Following Threads and Leaving Traces: The Archive and Literary Translation (Part 2)

A Conversation between Breon Mitchell and Chris Clarke

We must realize that the creative life is one life. It’s not the life of a poet on one hand and the life of a translator on the other.

The following is the second installment of Chris Clarke’s conversation with Breon Mitchell, literary translator and former director of the Lilly Library at Indiana University-Bloomington, which took place over the phone on November 6, 2023. Part One appeared here at Hopscotch Translation on October 22, 2024, and can be found HERE.

The conversation has been edited for clarity.

CC: Breon, in a previous interview, you spoke about the difference between the translators’ archive and the poet-translators’ archive. I worked on a research project some years ago that started out as a project for Ammiel Alcalay at CUNY for his great Lost and Found research publication series. One of the researchers involved in that group had come across a partial Muriel Rukeyser translation of Arthur Rimbaud dating from the 1940s, this was in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library. The people that were involved didn’t work with French or translation, so Ammiel reached out and asked me go in to evaluate it. Following the archival thread, I ended up getting lucky and finding the rest of that same draft and part of a different draft that completed her translation of A Season in Hell; these were in with her papers in the Library of Congress. So between the two archive sites, I was able to put together a full manuscript, which was pretty cool.

While I was at the Library of Congress, I went digging through the rest of her papers that they hold. And of course, everything that has been preserved there has been kept not because she was a translator but because she was a famous poet. These are the only translation archives that we tended to have prior to the advent of the few that exist like the one you’ve built in Bloomington.

BM: You know, for that very reason, it is absolutely the case that the Lilly Library, while I was director, was able to get some wonderful translation archives of poets where the initial institution they turned to, which was generally one where they’d been an undergraduate or had done a graduate degree, had said, Yes, we’d like to have your poetry manuscripts or your novel manuscripts, but we don’t have room for your translations. To me, it’s just unbelievable that a rare book library or an archive could ever think that. It just shows how far we still have to go. We must realize that the creative life is one life. It’s not the life of a poet on one hand and the life of a translator on the other. I could name four or five different people who said, my library took my manuscripts, but they didn’t want my translations, so we took them, and frankly, because they were translating some very well known people, the translations are probably looked at more often than people come to look at their poetry.

CC: That’s what was remarkable about the project in the Rukeyser archive, and why I ended up going back and doing a second project. After the initial publication of the Rimbaud translation at CUNY, I have an article coming out next spring in The Romanic Review. Still, I ended up finding so much interesting stuff that I had to cut substantially from that article; there was likely enough raw materials for three four more articles. Her translation of Erika Mann was there, for instance, she translated School for Barbarians [1938], and there was correspondence between her and the Mann siblings. Also her translations from Spanish through the forties and fifties, and her early French translations; she translated some Louis Aragon poetry quite early on. And then of great interest to me, she spent a number of years translating Gunnar Ekelöf from the Swedish. This she did with help from a scholar from Columbia, Leif Sjöberg, who was the go-between and provided her ponies, but also communicated with the poet. There’s two parts of a three-way chain of letters, where you can’t see what Ekelöf is saying directly, but it’s being reported back to Muriel in English by Sjöberg. These make for a fascinating look at this intermediary process.

The project I chose to focus on first, because there were far more materials and it grabbed my attention first, involved thirty years of correspondence between Rukeyser and the poet she invested the greater part of her career translating, Octavio Paz. Their correspondence starts off at a time in the forties when she has recently discovered him, and the letters continue for nearly thirty years, to a time when she’s quite late in her career and he has become an international figure. It’s a very interesting saga, and it offers an interesting look at their differing points of view on poetry and translation. What is most remarkable to me, as fans of both of their work, is that these materials are just sitting there waiting to be read.

BM: You know, there’s so much like that to be discovered. One of the ones that I was mentioning as an example, William Jay Smith, was someone who was an undergraduate at Washington University in St. Louis, but whose translation papers wound up at the Lilly Library. William Jay Smith, as you may know, did all sorts of State Department tours in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, and in every case, he got trots in English provided by authors who later became quite well known, and he translated them into English, and they were published. So among his books are presentation copies from Voznesensky and other important Russian poets. And it’s a situation exactly similar to what you’re describing. Certainly, if they wanted to look around a bit, anybody could write a book about those poets who were translated from languages the translators didn’t know with the help of trots. And especially if the trots still exist, which actually often came from the author, who didn’t know English well, but well enough to say, “This is what my poem says.” These poet-translators then transformed it into a poem which is now often read and published as their poetry. Extremely interesting.

CC: Rukeyser did a fair amount of that, where she would work with ethnologists or linguists, often people from Columbia University, who would come back from Tahiti with field recordings of Marquesan, Paul Radin would provide her with transcriptions of poetry from Inuit artists, and her versions would end up in journals or even in her own poetry volumes.

BM: Yes! I was looking at some of the earliest translations of Beckett, translations which nobody even knows exist but that I’ve discovered, early translations into Albanian. The translation of Waiting for Godot, the first one into Albanian, was done by a leading poet of Albania in 1969. I was looking at what else he had done, and found out he worked with Ismail Kadare; the two of them published a volume in Albanian of Vietnamese poetry. And I’m sure they didn’t know Vietnamese. So there’s an interesting situation where I think they must have been working from the French. There could be a really interesting study of the Vietnamese, French, and Albanian, since it involved, on the one hand, Kadare, who, if he ever is forgiven a little for the past, will win the Nobel Prize eventually. And this poet, I didn’t know him, but when did a little research, I found that he was the most important Albanian poet of the twentieth century. Anyway, this is the sort of translation study that is made possible by an archive, because if you don’t have that archival material, there’s not much you can do.

CC: Well, that’s just the thing. With the Rukeyser papers at the LoC, there is a finding aid, but it’s certainly not clear from that list of box titles what in that collection will prove to be interesting, or what is related to translation. It was the same experience when I visited the two Raymond Queneau archives in Belgium and France. That leads me to perhaps a more future-looking question: Now that the idea of the focused translators’ archive has taken off, at the Lilly in Bloomington and elsewhere, is there maybe a need down the road to come up with some sort of a searchable, centralized database that would allow these archives to communicate all of what they contain to one another?

For example, during my first real archive trip in 2013, I went to the Raymond Queneau archive that André Blavier assembled in eastern Belgium, where they had a typed list that had been provided by a scholar called Kestermeier, who had cross-catalogued the holdings of that archive with another one that had previously been in Limoges, and had then been moved to Dijon, as well as those at the the library in Queneau’s hometown Le Havre, and others at the Ransom Center in Austin, Texas. While it was great that there was this somewhat dated typed list, there wasn’t always a way of knowing which archive held which item. They did try to share duplicates of things, but back then, of course, it was by mail and by photocopy. So many of the folders contained stamped photocopies from other archives of the piece that they didn’t have, but not always even that.

This also brings to mind a lecture I heard about the difficulty of doing research on Baudelaire early in the last century, which was that when his estate was dispersed, they sold his letters off individually, and they ended up in hundreds of different collections around Europe. In such a case, if you ever want to read a full correspondence, what do you do? At the end of the day, it can’t all go to the Lilly Library. Unfortunately, the Lilly won’t ever have the budget or the space or the staff to do that. But with the digital tools now at our disposal, perhaps some sort of a system can be set up for these archives to communicate and permit broader and more defined searches. What are your thoughts on that?

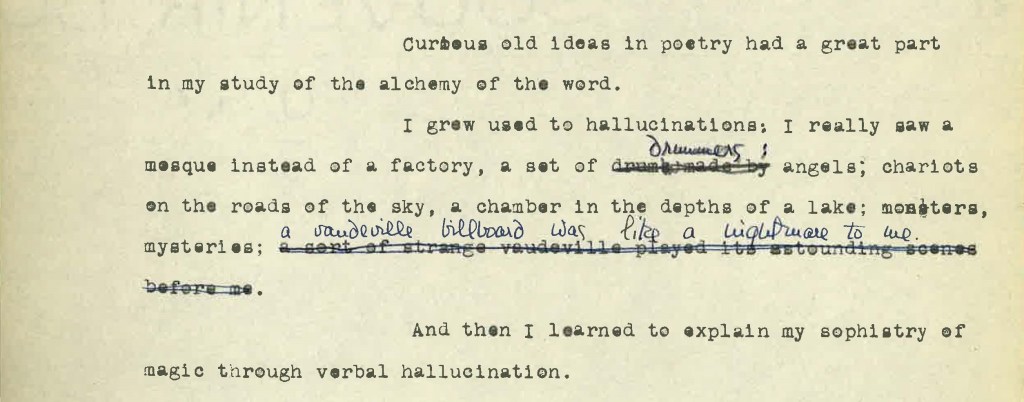

BM: It is something I’ve thought a good deal about, and it’s a problem that isn’t totally intractable, but it requires many people who are willing to spend much time, and work very hard at it, and there are few people who seem to have the time to do that. I’ll give an example of the sort of problem that arises. The first step in the problem when it comes to establishing a sort of database that lets you know who has what where is for the individual institutions that hold the material to know what they have and to describe it. Every institution I know is a long, long way from being able to do that. We have at the Lilly, for instance, both William Weaver’s papers on Umberto Eco, and Barbara Wright’s papers as well. I went through these in some detail and tried to get information on what we have out to people in the field. Recently, we’ve had a very fine scholar from Poland, who’s working at the Lilly Library on translation issues and the history of translation, and she said, You know, if the Lilly could just take its inventory of the work and have a more detailed and clear inventory of what the material is, it would be a huge help. For instance, she said, you say you have a corrected typescript, but you don’t make it clear whether the corrections are the authors or an editor’s or a combination of the two. Well, in many cases, we have gone into that. I’ve done it for my own things. And the fact of the matter is, it’s not easy to distinguish the various hands that are making corrections to a manuscript. If you know Beckett’s hand well enough, as I do, I can tell you whether that’s Beckett’s hand or not. But I won’t know whose those editorial hands are and which percentage is which without going through every page of a manuscript.

In other words, the notion of step one, providing a really clear inventory of what the institution has, is an extremely time consuming, difficult thing that requires not just catalogers who know what they’re doing in terms of describing things, but also catalogers who are academically scholarly sleuths who can distinguish and who would know, when Arthur Miller is writing to Joe, who Joe is. Or know whose hand that is, when it’s an editor, if it says Drenka, they either know it’s Drenka Willen or they don’t, but it’s very likely that nobody in the library is going to know. It’s going to take the translator or the author who knows for us to know.

This is why, just to jump back for a moment to what translators should do for their archives, and authors should do this too, they have to help as much as they can before their material gets to the library, by saying who these people are and who it is that’s writing on the manuscript. I’m doing it myself in my manuscripts because I have that interest in it. I’ll add a ‘this is so and so here,’ with corrections by whoever corrected it, I put a date on the manuscripts when they were done. All of these things can’t be done by the library. So, step one, getting the institution to do it is very, very difficult. It takes a long, long time. I don’t want to say it can’t be done, but it’s hard.

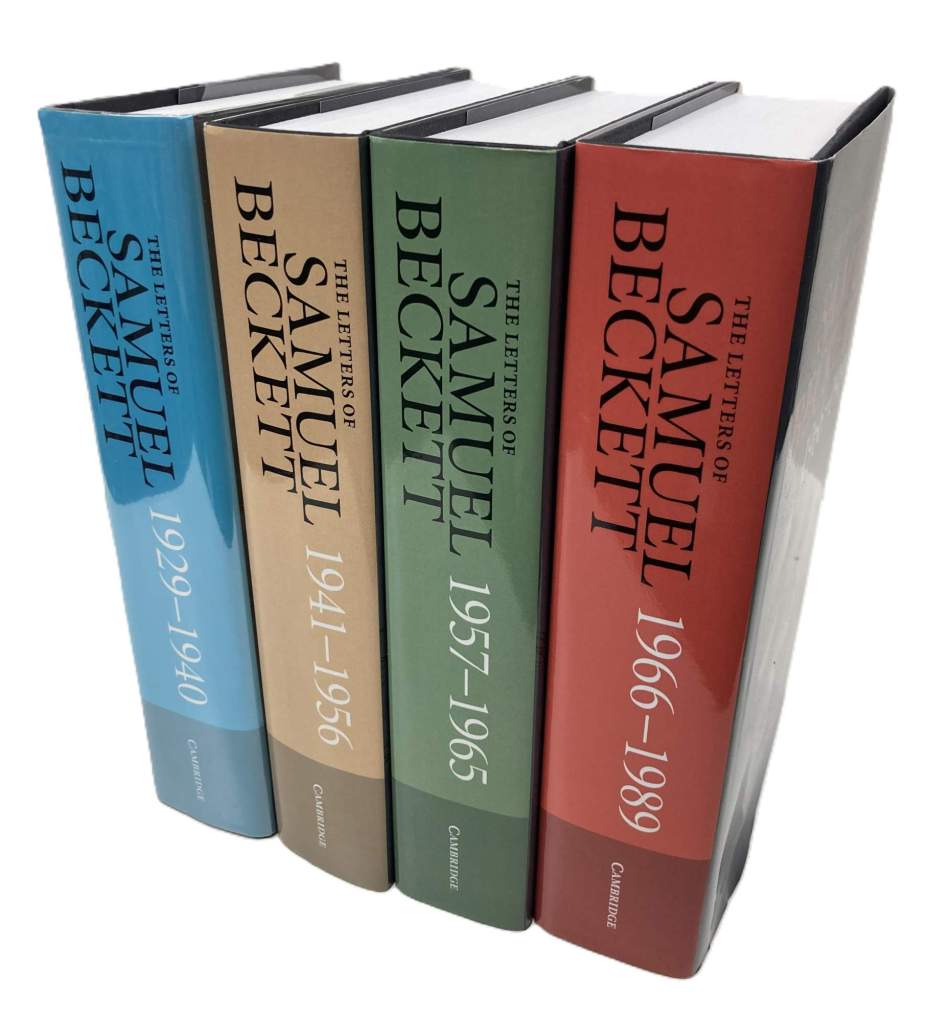

Number two, someone has to do something like what Lois Overbeck has done at Emory with Samuel Beckett’s letters. Take just Samuel Beckett’s letters. At Emory, Lois Overbeck has done a correspondence locator where you can discover where every Beckett letter held at an institution in America is, and there’s a line or two about what the letter says. This is tremendously helpful. But Lois has had graduate students and scholars working on this for years. The four volumes that came out of Beckett’s letters are just a small part, of course, of the letters that he actually wrote.

So, what would it take to do something like that for translations, to let you know the various institutions that have material on the translators or authors you’re interested in? It would take somebody or a group of people to actually agree, we’re going to do this. We’re going to look, we’re going to contact the institution, we’re going to ask them to take part in a project to get the news out to people in some way, and that’s if the institutions have detailed inventories of what they have. And even so, to get that digitized, to put it online so that people could say, Okay, you’re interested in Rukeyser, for instance, here are the eighteen places you should go, and here’s what they’ve got. They would love to provide digital images, but they can’t always do that; they don’t have time or the money.

CC: I see what you mean. Having spent a decade conducting research on Raymond Queneau, I feel that by this point I could probably eventually figure out who most of the people are that he mentions in his letters, and I’ve spotted the different hands on some manuscripts, but I’ve spent the better part of a decade getting to that point, and a graduate student working in the Lilly doesn’t have that background. Specialists can’t be everywhere at once.

BM: Exactly. That’s just the way it is.

CC: For a couple of years when I was in graduate school, I was involved with an archive project where a French research group that had a large Euro research grant was had begun the project of digitizing the Oulipo’s archive. They were working on the first with twenty-five years, 1960 to 1985, if I remember correctly. Twenty-five years worth of the group’s monthly meeting notes and all of the random documents that were attached to them. Working on that project, I quickly saw how complicated and time consuming it can be to get the materials up online, but then we also had to tag all of the names and terms that needed to be cross-referenced and searchable. There was a team of volunteers working on this and a team of coordinators keeping things moving, and all of this grant money involved… plus the thousands and thousands of dollars it costs to have it all scanned at high resolution, and so on. And that’s just a single archive for one group with a handful of writers.

So I can definitely see the issues. What would be a good start, however, would be if the institutions holding an archive of translators’ works could at least compile a list of the people whose work they are holding, and for that to then be shared to a larger list. If that were the case, I could use something like WorldCat.org, and delimit it to translation manuscripts or translation-related correspondence, and search authors directly in that engine, and that way it would be possible to know that I would need to go to the Ransom Center to look at so and so’s papers. And then maybe while I’m at the Ransom Center, I could contribute to the process by leaving some more detailed notes about what it is that I’ve examined there, according to my own scholarly insights.

BM: I remember at least fifteen or twenty years ago, there was at that time a published source that was available where, if you were interested in X, you could look X up and it would list five or six institutions that had material on that topic. That was a published book, and while now it’s out of date, that’s the sort of thing you’re thinking of. Something you would have online, and it would be easy to use…

CC: And it could be updated regularly.

BM: Right. Say you’re interested in Samuel Beckett. Because I am interested in him, I could say, well, you’ll need to go to Emory, you’ll need to go to Austin, Texas, to Wash U. in St Louis, Ohio State, McMaster, Boston Public Library, Reading University, you need to go to IMEC in Paris. You know, I could list twelve different places and, if you were really interested, you’d have to go to those places, but you could not find out what’s in those places easily without actually going there. At IMEC, in particular, they have made a real effort to digitize material, to say what they have, and to get other institutions to copy material from French authors that they could share, so that they could exchange that sort of information. They have worked on that.

But for a different example, at the Lilly we have the Red Dust archive. Red Dust was a publishing house founded by Joanna Gunderson in New York. She has since passed away. This collection has a huge, long correspondence with Robert Pinget, about all the publications of his work here in America, and this is all at the Lilly. If you’re interested in Pinget, you need to come to the Lilly. Well, you might say, Why doesn’t the Lilly just digitize it all and send it out? Well, the answer is, the Lilly is digitizing as fast as it can, as much of the two million manuscripts we have… Some manuscripts are one letter, some are 800-page novels… And everybody wants something.

CC: It’s all extremely time consuming, too. I often find myself scanning book excerpts for my students, and when I’ve finished, I think, Hey! I just spent an hour scanning, and I’ve only made three sloppy PDFs.

BM: It’s all quite overwhelming. We have to keep thinking about this. Now, I would have good news for somebody who was interested in Georges Perec, which you would be, and that is that David Bellos has kindly donated his papers to the Lilly, those from after he left England and came to the United States. So, while we don’t have the early novels that made Perec famous, we do have later works and a lot of Perec things from Bellos, plus everything from when he wrote his book on Perec. And for that, he copied the information and manuscripts and letters from all over the world, and kept them all. So if you come here and have access to his papers, you don’t have to go to Sweden in order to read the letters that are held in Sweden, for example, because he made copies of everything, and it’s all arranged. So the answer, at least for Perec, is simply to go to the Lilly Library and look at the boxes that are already assembled and put in order by month. When the donor has done this work for us, it’s a great help.

CC: Another point I’d like to raise is simply one of practical use for translating, and of how much of a help it can be to have access to a translator’s archives, If you’re working on the same author.

BM: Yes.

CC: For example, I’m translating Queneau again right now, and he died the year I was born. I can’t ask him questions, and he wasn’t always very forthcoming about his own writing, not in a concrete way. But Barbara Wright corresponded with Queneau when she was translating him. He didn’t always tell her that much, he was a playful fellow. She famously misunderstood one of the Exercises and translated it quite creatively. He noticed that, as his English was definitely good enough, but he chose not to say anything, because it was in the Exercises in Style, and he thought what she did with it was another interesting possibility.

I’m currently working on translating another of his books with two colleagues, and it’s a very difficult project. It’s really quite tricky. It’s so packed full of allusions and puns and obscure vocabulary, and scientific and mythological references, which is the main reason I invited two brilliant translators to come work on it with me. The greatest resource I’ve found, externally, is again at its roots an archive discovery. Chris Andrews, the great Australian translator, wrote his dissertation on precisely this book, and it turns out that a lot of the insider information he made use of came from Queneau himself, who had explained a good number of these puns, some of the most obscure ones, to his German translator, Ludwig Harig. The correspondence between Queneau and Harig has some of the answers we’ve been looking for, and we just need to read it and see where it leads.

BM: And where is it?

CC: To be honest, I’m not quite certain where it is at this point, because I can’t get overseas to look right now, but it’s out there, either in Dijon or in the collection at Verviers, housed in the library André Blavier worked at in eastern Belgium. It would sure be great if there was a database that could tell me where it was, but in this case I’ve already got a good idea.

BM: That’s very interesting! I actually translated Ludwig Harig. So in the Ludwig Harig materials, there ought to be at least something from me. He was a great writer in his own right, as many German translators were. An interesting thing I should mention, just in passing, is that I can’t think of any major author who never translated anything. I mean, they all did. Joyce, Beckett…

CC: …Borges, Calvino, Nabokov, Baudelaire, Schwob…

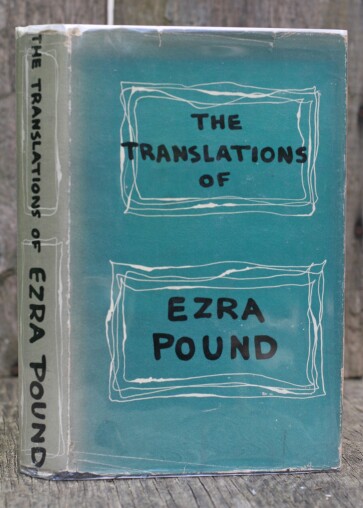

BM: And on it goes. We also have a lot of Ezra Pound’s translations in the Lilly, if you’re interested in his translations. In a way, then, scholars are not necessarily going to be thinking just of translators’ archives, because everybody is a translator. In the Virginia Woolf collection out at UCLA, I think part of her translations are included, and they’re there because they collected Virginia Woolf materials.

CC: At the end of the day, that’s what my dissertation ended up exploring. It wasn’t just an analysis of Queneau’s work as a translator, but more a meditation on what those years he spent reading in other languages, translating literature, and working in publishing foreign literature in translation, how this all affected his writing. It’s all tied together.

BM: Exactly, that’s so interesting. I remember Paul Auster spoke to ALTA one year down in Florida, saying, Translation is the perfect preparation for a writer, for becoming a novelist. And so many have thought in those terms, too.

CC: For scholars who work on the 20th century, which I do, especially the early and mid-century years, it’s just crucial to be aware of these practices and networks. This perpetual exchange between translation and creative writing. I interviewed the elder statesmen of the Oulipo, those who were still with us, when I was writing that dissertation. I recall the great Jacques Roubaud telling me that when he started out, it was just a given fact: if you want to be a poet, it was 50% translation, 50% poetry. The more successful he became as a poet, maybe he translated a little bit less, but it was never because he wanted to do less. It was just the way it worked out.

BM: There are a couple of last things I should say about translators and their archives. This is one of the different ways to look at the translators’ archive and how it can be used. There are always going to be people who wonder, I have an archive, and it’s an interesting one. How do I go about it? What do I do? One of the things that you do, as we talked about before, is that when you’re young and as you’re going along, you make your archive an interesting archive. You do this by the sorts of things you say and the sorts of things you generate. That’s one thing. Another thing is to at least have some sort of succinct listing of what you’ve got, and to keep that list of what’s in your archive as up to date as you can. Often, an institution is contacted by a translator who tells them, Look, I’ve been translating these three wonderful writers, I’ve archived all my materials, and I don’t want them to be lost, but I don’t know what I’m supposed to do with it all. Most of these institutions—if they’re interested in literary translation at all, as they would have to be—will say, Well, what have you got? What’s in your archive? How many boxes would it be? Are we talking 150 boxes, or do you have two or three boxes? So it’s important not only to have an archive, but to have your own listing of what’s in the archive, and to try to keep it up to date.

Another thing that the translator often says is, I’ve got everything on computer, and I’ve got everything in emails. Well, the institution is not going to be able to read through your emails.

CC: Hah! No, nor should they!

BM: What I always say to people is, Yes, a lot of the most interesting things that you have to say and do with your translation are going to be in emails. But for every two of those sorts of emails, you also have the eight emails where you say, Let’s meet for coffee, and let’s do this, and here’s that, and I mean on Monday, but I say tomorrow, that sort of ambiguous and uninteresting communication. In this case. the translator has to go through his or her own emails and print out the ones that are substantive and interesting, and keep them. And if you don’t do it shortly after the exchange takes place, it’s likely not going to happen. Recently, I’ve been going through a lot of email correspondence with people who are interesting people, and I can pick out and print things that I know people would be interested in reading, exchanges that scholars would be interested in reading. But I have emails from more than ten or fifteen years ago where I didn’t get that done. I wasn’t thinking of it, and those might as well be lost because my email, I can go back ten or fifteen years, but I can’t go back thirty years.

CC: That’s a great point. I think that’s where I’ll start. I would like to make a list of all of the writers that I’ve translated, or even just writers who I’ve corresponded with, and go back through the five or six different email accounts I’ve had over the last twenty years, searching for them by name and by address, and then read through them one at a time and print them to PDF if they are interesting. I think that’s the way to do it.

BM: Yes. And if you print them out on paper, that is the best way, it will last two or three hundred years that way. And just keep a file as you go along, if you possibly can.

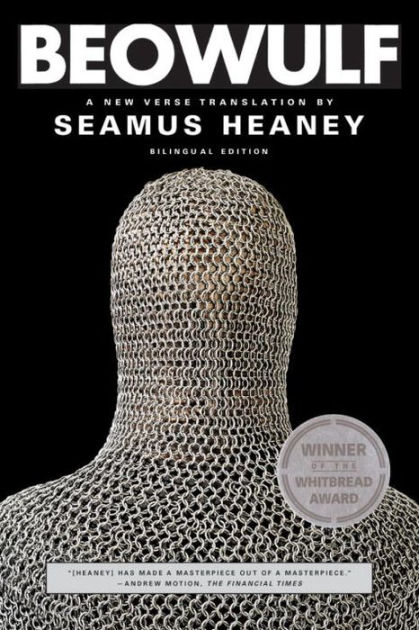

When Seamus Heaney was working on his translation of Beowulf, he was in contact with Alfred David, who was a specialist in that area at Indiana University. Such a specialist that Heaney came to him to read the translation and vet it and offer corrections and so forth. David was a colleague of mine, and he came to the Lilly, and asked if I would be interested in having this. And I said, Yes, that’s really, really interesting and important. Heaney, in his introduction, thanks Alfred David for having read the entire manuscript, and says something to the effect that any mistakes that are still there are entirely my fault. Anyway, the bottom line of this is that everything that David gave us was faxes; he and Heaney had been faxing back and forth. And those faxes were all fading. As soon as we got them, they had to be immediately copied onto paper if they were to last. If we hadn’t done that, they would be blank sheets of paper by now. And so there’s that to think of, too, taking care of what you’ve got. If you have books that are moldy, they’re never going to make into an institution. They can’t be brought into a rare book library. If your manuscripts get wet and have mold, they won’t be preserved, they’ve got to be clean and dry. So you have to think about these things; don’t just put them in a wet carton in your garage and hope that an institution will say, send them all.

I have a few more things to say about putting your archive together. So, you have assembled your papers, and you’re thinking, Okay, what do I do next? We’ve mentioned a couple things already: you create an archive that’s interesting, and you list its contents or know what’s in it, so that you’re able to tell an institution. The next thing you really want to think about is which institution would be the proper place for it, and start there. For instance, if you’re a New York translator and poet who spent all your time interacting with people in New York, you might consider the New York Public Libraries collection, or Columbia University’s library, or someplace in the area. And if that doesn’t work out, then you might think of some other place.

Another way to think about it would be, Is my archive, wherever it’s going to go, will the materials of anybody else of interest be there as well? A lot of scholarship is comparative, looking at what different people do. The Polish scholar who is with us right now is at the Lilly not because of a particular person we have here, but because we have fifty or sixty different translators whose materials all show similar problems and thoughts, and she can go through all of this material. She’s interested in the history of translation, not just a particular translator. And so it would be nice to be in the company of translators you find interesting.

CC: Yeah, that makes great sense.

BM: And there’s one thing that is also a most delicate thing, and that is the financial side of it. People don’t like to talk about it very much. I’ve mentioned this, I think, in the other interview I did, but it bears repeating: translators’ papers don’t have much market value, that’s just the way it is. But if they contain letters from Nobel Prize winning authors, those letters have value. This is market value, not scholarly value. The translators’ papers are tremendously valuable for scholarly research and the history of creative endeavor.

But say you go to a New York bookseller and you say, I’ve got my translation of Baudelaire here, they’re going to say, Yes, and what do you think we can do with it? You can’t sell that. The two ways it tended to work with the Lilly over the years, well, I was often working with friends at first. Most of them donated their papers the same way that I donated mine. But donating your papers is not the end. If you donate material that has value, not because you yourself created it, but because someone else wrote you letters or inscribed books, they have a value, and you can have that appraised, and you can get a tax deduction for that. In other words, you can get financial reward for donating material, if you have worked with the sorts of authors that booksellers in New York are interested in.

There can also be the situation where material is worth something because of the translator himself, that’s possible too. We have purchased archives. In the past, I have received materials from various manuscript dealers. For example, they might say, We have a collection of Edie Grossman’s papers, and we want to sell them. That’s quite reasonable, and they will say, This is what we have, and this is how much we want for it, and then the library or institution can decide whether or not to buy it.

All of this to say that for those people who donate archives, the library or the institution can help them understand what tax advantages there are to donations, and there are tax advantages to it. You cannot, however, get a tax advantage for your own letters or your own manuscripts, that’s only for someone else’s.

CC: You’re suggesting, then, that I should start trying to do more paper correspondence with authors and less email.

BM: That’s right, because emails are of zero value on the market. They’re very important otherwise.

So, if you donate, if an institution takes the donation, for those people who have an archive and they think, This archive should be worth something, I’d like something for my life’s work in terms of actual money, and not just a donation with a tax credit, well, the institutions cannot just offer money. Whether a state institutions or private institution, even if they want to, they don’t. What you have to do in that case is you have to have the materials appraised by a certified appraiser who says, I’ve looked at Chris’s archive and it’s worth $15,000, and then the institution looks at that and says, Okay, that’s what we can pay. Or they say, We can’t afford it. They can say whatever they want at that point, but they can’t just buy an archive that hasn’t first been appraised and offered to them at a particular price. The problem with appraisal is that the people who do these appraisals are high quality specialists in manuscripts, they’ve done the papers of very famous authors and certify their work, and they charge a lot. Some of them will charge as much as $1,000 a day to do an appraisal, and it may take a while for them to figure out what you’ve got and what it’s worth.

That’s another side of if, then. You have to ask, For the appraisal figure I’m going to pay, is my material worth putting that money out? It’s investing in it, in a way. Whenever I talked to anyone myself, when I was director, I tried as gently as I could to discuss with them and figure out what their situation was, and what they wanted to do. We do get people who will come into the Lilly Library with a single rare book, where it isn’t clear whether they are saying, “Here’s a book, would you like to have this for free?” or whether they are saying, “Here’s a book, would you like to buy this? And how much would you pay me for it?” One of the delicate things with any archive is whether the person is interested primarily in the preservation of their work and making it available to others, or are they primarily thinking, this is something that I need to get paid for. That was always on a case by case basis.

In Edie Grossman’s case, she and I never talked about money, but there was a dealer who did, and that was all handled by somebody else. I would say that 90% of our translators’ archives, at least, are donation with a tax advantage. That’s something to be aware of.

CC: Excellent. Breon, I really appreciate you talking about this with me, it’s all very fascinating, and yours is truly a unique perspective on this. Thank you.

BM: And for your own archive, remember the Lilly Library. I would be happy to talk with you about any details you want to discuss about your own library. Your archive would be a good one for us to have.

CC: Great, I will, and I’ll include a transcription of this very conversation in my pitch to the Lilly when the time comes.

Breon Mitchell is a founding member of the American Literary Translators Association and served as President in its early years. His major translations include Franz Kafka (The Trial), Günter Grass (The Tin Drum), Heinrich Böll (The Silent Angel), Siegfried Lenz (Selected Stories), Uwe Timm (Morenga), and Sten Nadolny (The God of Impertinence). As Director of the Lilly Library at Indiana University he devoted himself to preserving the literary archives of major English-language translators both here and abroad.

Chris Clarke is a literary translator and scholar. He currently teaches in the Translation Studies Program at the University of Connecticut. His translations include books by Raymond Queneau, Éric Chevillard, and Julio Cortázar, among others. He was awarded the French-American Foundation Translation Prize for fiction in 2019 for his translation of Marcel Schwob’s Imaginary Lives, a prize for which he was also a finalist in 2017 for his translation of Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano’s In the Café of Lost Youth. His translation of Raymond Queneau’s The Skin of Dreams is newly out from NYRB Classics.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, December 10, 2024