As Long As Language Exists: On Translating Katarina Frostenson’s The Space of Time

by Bradley Harmon

The poem and the translation are each transformative echoes of experience.

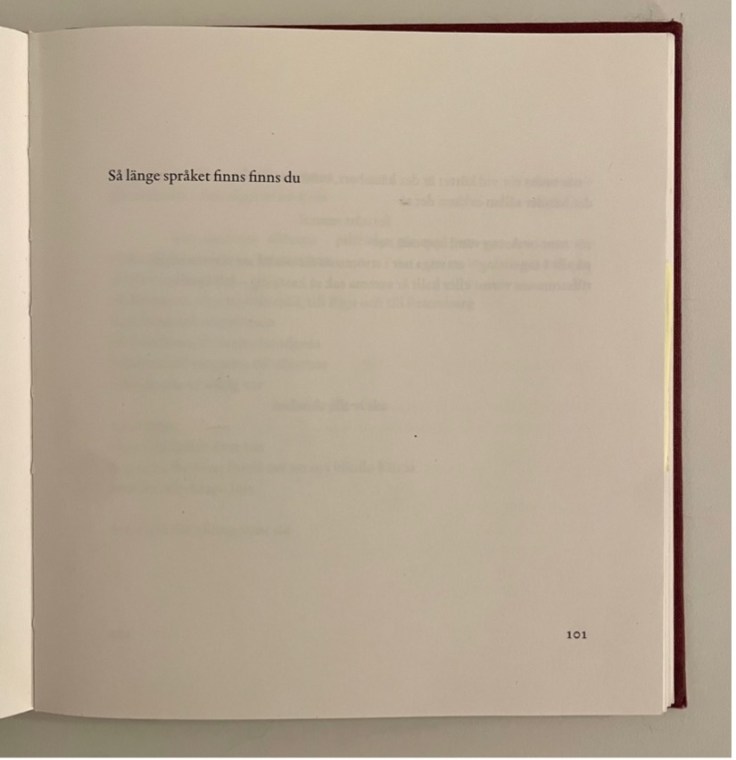

Så länge språket finns finns du

“As long as language exists, you exist”

This assertive phrase floats alone upon a paper sea of muted white, on page 101 of Katarina Frostenson’s plum-covered collection Flodtid (Floodhour; 2011), in the collection’s central, 18-page long poem “Orden mot” (Words towards). It was among the first pages I thumbed through when I stumbled upon a row of her colorful books in the Wilson Library at the University of Minnesota as an undergraduate. It’s one of those phrases that embeds itself within you as soon as your eyes pass over its letters. It’s also one of the few phrases I immediately understood during that first encounter—at least linguistically, having only started learning Swedish several years prior at that point. My interest was greater than my illiteracy.

I remember walking home from the library on that frigid February night in 2016, crossing the wind-blown, snow-soaked bridge that connected the campus’s west bank with its east as it stretched over the Mississippi. It was a two-mile walk from the library to my apartment, a half-hour at least.

As I trudged through the snow and slush, those words stirred in my head, inspiring not only thoughts and confusion, but an ineffable conviction. Resoluteness. As long as language was, I was. In that order. Language exists before me, beyond me. In the beginning was the word, we are told. And yet the only words that floated around my mind were those words. I couldn’t conjure any of my own, neither spoken out loud into the bleak midwinter air nor silent against the contours of my consciousness. Perhaps that one phrase had forced all others out of my mind, only to be whisked away by the wind, I’m not sure, but what is certain is that I repeated those words over and again on the way home, with different intonations and inflections, with varying pitch and prosody, with revolving rhythm, with and without rhyme or reason, in Swedish and in English. Så länge språket finns finns du. “As long as language exists, you exist.” Or, word-for-word: “So long language exists exist you.”

There are some small but, in my view, deceptively crucial differences between how the sentence works in Swedish and in English. For one thing, unlike English, Swedish grammar enforces strict syntactic inversion where there is a main “anchoring” verb around which other elements move—in this case, finns du (exist you). If the clause would stand on its own, it would be du finns (you exist). But because this main clause is preceded by a subordinate clause—så länge språket finns (as long as language exists)—that entire clause “kicks” the du to the other side of finns. Thus, så länge språket finns finns du. Though, if they themselves were writing the sentence, learners of Swedish would invariably slip up and write or say så länge språket finns du finns, which is syntactically incorrect in Swedish but maps onto the word-for-word order of a proper rendering of the sentence in English. “As long as language exists, you exist.”

Yet English feels less adamant than the Swedish to me for a few reasons. The first is that there is now no adjacent repetition of finns (exist), no side-by-side emphasis uniting language’s being with your being. If we abide by the rules of English syntax when transferring this Swedish phrase, language exists and you exist but never the twain shall meet. The second finns doesn’t vanish, but it does move, it comes later, ever so slightly delayed. It’s also worth noting that, despite its existential assertion, this phrase is uniquely intimate, with its apostrophic address. The poem is making a universal claim, yes, but it is speaking to you.

The second reason is that there is a comma. There doesn’t have to be, but without a comma the phrase feels to me almost flippant. To my mind, the comma helps slow down the rhythm and reinforce the assured register of the line. At the same time, it counterintuitively adds another degree of distance between the clauses, not unlike the separation of the dual finns. And while there is no period to close off the sentence, the first word is capitalized—the claim is resolute in its proclamation but leaves itself open to unresolved afterlives.

I could even give a third reason: in Swedish there’s no differentiation of verb forms between number or person, unlike English which still maintains a minimal distinction, with more or less variation depending on verb type. I exist, you exist, he/she exists, they exist, we exist. In Swedish, everyone and everything just finns, in the same shared conjugation. In terms of Swedish grammar, the existing of language takes the same form as the existing of you, of me, of everyone.

There are some cases where the translator may deem it necessary to bend or break the rules of English grammar to convey what the author is doing in the source language, but this is not one of those cases. Rending English in order to convey a linguistic specificity of Swedish that the poem is not trying to emphasize not only distracts from the point and the power of the phrase but also overdetermines it. Thus, in this instance the best option is for it to be “natural,” to recreate the Swedish text’s tone in English.

Frankly, this is hardly a typical translation problem. If anything, it’s more of a translator’s curiosity. It is not one of those infamous “untranslatables.” But the reason I mention it is because it gives a sense of the kind of nuance that Katarina Frostenson’s poetry explores and is famous for, in both theme and form. In Frostenson’s writing, there is no shortage of wonder before language, because “as long as language exists, / you exist.”

Philosophers have long told us in this or that way that we make and understand our world through our language/s. Some might express this as a matter of limitation, that if we don’t have the words for something it doesn’t exist. Think Wittgenstein and his most circulated phrase, “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Others see language as a matter of revelation, disclosure. Think Heidegger and his mystical predecessors.

If Frostenson has a philosophy of language, it is one that manifests through an attuned attention to how language and world are enfolded within each other and thus both exceed themselves, conjuring a yearning for something more primordial. “[A] language of flesh / all I wished for,” as it goes in the closing poem, which also speaks of a yearning to “become / that bareness / the gestures without adhesive, without / syntax // a speech without words yanked out, thrown to the world.”

While I doubt any poet would disagree with the sentiment that language, being, and humanity are entangled, Frostenson’s poetry puts this into motion by taking this abstract notion and exploring it through the matter of language, by which I don’t just mean the paper, ink and glue of the book, but also, and particularly, the substance of the embodied mind that reads and especially speaks the words that come to be represented on the page. For instance, whether explicitly or implicitly, Frostenson’s poems often draw attention to how the mouth employs air and muscle to produce contoured sound, be it how the word imorgon (tomorrow) decomposes in the poem “Tomorrows” or how the speaker of the poem “Existence” reminds the reader of how children learn to properly pronounce vowels (of which Swedish has nine) in turn encouraging the reader to reflect on, and perhaps also sound out, their own words.

The smallest building blocks of the Swedish language, the otherwise unnoticed minutia of words—especially sounds, especially vowels—are front and center in her poetry. In the history of Swedish poetry, Frostenson’s is unique for its primal preoccupation with sound, how sound can make meaning beyond or even without regard to semantics. That it is sound that speaks in and often drives her poetry can perhaps be understood in relation to the notion that language speaks, that we are bespoken by language as it emerges through and animates us. It is thus not surprising that the logic of her poems is often sonic.

At its most innovative, Frostenson’s poetry resists recourse to conventional ways of understanding, instead invoking a hermeneutics of the body, of association, of sound. Even if, as critics and scholars have argued, Frostenson’s poetry has grown more “accessible” and “open” in recent decades as opposed to her previously difficult and—according to the Swedish National Encyclopedia—“hermetic” writing, her tone remains consistent. Some critics describe her writing as serious, mysterious; others as playful, beautiful, graceful. If I myself were to offer a single adjective, it would be: meditative. The first definition that appears in my Google search is “relating to or absorbed in meditation or considered thought.” Suggested similar words include: contemplative, prayerful, reflective, musing, pensive, cogitative, rapt, philosophical, wistful. But it is the word “absorbed” that sticks out to me the most. To be able to meditate, to be able to absorb requires a radical openness to the world, to the flow of space and the flow of time. This is the common denominator of the poems in this book.

In this, I see an affinity between Frostenson and the American poet and critic Lyn Hejinian, whose seminal essay “The Rejection of Closure” expresses many profound resonances with Frostenson’s poetry. One shared quality is the preoccupation with the paradoxes that writing poses, which serves as the departure point for Hejinian’s text:

Writing’s initial situation, its point of origin, is often characterized and always complicated by opposing impulses in the writer and by a seeming dilemma that language creates and then cannot resolve. The writer experiences a conflict between a desire to satisfy a demand for boundedness, for containment and coherence, and a simultaneous desire for free, unhampered access to the world prompting a correspondingly open response to it.

In both theory and practice, the bind that lies at the core of writing is something that the writer must always contend with, through writing. Hejinian’s characterization of it in terms of opposing (therefore dynamic, therefore generative) tensions resonates with Carin Franzén’s description of Frostenson’s poetry as exhibiting a dual movement between collection and dispersion, and as aiming to resist the calcification of language in our contemporary age. While Franzén identifies and maps out a poetic deep structure of Frostenson’s poetics, Hejinian’s specific characterization of the writer’s dilemma has helped me to better understand Frostenson’s practice. That the tension between boundedness and openness is a key theme of The Space of Time is made more explicit by its original title: Sånger och formler, songs and formulae. For Frostenson as for Hejinian, the writer is both blessed and burdened, bound as they are to investigate language with language.

A brief excerpt from this book’s predecessor, Tre vägar (Three paths; 2013), gives a more concrete sense of Frostenson’s own poetics against the backdrop of these abstract notions. She writes that

poetry does not describe. With its lines it emulates [efterliknar] places and peoples and states, there are threads of clearly rendered reality running through, but it is primarily images that poetry writes forth; words bear words, images give birth to new images. They are awoken by sound, from them grows a world that is its own, emerging from the world.

Though the translator is not necessarily beholden to the beliefs of the author, this view of the work of poetry seems to me to lend itself sympathetically to the work of translation. Both are open processes which extend far beyond the supposed finality of the page. Both are phenomenological activities that depend on embodied relationality to (in the case of the author) the world, and (in the case of the translator) the text. The work of writing and translating is that of, to use Frostenson’s word, emulation. The poem and the translation are each transformative echoes of experience.

Frostenson herself is a translator, a theme that appears throughout this book alongside odes to philology and etymology. In Tre vägar, she reflects on the inspiration she received from American poet and artist Jen Bervin, specifically her book Nets, a transformative re-writing of Shakespeare’s sonnets, in which from the flesh of poetic corpus comes a skeletal extraction, a contemporary poet’s interpretation of the vital deep structure of Shakespeare’s verse. This leads Frostenson to further reflect not only on the inner workings of poems and poetry collections, but also on the movements of translation:

Now I’m also thinking of translation, and the powerful dream of being able to pull the song out of the song, out of what one hears, or experiences through the words of the other. Try with a hymn by Hölderlin, read it over and over again until the words sink in underneath and another poem rises up. It can also come quickly, like a flash of lightning from a clear sky, after a single reading: a new, inner poem emerges. An intercepted language, yes, a work of the genius poet that brushes past the text and overtakes the breathing she hears from it. Exhales another song.

The air we inhale is transformed when exhaled. The thing with breathing is that we need, but can never keep, the air we take in. And yet it leaves its mark on our body, and we on its, if it has one. Perhaps it’s the same with poetry, certainly so with translation.

Insofar as translator’s notes are to be a space where linguistic challenges are to be discussed, creative choices to be defended, and peace to be made, there are two instances particularly worth bringing up here, since both extend across the collection beyond individual poems.

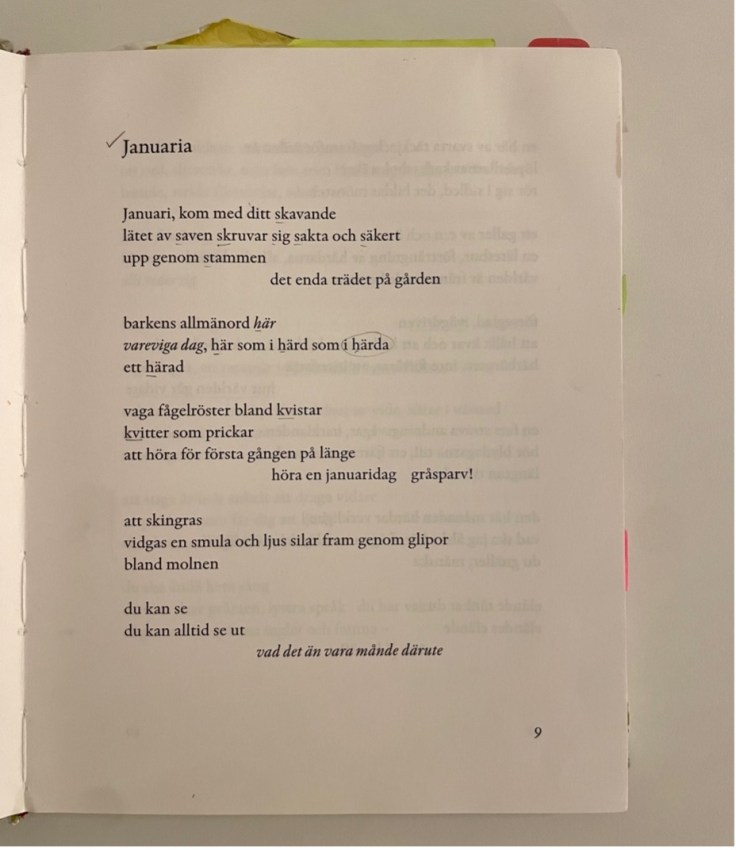

I mentioned above that Frostenson’s poems are often propelled by sonic associations. One such instance appears at the very beginning, in the opening poem “Januaria,” where each of the first two stanzas are oriented around a single alliteration: the first with the alliteration of initial /s/ and second with the repetition of the word här (here), each marked in the Swedish text below. Each conjures an almost propulsive rhythm (especially in combination with the arrangement of long and short vowels and syllable stress).

Januari, kom med ditt skavande

lätet av saven skruvar sig sakta och säkert

upp genom stammen

det enda trädet på gården

barkens allmänord här

vareviga dag, här som i härd som i härda

ett härad

In my English emulation, I found a way to roughly replicate each alliterating ensemble, though to differing levels of proximity to the Swedish. This was easier in the case of the first stanza, where I was able to get six of the seven Swedish /s/’s. Perhaps I could have gotten all of them by using the word “stem” instead of “trunk,” but in doing so felt too much of a semantic stretch in this case. I could have also wedged in another /s/ if I strained the reflexive verb skruva sig into “squirming itself,” but doing so would seem wonky and overdetermined. Luckily, läte became “sound,” without the definite article so as to further emphasize the rhythm. (In Swedish, läte generally refers not to sound as such—that would be ljud—but rather to how something sounds, usually in reference to animals.) The alliterative pattern shifts somewhat between Swedish and English but more or less maps on.

January, come with your scraping

sound of sap squirming slowly and safely

up through the trunk

the lone tree in the yard

It was more difficult with the second stanza, where the poem not only repeats sounds but also a word within a word. The wordplay is simultaneously sonic and semantic. In trying to emulate this in English, I had to move farther away from both semantic and sonic proximity in order to approximate both. Whereas Frostenson’s Swedish neatly draws attention to how the word ‘here’ (här) is built into other words (härd, härda, härad), my English relies instead on both homonym (here, hear) and quasi-heteronym (hearth, hear). It also effectively rewrites the phrase after the comma, rendering explicit and imperative (“hear the harmony”) what is implicit in Frostenson’s original (i.e. one sees and/or hears the här as part of the subsequent words).

the bark’s banal word here

every single day, here as in hearth as in hear

the harmony

The word här and the broader theme of place run throughout this collection, and in ways that don’t always transfer neatly. For instance, the poem titled “A Neighborhood” in English is called “I ett härad” in the Swedish. A härad is an administrative term roughly equivalent to a ‘hundred’ (in England) or ‘county’ (in the US), demarcated with stones. The härad and its sister term hundare (a direct cognate of ‘hundred’) no longer serve any administrative roles in Sweden. Given that the poem takes place in Stockholm city, where as far as I can tell there has never been a härad, I decided to instead use the more obvious word ‘neighborhood’ in its place. This is but one example of seemingly endless instances of philological, etymological, historical layers to be found in Frostenson’s poetry; and the choices that a translator needs to contend with.

The second instance is less about continuity amongst specific lines and more about maintaining continuity across poems. The collection’s second section, titled “In the Open” in English, is titled “I vidden” in the Swedish. According to the Swedish Academy’s Dictionary, a vidd is an “open landscape,” often used in the plural (vidder). It is also worth mentioning that here Frostenson is again playing with sound, in this case assonance. Throughout the poems in this section words such as vide, vida, vid, vidare, videskogar reoccur, all of which literally resonate with vidden (the open landscape). Though ‘in the open landscape’ in a geological sense might be the most literal, its figurative reach extends farther.

As I’m writing this now, my solution of rendering “I vidden” as “In the Open” feels like an almost obvious choice. Yet I recall having struggled over it for a long time. Early drafts of the translation had it as ‘In the Void’ and ‘Expanses.’ It didn’t start to click for me until Katarina pointed out that the Swedish translation of Austrian writer Arthur Schnitzler’s 1911 play Das weite Land (translated in English as The Vast Domain, Undiscovered Land, The Distant Land) was in Swedish titled De stora vidderna, literally ‘the great open landscapes.’ It seems that for some reason I had been thinking both too literally and too figuratively. Within a few hours of learning about the Swedish title of Schnitzler’s play, it occurred to me that “In the Open” was the right rendering. And I began to see resonances that emerged from associations in English and from the broader themes of the collection, and perhaps from also my fondness for Rilke.

The poetic-philosophical notion of “the Open” (das Offene) emerges from the Eighth of Rilke’s Duino Elegies, which begins so:

Mit allen Augen sieht die Kreatur

das Offene. Nur unsre Augen sind

wie umgekehrt und ganz um sie gestellt

als Fallen, rings um ihren freien Ausgang.

With every eye the creature gazes

into the Open. Only our eyes are

as if reversed, and entirely surround it

like traps around its free outgoing.

Like much of Rilke’s work, the Eighth Elegy has been the object of extensive, sometimes contradictory, commentary by critics, philosophers and literary scholars. What “the Open” is is far from agreed upon, and though I believe that perhaps its conceptual indeterminacy is the very point, there are some generally accepted aspects. Whatever “the Open” is or is not, the Elegy states that it is something borderless that only children and animals have access to. The adult human does not. It could be about nature, about modernity, about apathy, about spirituality, monism, transcendence, reason, knowledge . . . the list goes on. Though there are many spots throughout The Space of Time that might point to this affinity with Rilke, it is perhaps in “Siberian Song” where it’s most palpable. Adorned with the motif “Two children come wandering in the open [i vidden],” the poem tells of two young siblings who try to survive in the wild, open tundra of Siberian Russia. However one interprets the finer details of Rilke, if there were ever a context where one could come into contact with such a transcendent state to which “the Open” seems to refer, it would be the one conjured in this poem.

I am not the only one to pick up on this. The prominent Swedish critic Victor Malm contends that Frostenson’s writing “turns” at the millennium from a hermetic skepticism towards the Rilkean “Open.” Malm moves beyond taking “the Open” as a matter of poetic mysticism and suggests that for Frostenson it is a necessary attempt to write from perspectives beyond the human or the traditional poetic subject. For Frostenson, “the Open” manifests both in the poetic image and poetic form, and signals a more explicit ecological engagement reminiscent of what American scholar Lynn Keller terms “poetry of the Self-Conscious Anthropocene” which describes the “reflexive, critical, and often anxious awareness of the scale and severity of human effects on the planet.” This does not at all mean rejecting the human, but instead attempting to imagine, conceive and consider non-human perspectives in the world. This is most explicit in the poem “Trash Trail,” where the reader follows a human hand on its daily trash-tossing. In other words, the openness to the unknown, unfamiliar and unexamined is characteristic of both “the Open” and Frostenson’s poetry.

Aside from these loftier ruminations is the question how to render “I vidden” in a way that resonates across the imagined landscapes of the Siberian tundra in “Siberian Song,” the remembered cityscapes of “From Minsk,” the natural nightscape of “Voicegrass,” or the mindscapes of “Marina.” Thus the phrase “In the Open” makes sense to me, for a few reasons. One is that it gestures towards familiar figures of speech—if I find myself experiencing some interpersonal tension, I might say something along the lines of let’s just get it out in the open. It can also conjure notions of wilderness, wide open spaces, and the unknown of the world. It also brings us back to Hejinian and the radical openness of writing, and shows the extent to which even the smallest minutiae of Frostenson’s poetry can scale up to the overarching themes of an entire collection.

These examples are representative of the intricacies of Frostenson’s writing, and how a small detail can be connected to an entire ‘phase’ of her career. As a general principle, because I can’t replicate every trick or clever phrase that she makes in Swedish, I tried to tease out ambiguities and wordplay whenever I could in English. And without sacrificing sense, I tried to emphasize sound whenever possible.

It’s a tired rhetorical trope that things are lost and found in translation—indeed I can admit that my discussion of specific passages might constitute a lost-and-found inventory of language. But it can also be a matter of compensation, of adaptation, of calling and responding across languages, of emulation.

Having worked with these poems off and on for the better part of eight years, I do not pretend that any single one of my translations is ‘done,’ despite their presence on the page. They are still open, open-ended, in the open.

When, in the opening poem “Januaria,” Frostenson writes of a language that moves forward in time, one that continues to resound, resonate, reverberate into the future, whose words are transformed, that is the work of the poet and the work of the translator.

This essay is a version of the author’s translator’s note to Katarina Frostenson’s The Space of Time, published on 15 November 2024 by Threadsuns Press.

Bradley Harmon is a writer, translator and scholar of Nordic and German literature, philosophy, and cultural history. His translations from Swedish include Katarina Frostenson’s poetry collection The Space of Time (Threadsuns, 2024) and Monika Fagerholm’s novel Who Killed Bambi? (Wisconsin, 2025). A PhD candidate at Johns Hopkins University, he has been an ALTA Emerging Translator Mentee, an American-Scandinavian Foundation fellow to Sweden, and a Fulbright scholar to Germany. He currently lives in Berlin.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, November 26, 2024