrarcha e il mondo greco, eds. M. Feo, V. Fera, P. Magna, and A. Rollo (Florence: Le Lettere, 2007)

Johns, Jeremy. Arabic Administration in Norman Sicily: The Royal Diwān (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002)

Martino, Paolo. “‘Contrata dicta in lingua latina Scandali, in lingua greca Chandachi, et in lingua saracenica Alcastani’. Playing with Identities in the Multilingual Place–names of Medieval Sicily” in Language and Identity in Multilingual Mediterranean Settings: Challenges for Historical Sociolinguistics. ed. Piera Molinelli. De Gruyter, 2017.

Metcalfe, Alex. The Muslims of Medieval Italy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009)

Metcalfe, Alex. Muslims and Christians in Norman Sicily: Arabic Speakers and the End of Islam, Culture and Civilization in the Middle East (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003)

Molinini, Daniele. “The First Sicilian School of Translators.” Nova Tellus 27, no. 1 (2009).

Miller, Nathaniel A. “Muslim Poets under a Christian King: An Intertextual Reevaluation of Sicilian Arabic Literature under Roger II (1112–54) (Part I).” Mediterranean Studies 27, no. 2 (2019): 182–209.

Joshua Birk is an Associate Professor of History at Smith College, who specializes in political history and cultural history across religious boundaries in the medieval Mediterranean world. He also serves as director of the newly Smith’s Humanities and Social Science Research Labs.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, July 23, 2024