Mumbo Jumbo, Verbal Acrobatics, Fun: On Translation As Reading

by Barbara Thimm

“There is amateurishness, and not-knowing, improvisation and instruction, as well as the reach for specialist knowledge.” – Kate Briggs, This Little Art

I am taken with Kate Briggs’ description of the translation process because I recognize the elements of the process that make it so immersive. There is no posturing, no hand-wringing at the impossibility of the perfect translation, but a kind of sensitivity for the deeply personal and tentative experience that the translation of a literary text entails. When I read a literary text, a literary text that I am about to translate, I must do so with what Buddhists might call “a beginner’s mind.” I must be open to the possibility that my first or my second understanding will be incomplete, not necessarily because I don’t understand the words on the page – but because I have only read them once or twice and I haven’t translated them yet. A lot of my work as a translator is in listening to the text, in trying one thing or another, in considering multiple meanings for the word on the page, and in weighing the literal meaning of a word against what I think works well in the text that is emerging on the page: the translation. Briggs’ description captures this tentativeness and humility – and the joy of discovery in this absorbing errand.

In the following, I will connect my experience as a teacher and translator to my interest in conceptualizing translation as a reading and writing practice. Translation is a valuable process in its own right, not merely a necessary step toward the end product, the written translation.

My thinking is informed by the work of Carl Bereiter and Marlene Scardamalia on The Psychology of Written Composition (1987), an extensive empirical study on writing behavior. Literary translation is a specific and demanding form of writing, a fact that is often overlooked in discussions that focus on defending the value of translation at best or at brandishing the reviewer’s foreign language skills at worst. I am particularly interested in Bereiter and Scardamalia’s conceptualization of two different models of composing: first, a “knowledge telling” model that assumes that writing is a relatively straightforward activity, and, second, a “knowledge transformation” model that views writing as “a task that keeps growing in complexity to match the growing competence of the writer.” A consequence of using the latter model is to account for the fact that “as skill increases, old difficulties tend to be replaced by new ones of a higher order.” This is true for translation as well.

Reading and Writing in the Translation Process

I write because I have read.

– Roland Barthes

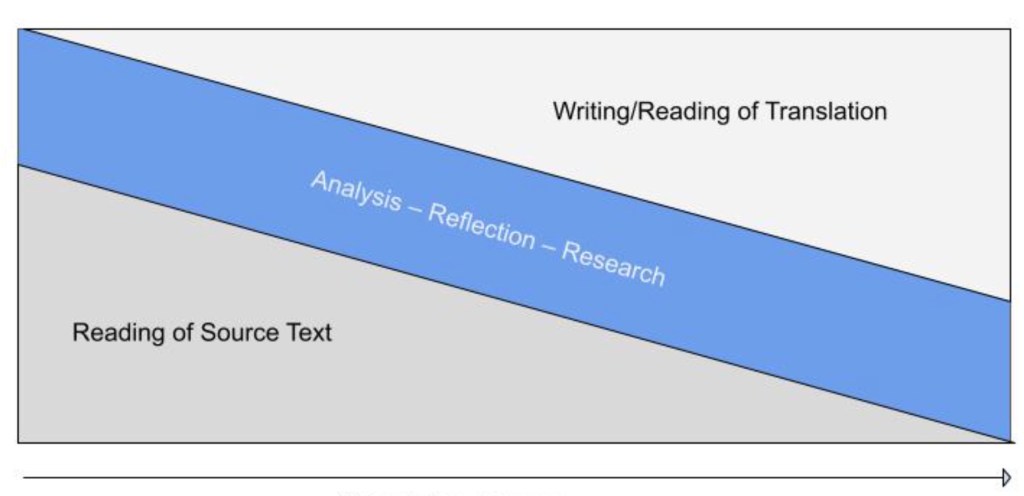

The image below shows a simplified conceptualization of three spaces that all translators inhabit during the course of a translation: the reading of the source text, the writing and reading of the translation as well as the space of reflection that accompanies these activities. The reading of the source text is the condition sine qua non of translation: there is no translation without a reading of the source text on whatever level that might be. Depending on the work under consideration, such reading of the source text is not straightforward or unambiguous, particularly in modern literature. The specific attention a translator brings to the source text is, in my opinion, an essential and at the same time a very personal component of a particular translator’s work. Reading for translation is not a receptive skill as it is already pervaded by the necessity of its iteration in another language.

Mark Polizzotti points out that “[l]anguage is not all about designation. Its real meanings often hover in the spaces between utterances, in the movement generated by particular arrangements of words, associations and hidden references. This is what literature does, in the best of cases.” (Sympathy for the Traitor, 2018) The translator’s specific and idiosyncratic reading is very much situated in her experience, her sensitivity to the particular movement of the source text and her predilections, all of which shape her understanding of the meanings in these “spaces between utterances” and her understanding of the meaning of the source text.

The writing and reading of successive translation drafts document the translator’s progressive understanding of the source text as well as her thinking experiments in the target language (see, for instance, Mara Faye Lethem’s essay on translation manuscripts or Sophie Hughes’ dazzling animation of the editing process in the New York Times).

Between the two is a space of largely invisible activity, lexical research, syntactical analysis, possibly cultural and academic enquiries, and “simple” thinking about both texts. Over time, the importance of reading the source text decreases, not because the source text becomes less important but because the translator is absorbing her reading of it into her translation.

A specific translator’s movement in these spaces may differ in response to characteristics of the translator, such as her experience, her prior reading, or her linguistic origin, and properties of the source text, such as the age of the source text or the availability of its author for consultation. Furthermore, there is what Karen Emmerich calls “textual instability,” the fact that there is rarely only one solid original. As a consequence, translation is often also an act of “interlingual editing” whether or not the translator ignores or engages with the text’s instability (Translation and the Making of Originals, 2017). A less experienced translator’s reading is likely to be simpler and more superficial, while a more experienced translator will pick up on nuances, ambiguities and allusions as she is translating. To quote Bereiter and Scardamalia’s concept of knowledge transformation again: “as skill increases, old difficulties tend to be replaced by new ones of a higher order.”

In the following, I begin by investigating two examples of student reflections on a single sentence in Walter Benjamin’s short autobiographical text “Steglitzer Ecke Genthiner” [“At the Corner of Steglitzer and Genthiner”]. These reflections are brief, and they constitute a relatively superficial reading of Benjamin’s sentence. Still, I believe that the difference between these two readings illuminates gradations in reading attention that fundamentally shape the translation process.

Two Readings

In a graduate course on literary translation I taught at the University of Frankfurt, one of the assignments towards the end of the class asked students to reflect on the translations they had done during the semester, to pick one sentence that had been particularly “difficult to translate” and to reflect on the sources of that difficulty. Two students chose the same sentence from Walter Benjamin’s “Steglitzer Ecke Genthiner.” For my purposes, it is less important to quote the sentence here or explicate the prompt’s pedagogical reasoning. Instead, I am interested in looking at these student responses to understand how early readings of the source text can differ.

One student, a native German speaker, writes:

“This sentence was difficult for me to translate because of the complexity and the length. For this reason, I translated the sentence word-for-word, hoping to then comprehend what the author is saying and finally translate the sentence into standard English. The content of the sentence is not linear and the author mixes verb tenses. In addition, the events within the sentence stem from the past and the present, this further adds to its complexity.”

It is notable that the student translated the sentence “word-for-word” with the objective of understanding “what the author is saying” in order to be able to translate it into “standard English.” It clearly shows the student’s understanding that translation can be used to effectively read a difficult text that had, in this case, been written in her first language. The student goes on to reflect on technical aspects of the source text, such as the mixing of verb tenses, but she stays on what I would call the “surface level” of the text. Difficulties of style and vocabulary are not mentioned, nor does she reflect on what the mixing of verb tenses might imply for the meaning and effect of the sentence.

If we look at translating as writing, we can say that the student is diligent in assuring that the technical elements of her task, word choice and grammar, are aligning to form a correct sentence (no matter whether or not the resulting sentence is, in fact, a “correct” translation). She is also aware that the meaning of the sentence she is translating is not easy to understand, even though we cannot be entirely sure what the effect of her “word-for-word” translation on her understanding will be.

The other student, a native Spanish speaker, writes:

“I found it extremely difficult to translate this sentence. Moreover, at the beginning, I didn’t comprehend the meaning. Just after asking a native German speaker, I was able to understand basically what the author wanted to say. The next problem was transferring the emotion of this passage. This passage is full of melancholy, but where? I decided to focus on the words that, in my opinion, transmit this sensation of melancholy: “…abgeschiedenen Flecken vorüber jagte…”, “…jener alten Mütterchen” and “vor Zeiten hinter sich gelassen haben”. [Slightly edited for clarity]

Like her classmate, this student acknowledges the difficulty of understanding what “the author wanted to say.” Still, she also understands that there’s more to the passage, a feeling she calls “melancholy,” which could also be called nostalgia, as Benjamin is writing about his childhood. While her reading remains superficial in some aspects — she does not consider the effect of syntax and rhythm, an essential element of this passage — she does name her emotional reaction to the sentence. In addition, she is aware of the need to reflect that in her translation.

These reflections point to elements of literary translation that concern reading a source text with the motivation to translate it. One is more sensitive than the other, but neither exhibits the complex problem-solving that literary translators associate with their task. However, the difference between these two reflections points to the complexity of reading a “difficult” (read “rich” or “literary”) foreign text.

Lexical Jamming in Ror Wolf’s Continuation of the Report

More complex problem-solving occurs in my translation of a German novel, Fortsetzung des Berichts [Continuation of the Report], by the German writer Ror Wolf (1932-2020). Although billed as a novel, Continuation of the Report is not a traditional narrative. Ror Wolf himself describes his project in “Meine Voraussetzungen” [My Premises, 1966]: “No whispered wisdoms; no ideologies one could approve of; no steaming meanings; no cultural tidbits for the readers perusing their material in search of them; no authoritative statements; no concepts on a large scale; no characters acting according to psychological principles; no moral; but: play, nonsense, mumbo jumbo, burlesque, verbal acrobatics, fun; fun that may, of course, turn into horror at every turn.” [my translation]

Continuation of the Report loosely follows two plotlines, although it could be better described as a collage of pictorial descriptions, language games, and grotesque storytelling vaguely tied together by said plotlines. The book’s playful aesthetic effect supersedes the narrative. Take, for instance, a sentence in the first half of the book where three characters offer competing motivations for one of the central events in the text, the killing of a cook. Here, Wolf uses series of unpunctuated words to create a kind of verbal image, a stylistic move that could be described as” lexical jamming”:

[GERMAN]

In einer Zeit, sagt Wobser, in der nur Fasriges Traniges Ranziges Holziges Strunkiges Modriges Korkiges Klitschiges Klebriges Klümpriges gegessen wurde, sei der Koch wie ein weiß aufgeschütteter Vorwurf dagewesen und habe von Gebackenem Gebratenem Geschmortem Geschmelztem Gesulznem Geselchtem Gekochtem Gerupftem Gehacktem Gefrorenem Gestürztem Gedünstetem Gewürztem Gespicktem Geriebenem Geschlagenem Gepreßtem Gerührtem gesprochen und habe es mit seinen blossen blassen Händen beschrieben und in der Vorstellung zubereitet abgeschmeckt angerichtet und aufgetragen und dann, wenn diese Vorstellung abgetragen worden sei, sei nur die haarige ledrige poröse Speise dieser Zeit zurückgeblieben, das sei, sagt Wobser, der Grund für die Tötung gewesen.

[ENGLISH; rough draft]

At a time, says Wobser, when one only ate food that was fibrous oily rancid stringy tough moldy corky slimy sticky clumpy, the cook had been there like a heaped-up white reproach, had talked about things baked roasted braised sautéd jellied cured boiled plucked ground frozen stewed smoked pickled toasted spiced larded grated whisked squeezed stirred, had conjured them with his pale bare hands and, in his imagination, had prepared seasoned dressed and served them, and then, when this spectacle was cleared away, all that was left was the hairy leathery spongy fare of that time, and that, says Wobser, had been the reason for the killing.

Wolf uses twenty-one words to illustrate the cook’s obsession with food preparation. This verbiage is presented in a tightly regulated uniform format as a series of past participles with identical beginnings and endings, due to their grammatical function in German. There is also assonance within the series, enough to suspect that the order of the list is not random. For instance, “Geschmort” and “Geschmelzt” are assonant, as are “Gebackenem” and “Gebratenem.” The list seems more than a series of items that mean something individually; instead, it should be recast as an aesthetic object. If I want to translate this effectively, I need to step back from the text and rearrange the list.

The following table formalizes my thinking.

The original German words are contained in the left column. These nouns are past participles of verbs that describe ways to prepare or conserve food. In German, nouns are capitalized; they all begin with “Ge-” because they are passive and end with “-em” because they are all declined as objects of the preceding verb. That is, the original gives us a list of twenty-one nouns that look and sound somewhat uniform even though they denote a diverse set of food preparation methods.

The second column lists “literal” English translations of the German words. Due to the nature of language and the fact that the English dictionary contains more words than German, a German word often has more than one possible English translation. I cannot recreate the alliteration at the beginning of the words nor do I think capitalization is an appropriate choice, as capitalization is much less common in English than in German. I also see several possible rhymes in my list in the second column that offer some opportunities for assonant play. The column to the right contains the rearranged list I came up with. My result is different from what Wolf has written; it is not a direct translation:

At a time, says Wobser, when one only ate food that was fibrous rancid tough moldy musty oily slimy stringy sticky clumpy, the cook had been there like a heaped-up white reproach, had talked about things baked boiled stewed stirred steamed sautéd simmered smoked salted sliced zested spiced chopped larded plucked pickled kippered whipped toasted roasted cured, had conjured them with his large bare hands and had, in his imagination, prepared seasoned dressed and served them, and when this spectacle was cleared away, all that was left was the hairy leathery spongy fare of that time; that, says Wobser, had been the reason for the killing.

I rearranged the list to create assonances, whether they were alliterations (like baked, boiled, stewed, stirred, steamed, etc), plosives (such as plucked, pickled, kippered, whipped), or rhymes (e.g. toasted, roasted). Creating the table above was a helpful strategy for laying out potential translations and considering different ways to express the original text in English. (It is certainly not the only possible approach. Lily Jumel, in her 1970 French translation of the book, remains closer to the original meanings and arrangement without aiming for phonetic resonance.)

Here is an instance of what Umberto Eco refers to as an “aesthetic effect” in “Translation and Interpretation” (Experiences in Translation, 2001) where he remarks that it “is not a physical or an emotional response, but an invitation to see how a particular physical or emotional response is caused by a particular form in a sort of continuous ‘shuttling’ back and forth between effect and cause.” The emotional response to Wolf’s verbal jamming in the above example is a feeling of excess. As such, it complements the content of the passage, in this case, the cook’s insensitivity to the context of his time. Eco continues: “[a]esthetic effect is not just a matter of the effect one experiences but also an appreciation of the textual strategy that produces it.” [my emphases] That is, my task as a reader of the text is to gauge my reaction to the text and to connect this reaction to Wolf’s textual strategy in German. As a translator, I have to formulate an appropriate strategy for the target language, English.

Lexical jamming is a distinctive feature of Wolf’s style in Continuation of the Report, although it is not always so prominent. Its primary effect is to foreground the materiality of language by creating a non-syntactical tapestry of morphologically similar words. As a native German speaker and translator, the translation of this text has given me a new appreciation not only for the richness and diversity of German but also for the common etymological roots of German and English.

Another early passage in Continuation of the Report lists seventy-two fish names that occur as punctuated and unpunctuated lists with occasional syntactical interjections. This passage, a three-page paragraph, requires a more elaborate strategy: research shows that most of the fish names are common names, likely chosen for their sound (“Spitzer Plinken Plinten Rapfen Mülpen Gösen”) and that some names refer to the same fish. A final pun, where the German name for the fish is “Koch,” the German word for “cook,” allowed me to find a research paper about the role of natural history in Continuation of the Report. According to Tanja van Hooren, Ror Wolf was sitting in a library next to a zoological encyclopedia when he wrote this passage, and he was picking fish names for their comic potential and sound (Naturgeschichte in der ästhetischen Moderne — Max Ernst, Ernst Jünger, Ror Wolf, W. G. Sebald; 2016). This example of a quasi-scientific lexical firework, Kate Briggs’ “reach for specialist knowledge,” can be challenging for the translator. It is also a fascinating diversion into the richness of literary practice.

Both of these examples illustrate how the demands of the target text, the translation, supersede the need for factual accuracy, and require the translator to engage with the possibilities of the target language. However, the series of fish names poses the more significant challenge, not only because the proper names in the source text have specific equivalents in English (apart from the even greater challenge of regional variations of fish names), but also because the use of proper names in a quasi-scientific way seems to demand a kind of accuracy at odds with its aesthetic dimension. It is the translator’s task to find a consistent textual strategy that balances zoological nomenclature and aesthetic effect.

I hope this exploration has illustrated the nuanced spaces a translator navigates throughout the translation process, where the simultaneous yet distinct readings of the source text and the emerging translation shape the translator’s approach. By examining two student reflections, I have illustrated how novice translators approach complex sentences: one focuses on using translation to comprehend the source text, while the other is alert to the sentence’s aesthetic impact. Furthermore, the analysis of lexical jamming in Wolf’s Continuation of the Report demonstrated a practical approach to dissecting specific textual strategies to recreate their aesthetic effects in translation. Literary translation is an important and still under-appreciated cultural practice not only for the literature it promotes but also in its own right.

Barbara Thimm is a writer, translator, and educator based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Two books with her translations of selected poems by Timothy Donnelly and Mary Jo Bang were published by luxbooks in Germany. “A Discovery Behind the House,” the translation of a short story by Ror Wolf, appeared in Asymptote. She is interested in the intersection of literacy and literature.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, September 10, 2024