Epic Translation in Early Modern India

by Audrey Truschke

Not everybody at the Mughal court supported translating Sanskrit texts into Persian...

The Translation History in Global Perspective series on Hopscotch Translation seeks to highlight an ongoing conversation between scholars working on the history of translation and translators for a broader audience. The series continues the discussion begun at a roundtable of the same name at the 2024 meeting of the American Historical Association and will feature contributions from participants in that roundtable and others. In this second essay in the series, Audrey Truschke introduces us to the early modern Mughal Empire’s project of translating Sanskrit texts into Persian.

Introduction

Between 1570 and 1660 CE, dozens of Sanskrit texts were translated into Persian in northern India under imperial Mughal patronage. This 90-year translation project was one of the largest knowledge transfers between literary cultures in early modern Asia. It coincided with the heyday of the Mughals (c. 1560–1720), who originally hailed from Central Asia and intermarried with Indian Rajputs. Mughal kings were Muslim, while their wives were of various religious backgrounds (including Hindus), and they presided over a diverse, land-based empire in northern and central India.

I have explored the linguistic and cultural features of Mughal translations—based largely on close readings of the Sanskrit originals alongside their Persian translations—in numerous prior publications (Truschke, Culture of Encounters, “Mughal Book of War,” “Padshah like Manu”, “Persian Text of the Doha Ramayana”). Here I offer a broader consideration of key structural and social aspects of Mughal-sponsored Persian translations of Sanskrit works, both to understand this intellectual endeavor’s contours and as an indication of what we might be attuned to notice about translation projects in other times and places. I argue that Sanskrit-to-Persian translations under Mughal patronage were, by design, collaborative, involved detractors, and always unfinished.

Epic Project

When the Mughals commenced their translation enterprise in the 1570s, Sanskrit and Persian were established Indian languages with different social positions and histories. Classical Sanskrit had thrived as a cosmopolitan language for nearly 1,500 years, widespread across the subcontinent but limited to rarified elites (Sanskrit was never a vernacular language) (Pollock, Language of the Gods). In contrast, Persian had doubled as a spoken vernacular and an elite medium, especially in northern India, since the early second millennium CE. Persian grew in reach and importance during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—concomitant with the translation project—owing to Mughal support (Alam). Indian intellectuals had translated works from Sanskrit into Persian in earlier centuries (Ernst), but never on a scale approaching that of the Mughal translation movement 1570–1660.

The Mughals’ translation agenda was wide-ranging—including dozens of direct translations alongside attempts to synthesize knowledge—and at its center stood the two gigantic Sanskrit epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. The Mahabharata is the longer of the two, stretching to seven times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined as it tells the story of a family struggle for the throne that drew the entire known world into a disastrous war (Doniger 249). The Ramayana centers on King Rama, who unjustly loses and later regains his kingdom and his wife. Both epics were constantly retold in premodern India, in countless versions and languages, by a range of regional and religious groups (including but not limited to Hindus). Among many admirers, premodern Indian kings were fans of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, finding political uses in adapting the epics’ imperial geography and in-built othering skills, respectively (Pollock, Language of the Gods chap. 6 and “Ramayana and Political Imagination in India”). By the time the Mughal Empire dawned in 1526, the two epics were critical components of the lexicon of Indian kingship, which helps to explain why the third Mughal king, Akbar (r. 1556–1605), assigned teams of translators to spend years rendering each Sanskrit epic into Persian prose (after which, the manuscripts were heavily illustrated). The Akbari Persian Ramayana has not been printed, a sign of the ongoing neglect of premodern India in the modern academy. Here, I draw on my work on manuscripts of the Ramayana translation, as well as the Tehran printed edition of the Mahabharata translation (renamed Razmnama in Persian, meaning “Book of War”) to identify broad features of the Mughal translation movement.

Collaborative Work

When the Mughals began translating texts from Sanskrit into Persian, nobody involved knew both languages. This required translators to work in pairs or, for the larger translations, teams of translators. Most commonly, the Persian-knowing translators were Mughal elites formally part of the status apparatus (and, often, the mansabdar system of ranked Mughal officials) and the Sanskrit-knowing translators were educated Brahmins or Jains (Hindu elites and a religious minority, respectively). Each pair or groups of translators communicated verbally via Hindi, a north Indian vernacular. As Naqib Khan, a Mughal historian and translator, explained in a colophon to the Razmnama:

I [Naqib Khan, son of Abdul Latif Husaini] translated [the Mahabharata] from Sanskrit into the Persian language in one and a half years. Some Brahmans, namely, Debi Misr, Satvadhani, Madsudhan Misr, Chaturbhuj and Shaikh Bhawan, who with His Majesty’s attention, has become honoured by having accepted Islam, read that book and explained it to this sinful author in Hindi, and the author wrote it down in Persian. (Haider 120–21, his translation)

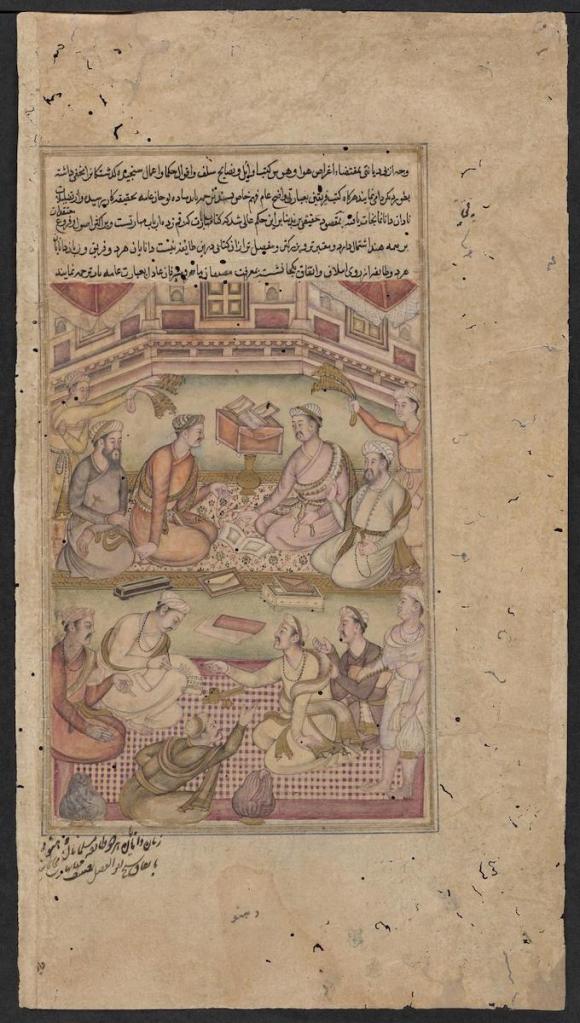

This oral transmission between two teams is visually attested in a manuscript illustration of the Razmnama’s preface that shows the Brahmin and Mughal translators conversing, with manuscripts strewn around each group (in an accurate detail, the Persian manuscripts are vertical in format, whereas the Sanskrit manuscripts are horizontal).

Razmnama Leaf, Mughal and Brahmin Scholars Translate the Mahabharata from Sanskrit into Persian, 1598–99, Free Library of Philadelphia, Lewis m18, public domain

The collaborative model of Mughal translation shaped the newly produced Persian texts in numerous ways. Traces of Hindi—the shared oral medium—are sprinkled throughout Mughal Persian translations. Most commonly, Sanskrit words and names came through with a vernacular pronunciation in Persian, such that Krishna (a Hindu god) became Kishan, the hero Rama morphed into Ram, and so forth. When applied to thousands of names and retained Sanskrit words (another feature of the Razmnama and other works), this gives rise to a noticeable Hindi vernacular tone in Mughal Persian translations. Sometimes, traces of conversation and verbal commentary are also retained in the newly-created Persian texts, including glosses on the story and the occasional line of Hindi poetry.

Some Mughal translators recorded, as part of the epic story, the act of the Sanskrit translators narrating the saga in Hindi. This comes across, for instance, in the Razmnama where narrating the Mahabharata epic at the Mughal court is incorporated into the translation as a frame story. When one reads the Persian text, you can never forget the act of collaborative translation since every book (there are eighteen books in total) begins with “Then the Indian storytellers relayed…” or “Then the Brahmins told us…” (Razmnama). This roots the translation in a particular time and place—namely the late sixteenth-century Mughal court of Emperor Akbar in which Brahmin and Mughal translators gathered—even long after that moment and collaboration became part of history.

Reluctant Translators

Not everybody at the Mughal court supported translating Sanskrit texts into Persian. The points of opposition help us to identify the cultural stakes of individual translated texts as well as the implications of the knowledge transfer project more generally in early modern India.

On the Sanskrit side, arguably all the Brahmin translators evinced some reluctance to engage, or at least advertise their engagement, with Mughal translation projects. Brahmins never wrote about their translation activities in Sanskrit sources so far as modern scholars have been able to recover (we know of their involvement from Mughal Persian texts). It is hard to discern what fueled Brahminical silence, but likely relevant were the prescriptive declarations of Brahmin Sanskrit intellectuals since the first millennium CE that there were only four literary languages: Sanskrit and three Sanskrit-derived languages known as Prakrits (Pollock, Language of the Gods chap. 2). In contrast, Persian was “like the cry of wild birds” as per the twelfth-century Sanskrit poet Jayanaka (10.45) and more grating than the “screeching of owls” as per the fourteenth-century Sanskrit poet Gangadevi (8.12). Against such cultural rejection of Persian and its aesthetic possibilities, what would it mean for a Brahmin Sanskrit intellectual to help produce a Persian translation? Certainly, they would face objections to any claim, at least made within the Sanskrit realm, to be creating literature. Indeed, non-Mughal affiliated Brahmins of the period, like Khandadeva, cautioned against Sanskrit intellectuals becoming bilingual (dvaibhashika), a general warning against involvement in Indo-Persian culture (Pollock, “Languages of Science” 34). Clearly, many went against this proscription in practice, instead electing to help expand the boundaries of Persian literature. But Brahmins still struggled to find a way to articulate, at least to their intellectual peers, the merits of a liberal approach to cross-cultural exchanges and knowledge sharing.

On the Persian side, Badauni is the best example of a reluctant translator, and his objection was partly rooted in religious difference, rather than literary norms. Badauni was a curmudgeonly courtier who followed a more conservative interpretation of Islam than was in vogue in Mughal elite contexts. In his acerbic history of the period, he demeaned the translation work that Akbar ordered him to complete, saying that he worked against his will and under the compulsion of royal command. Badauni suggested that translating the Ramayana, especially, compromised him as a Muslim, pleading with his readers—or perhaps, really, with himself—that “narrating heresy is not itself heresy” (naql-i kufr kufr nist) (Badauni 2:366). Indeed, part of Emperor Akbar’s goal in sponsoring translations of Sanskrit texts into Persian was to challenge conservative Muslims. For example, in his preface to the Razmnama translation, Abul Fazl (Akbar’s vizier) noted that the Persian translation of the Mahabharata should cause conservative Muslims to “abandon their distasteful belief” that the earth was only 7,000 years old (Akbar thought it was far older; Razmnama 1:xix and translated in Ernst 180–82; for a full translation of the preface, see Kovacs). Perhaps Badauni was among the first Mughal targets for this intervention.

Badauni disliked Akbar, the king for whom we worked, and so it is impossible to distinguish his disdain for Akbar’s translations from his disdain for Akbar. In this, we might see a criticism of Mughal kingship, perhaps especially the Mughal investment in older Indian ways of projecting sovereignty. In this regard, Badauni’s opposition highlights that even an intellectually liberal project—such as translating Sanskrit texts and knowledge into Persian—served to concentrate royal authority in Mughal India, which was anything but a liberal political agenda.

Unfinished Translation

Indo-Persian intellectuals seemed to view Mughal Persian translations of Sanskrit texts as a perennially incomplete project, and they repeatedly returned to key texts—especially the two epics—for retranslation. This began with the Mughals. Akbar’s poet laureate, Fayzi, rewrote the first two books of the Persian Razmnama (which were in prose), infusing them with his own poetry (Fayzi’s rewriting remains unprinted but survives in numerous manuscripts). Later generations of Mughals retranslated parts of the epics from Sanskrit anew, such as the Bhagavadgita (a philosophical section of the Mahabharata that the Mughals largely cut from the Akbar-period Razmnama). Also, the Mughals lavishly illustrated both translated epics, which furthered the translation’s political agenda by, for example, visibly identifying Akbar with King Ram (Adamjee and Truschke). Taking these cases collectively, we see how the Indian epics, once part of the Persian literary world, were reworked to promote literary, philosophical and political agendas, not all of which were key impulses behind the initial formulation of this translation movement.

In later decades, especially post-1660, Indo-Persian authors beyond the Mughal court returned to the epics. Between the late sixteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Indian writers produced at least two dozen distinct Persian Ramayanas and fresh translations of multiple books of the Mahabharata (including books 4, 5, and 14). In some cases, the authors-cum-translators dedicated their Persian works to the reigning Mughal king, signaling an enduring cultural association of the Mughals and Sanskrit stories. The Persian Ramayanas are a remarkably diverse collection, ranging from Persian masnavis (book length poems) to prose works; in terms of focus, too, they differ with some presenting a hero’s tale of war while others offer a love saga between Rama and Sita (Mujtabai 68–71). We often do not know if an author accessed the Ramayana story via the Sanskrit epic, a Hindi retelling, a mediated version of either, or other Persian Ramayanas. Above all, in this range of recastings, we see how the Ramayana became an integral part of Indo-Persian literature, as worthy of constant retelling as the older Persian stories of Layla and Majnun, and Khusraw and Shirin.

During the seventeenth century, the predominant audience for Mughal translations shifted from Muslims to Hindus, and, following this change, a distinct form of rewriting the Persian versions of epic Sanskrit works flourished in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Mughals envisioned themselves as the main audience for their translations, evidenced by producing imperial manuscripts and comments in histories and prefaces. For example, Akbar recommended the Razmnama to one of his sons as edifying reading for a potential future king (Moosvi 94). But, from the late sixteenth century onward, many Hindus learned Persian to work for the Mughal state and to participate in this flourishing Indian literary culture. By around 1700, more Hindus could probably read Persian than Sanskrit. Most Persian manuscripts of the translated epics date from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and many were written by Hindu scribes who sometimes inserted honorifics for Hindu gods (e.g., Shri Kishan Ji, as opposed to just Kishan, i.e., Krishna). More rarely, Hindu scribes or readers wrote out deity and character names in Devanagari script, associated with Sanskrit in much of northern India, thereby enhancing the Hindi tone of the Persian text already apparent in linguistic forms (see above). These interventions changed the tenor of the translations, transforming them (perhaps restoring the epics, for some) to devotional Hindu works.

Conclusion: Untimely End

The Mughal translation project and its aftereffects halted as a major dynamic in India when Persian ceased to be used as an Indian literary and vernacular language in the nineteenth century. Numerous larger forces brought about the end to this premodern cosmopolitan literary tradition (Guha), but I do not think that translation was among the causes. On the contrary, translations of Sanskrit texts enlivened and deepened the Persian tradition in India and presumably would have continued to do so, if modernity had not intervened. In all likelihood, the Mughal translation movement—especially the epics at its center—would never have been conclusively completed.

Works Cited

Adamjee, Qamar and Audrey Truschke. “Reimagining the ‘Idol Temple of Hindustan’: Textual and Visual Translation of Sanskrit Texts in Mughal India.” In Pearls on a String: Artists, Patrons, and Poets at the Great Islamic Courts, edited by Amy Landau, University of Washington Press, 2015, pp. 141–65.

Alam, Muzaffar. The Languages of Political Islam: India 1200–1800. University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Badauni. Muntakhab al-Tavarikh. Edited by W. N. Lees and Munshi Ahmad Ali, vol. 2, College Press, 1865.

Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History. Penguin, 2009.

Ernst, Carl. “Muslim Studies of Hinduism? A Reconsideration of Arabic and Persian Translations from Indian Languages.” Iranian Studies, vol. 36, no. 2 (2003), pp. 173–95.

Gangadevi. Madhuravijaya. Edited by S. Thiruvenkatachari, Annamalai University, 1957.

Guha, Sumit. “Empires, Languages, and Scripts in the Perso-Indian World.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 66, no. 2 (2024), pp. 443–69.

Haider, Najaf. “Translating Texts and Straddling Worlds: Intercultural Communication in Mughal India.” In The Varied Facets of History. Essays in Honour of Aniruddha Ray, edited by Ishrat Alam and Syed Ejaz Hussain, Primus, 2011, pp. 115–24.

Jayanaka. Prithvirajavijaya. Edited by Gaurishankar Hirachand Ojha and Chandradhar Sharma Guleri, Vedic Yantralaya, 1941.

Kovacs, Hajnalka. “The Preface to the Razmnamah,” In Translation and State: The Mahabharata at the Mughal Court, edited by Michael Willis, De Gruyter, 2022, pp. 67–122.

Moosvi, Shireen. Episodes in the Life of Akbar: Contemporary Records and Reminiscences. National Book Trust, 1994.

Mujtabai, Fathullah. Aspects of Hindu Muslim Cultural Relations. National Book Bureau, 1978.

Pollock, Sheldon. The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. University of California Press, 2006.

Pollock, Sheldon. “The Languages of Science in Early Modern India.” In Forms of Knowledge in Early Modern Asia: Explorations in the Intellectual History of India and Tibet, 1500–1800, edited by Sheldon Pollock, Duke University Press, 2011, pp. 19–48.

Pollock, Sheldon. “Ramayana and Political Imagination in India.” Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 52, no. 2 (1993), pp. 261–97.

[Razmnama] published as Mahabharata: The Oldest and Longest Sanskrit Epic. Translated by Mir Ghayasuddin Ali Qazvini Known as Naqib Khan (d. 1023 AH). 1979–81. Edited by Sayyid Muhammad Reza Jalali Naini and N. S. Shukla, Kitabkhanah-i Tahuri, 1979–81.

Truschke, Audrey. Culture of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court. Columbia University Press, 2016.

Truschke, Audrey. “The Mughal Book of War: A Persian Translation of the Sanskrit Mahabharata.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, vol. 31, no. 2 (2011), pp. 506–20.

Truschke, Audrey. “A Padshah Like Manu: Political Advice for Akbar in the Persian Mahabharata.” Philological Encounters, vol. 5, no. 2 (2020), pp. 112–33.

Truschke, Audrey. “The Persian Text of the Doha Ramayana.” In The Ramayana of Hamida Banu Begum, Queen Mother of Mughal India, co-authored by Marika Sardar, John Seyller, and Audrey Truschke, Silvana Editoriale, 2020, pp. 24–31.

Audrey Truschke is Professor of South Asian History at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey. She is the author of three books: Culture of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court (2016), Aurangzeb (2017), and The Language of History: Sanskrit Narratives of Indo-Muslim Rule (2021). She received a National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholars grant to write her next book, a single volume history of India from the Indus Valley Civilization until the present day.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, May 28, 2024