On Translation, Codification, and Something in Between: Language in the Paintings of Martin Wong

by Addison Bale

Does painting language—placing language in a pictorial context—fundamentally alter its sign value/function? And by converting text into image, does painting become an act of translation?

After looking at Martin Wong’s painting Attorney Street: Handball Court with Autobiographical Poem by Piñero a lot, it’s become clear to me that despite the interplay of three representations of language, there’s a strong urge to conflate their proximity and overlapping sentiments with something like translation, but that in fact, translation is not actually happening. Then I get lured back into the paint, I second guess the image or how I read it. Right, I’m reading it: the undulating words of a poem knifed into a dappled gray sky, Little Ivan’s graffiti smacked across the wall of the handball court, and that idiosyncratic block of hand signs spelling out words in the ASL manual alphabet. Not to mention the historic context, which like a film still lends us that synthesis of style and grime that was so characteristic of the Lower East Side in the 80’s. Screaming graffiti; chain-link fences impressionistically rendered as faintly dotted gleams that denote the metal; trompe l’œil of the bricks and wood grain casting our street scene as prop architecture, like a caricature of itself. Everything is legible, plainspoken, and the poem adds emphasis to the LES-ness—you can practically hear the voice of Miguel Piñero shelling out the attitude of a whole neighborhood: “RAISED BETWEEN TWO 45’s – ON A SATURDAY NIGHT – WHEN THE JUNGLE WAS BRIGHT AND THE HUSTLER[S] WERE STALKING THEIR PREY -.” The script is dark and receded but looms like a skulking counterpoint to the graffiti which is bright enough to look fresh, and therefore, as all graffiti, fleeting.

I fall again into a question which leads me to the issue of translation: Where does the painting end and writing begin? Or vice versa? And if painting and writing are not the same (which is the general consensus in the context of Western art) then how does writing—how does language—change once it’s rendered in paint?

Oil on canvas, 35 ½ x 48 in. 1982-84.

Copyright Martin Wong Foundation

Courtesy of the Martin Wong Foundation and P·P·O·W, New York

In the foreground of the painting at the base of the graffiti is a paragraph of floating hands recognizable as Wong’s signature ASL hand-letters that spell-out another stanza of poetry. The hands are transcribed in the painted wood-grain frame. So Wong lays out a visual code and decodes it for us, too. In “A Cosmos of Codes: The Languages of Martin Wong,” collected in Malicious Mischief (2022), Sofie Krogh Christensen notes, “considering the fact that ASL, like all sign languages, is not a written language and that all hearing-impaired persons write in the native hearing language of their country, Wong’s overtly graphic cartoonish ASL gestures hence remain predominantly pictorial for hearing and hearing-impaired alike” (Christensen 88). Suspending ASL over painted English (or in some cases, Spanish) poems and other written matter does not create a translation but it does enact a visual conversion that each viewer either reads or acknowledges the potential to read. In an essay titled, “Martin Wong Was Here” from Martin Wong: Human Instamatic (2015), Julie Ault puts words to my exact experience with Wong’s painting: “Attorney Street makes us think about language, multiple modes of expression, and their translatability–or lack thereof,” and later, “What are the relations between spoken and written language, sign language, graffiti language, pictorial language, the codes of painting, and so on, ad infinitum?”(Ault 86).

These passages by Christensen and Ault, published in separate essays nearly a decade apart, open up a line of questioning into the unique entanglement and entangled semiotics of language in the paintings of Martin Wong. What are Wong’s paintings doing to hybridize and queer the text that he renders in the cityscape? Does painting language—placing language in a pictorial context—fundamentally alter its sign value/function? And by converting text into image, does painting become an act of translation? Through Wong’s use of the ASL manual alphabet and its dialogic relationship to the English and Spanish verses he lifted from Miguel Piñero’s poetry (among other sources), I will argue that while translation is not literally happening in a this-equals-that sense, Wong’s unique example of painting text does transform, and by transforming language, is enacting a kind of visual translation between the mediums of text and image. By comparing Wong’s work to Chinese painting, we can see how he grafts traditions in pictographic language-art onto his multilingual alphabets, which I argue does more to encode language (and community) than it does to expose it.

In Madhu Kaza’s poetic essay, Lines of Flight, the author looks at an adaptation of Homer by the poet Alice Oswald as an example of language’s “ongoingness” and ability to transcend text (Kaza 14). A few key selections from Martin Wong’s œuvre channel this notion of ongoingness and will move a definition of translation toward interdisciplinary practice which is as likely to re-code as to reveal a given language.

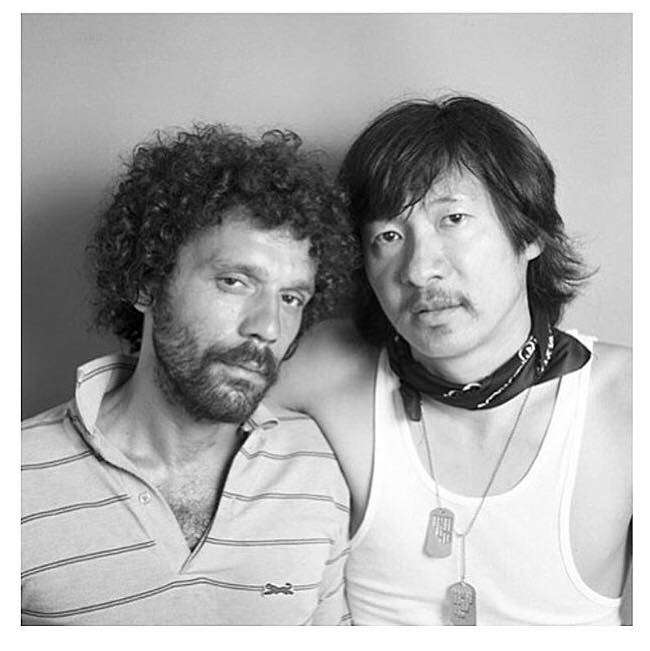

After Martin Wong’s death due to AIDS-related illness in 1999, post-mortem critical attention has often designated his paintings or the context of his artistry as a site of translation or metaphorical translation. In the catalog published for Wong’s groundbreaking retrospective at the Bronx Museum in 2015, Human Instamatic, Sergio Bessa employs “translation” to describe Wong’s position within US race relations in the fraught socio-political landscape of the 1970’s: “How Wong was able to participate in that pivotal moment in American culture can better be described as an act of translation through which he seamlessly merged his Asian heritage with the language of the American ‘white middle-class’” (Bessa 12). This sentiment is echoed by other art writers in their record of Wong as an outsider on multiple fronts: an outsider in New York, an outsider as gay and Chinese American in the predominantly latinx Loisaida, and an outsider artist painting against the popular grain of the art world at the time. Jon Yau puts it this way in his essay, “All the World’s a Stage, the Art of Martin Wong,” from Human Instamatic: “As an openly gay Chinese American man, Wong was considered an outsider in this neighborhood. However, instead of trying to hide his outsider status, Wong called attention to it by wearing a cowboy hat and shirt and sporting a Fu Manchu mustache. [Later] he taught himself Spanish and earned the nickname ‘Chino Malo’” (Yau 41).

Moving to New York in 1978, Wong’s relationship to the Lower East Side would be processed in paint. In the post-1975 fiscal crisis landscape, the Puerto Rican enclave was disproportionately affected by urban blight and crumbling infrastructure. Brick by brick Wong performed a visual record and rebuilding of his surroundings: the artist meticulously painted half-ruined tenements, outlined the chain-link fences, and detailed the detritus of abandoned lots. Wong constantly took photos of people and infrastructure to reference for paintings, bringing the very real local life directly into his narrative of the Loisaida. “Like the Nuyorican poets, Wong sought to disturb what Jacques Rancière calls ‘the distribution of the sensible.’ This is the way that subjects perceive ‘spaces, times, and forms of activity’ that allow them to understand the degree to which they share common goals, and inspires them to take part in governance,” writes Andrew Strombeck in his book, DIY On the Lower East Side (Strombeck 12). Included in Wong’s embrace of the impoverished environs was a particular attention to an almost apocalyptic aesthetic of urban entropy, as well as depictions of petty crime, the voices of drug addicts transcribed in poems, and incarcerated men in whited-out prison cells. Paintings like La Vida (1988), No es lo que has pensado (1984), and Stanton Near Forsyth Street (1983), exemplify this dual celebration and grim reflection of local figures in the brick theater of Wong’s world.

This positioning of the artist as visual historian, however, serves to reinforce the subliminal, if more anthropological, notion of translation as process or collateral of artistic practice. Translating what to what? A portrait of poverty into an artworld aesthetic? Or perhaps translation is a conceptual re-placement/re-coding device, a means to access and transcribe the multilingual, polyvocal community. Along these lines, I return briefly to Attorney Street: Handball Court with Autobiographical Poem by Piñero, which exemplifies the imbricated dialogic life of the neighborhood where voice is traced in poetry, yes, but also in the traces of graffiti which render the walls of the neighborhood palimpsests of local writers shouting their names in aerosol. The ASL manual alphabet seems to do its own thing, or some connective thing, in this piece, floating above and about the graffitied court like kufic script on air. In an essay from the 2023 publication Martin Wong: Malicious Mischief, the curator Agustín Pérez Rubio writes that, “[Wong] translates to painting concepts and ideas, which he had previously developed in his poems, relating to the notion of creating a choral language as a way to research community and to reflect upon and understand himself, but also as a way to create his paintings with sign language” (Rubio 132). In a different ode, Portrait of Miguel Piñero, Piñero’s portrait is rendered in the low foreground of the scroll-shaped painting. Buildings layer the background with a few glowing yellow windows, echoing some of the hands which completely fill the greenish-black night sky. The yellowy hands float amidst dark brown hands and in well-crafted rows of deaf-lettering, they encode a poem.

By his own retelling in a 1984 interview with Yasmin Ramirez, Wong came upon the impulse to paint hand-signs spontaneously on the chance encounter with a deaf-mute in the subway who was passing around cards with the illustrated American Manual Alphabet. The stylized lettering, however, would become his trademark, and by 1980 his first “paintings for the hearing impaired came into being” (Yau 39). In the case of Portrait of Miguel Piñero, the hands spell out the first verse of Piñero’s famous dirge, “A Lower East Side Poem,” thereby transcribing (as opposed to translating) Piñero’s words: “Just once before I die / I’d like to climb up / to a tenement / sky and dream my / lungs out till I cry / then scatter my / ashes thru the / lower east side” (Piñero 4-5). By rendering the poem in the manual alphabet Wong does two main things: he codifies the language pictorially and in doing so, he converts the text into image. This transmutation of text into text-image is not an alteration of legibility necessarily, but it is a reimagining of word form that redirects our ability to read. Hand-signs as code become a buffer that slow the viewer’s entry into the language, participating in that disturbance of “the sensible.” Sofie Krogh Christensen describes the effect: “The time it takes the viewer to connect the Latin letters and ASL delays and thus disturbs the sign’s semiotic system, setting it apart from the structuralist rules of language. Instead of affirming a certain inherent semantic structure, Wong’s gesturing hands traverse the realm of the more animated pictograms, icons, and codes” (Christensen 88). The hands communicate the way graffiti communicates based on an in-culture of style and privacy. Floating amongst Spanish and English and sometimes graffiti, Wong’s hands are a common denominator of language within his œuvre, but as a painterly code, they also act to stall legibility.

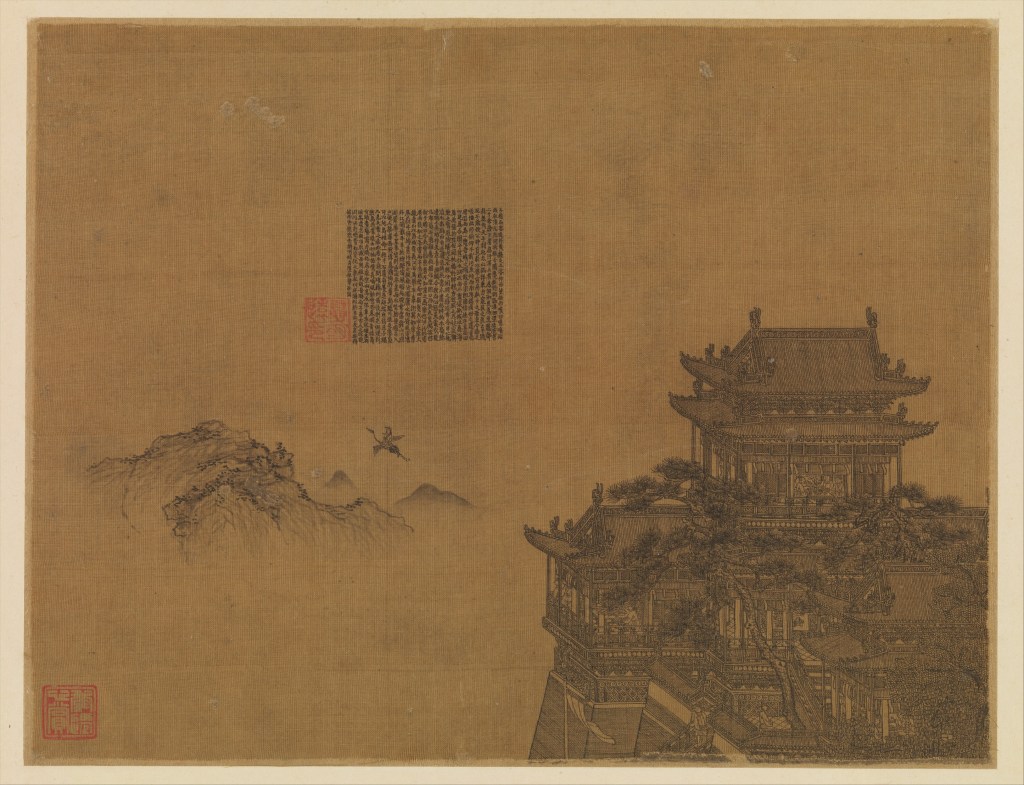

Xie Yong (active second half of 14th century)

Where does the writing begin?

Where does the painting begin?

Roland Barthes, Empire of Signs, 1983.

In an often-quoted moment from that 1984 interview, Martin Wong told Yasmin Ramirez, “Basically, I’m a Chinese landscape painter. If you look at the Chinese landscapes in the museum they have writing in the sky. They write a poem in the sky and so do I” (Ramirez 109). While Wong was known to have drawn influence from myriad spheres of art history, this is the only acknowledgment of Chinese landscape painting as a resource (as well as a tradition) that Wong identifies with. Poetry, painting, and calligraphy, are valued for their formal unity in the Chinese landscape tradition and Wong apparently took particular inspiration from Sung dynasty artists and their influence on subsequent generations of Chinese landscape painters. In the introduction to Words and Images: Chinese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting, author Alfreda Murck cites scholar Xie Zhiliu, who analyzes Sung dynasty landscapes, noting “the relationship between painting and poetry as one of a shared ‘visual thinking,’ and concludes that the two arts proceed from the same intellectual focus and emotional experience” (Murck xv-xvi). The character-based, pictographic nature of Chinese writing makes this formal unity between painting and poetry cohesive, perhaps even intuitive in a way that alphabetic writing systems would not (and generally do not or cannot) produce. Roland Barthes adds to this sentiment in his essay, Empire of Signs (trans. by Richard Howard), expanding on his point that painting has a “scriptural as opposed to expressive origin.” Speaking from a French perspective on a speculative Japanese culture, Barthes erases the division between painting and writing:

The theatrical face is not painted (made up), it is written. There occurs this unforeseen movement: though painting and writing share the same original instrument, the brush, it is still not painting which lures writing into its decorative style, into its flaunted, caressing touch, into its representative space (as would no doubt have been the case with us––in the West the civilized future of a function is always its aesthetic enoblement); on the contrary, it is the act of writing which subjugates the pictorial gesture, so that to paint is never anything but to inscribe (Barthes 21).

Wong and Barthes in their own ways introduce that distinction between Western and Eastern conceptions of the painting/writing binary. By associating explicitly with Chinese landscape traditions, Wong is grafting a pictographic sensibility onto a New York cityscape and Latin alphabet. From another POV, Barthes lays out the assumed and historical divide in Western art history, which has charted distinct paths for the mediums. Text, as it is deployed in Western painting traditions, tends to perform a didactic function as label or scripture rather than a structural function which would make the text itself pictorial and simultaneously sentimental. Re-looking at Attorney Street, or Portrait of Miguel Piñero, Wong’s innovative use of sign-language and transcription of graffiti art is to think of painting in a role-reversal with writing. Or to put it another way, perhaps a reverse ekphrasis by crafting an image that converts Piñero’s words to the picture plane; converts graffiti to permanence.

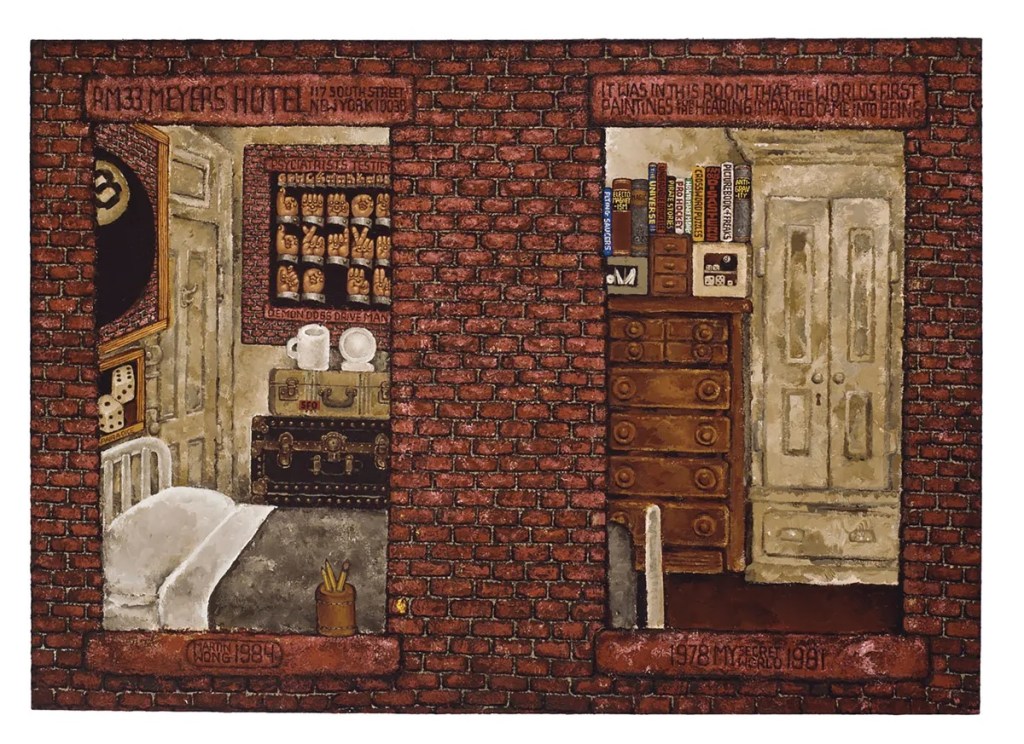

To paint English or Spanish language, to paint bilingually, is not in and of itself new to the Western painting tradition but it is innovated by Wong’s equal treatment of the ASL manual alphabet and graffiti—two visual languages—which foil the English and Spanish as points of immediate legible narrative, ports of entry into the composition. He spells the painting and images the language. And to further define Wong’s innovation, the artist not only converts an alphabetic language to a pictorial domain, but in that conversion assigns functions to each language that cues narrative devices which sublimate that tension of the partly opaque, partly see-through environment. In a seminal work depicting the artist’s room in the Meyers Hotel, My Secret World 1978-81, Wong positions the viewer outside the brick façade, looking in on his collection of books and ASL paintings through two windows. This painting, which historicizes the room where the first manual alphabet paintings were developed, assigns exactly that half-guarded dynamic with the viewer. Jon Yau writes in his essay for the publication of Human Instamatic, “By turning viewers into voyeurs, the artist emphasizes that looking is not innocent, and that there is no such thing as an innocent eye, rather, there is a gap (or partial barrier) between the viewer and viewed. Wong is positing a dilemma between telling and withholding, which lives at the heart of all art” (Yau 38).

The physical opacity Wong builds-up in paint (think also of Wong’s storefronts and buildings where the windows are bricked-in), he echoes through language as code. Jon Yau further reads into the development of the manual alphabet motif as evidence of Wong’s recognition that “art, no matter how accessible, is not universal. In fact just the opposite–art must always be deciphered and interpreted.” So Wong guides the poetry of collaborator/poet Piñero, headlines, and Spanish comic book dialogue into a privacy shaped by conversion across mediums, supplemented by imagery of twinkling astrological star maps, and destitute, lovelorn figures in the eroded cityscape. The painted space problematizes the presumptive function of words to be read, creating an image out of language, and demands that the viewer decipher the image to get through it.

Copyright Martin Wong Foundation

Courtesy of Martin Wong Foundation and P·P·O·W, New York

Say anti-translation as not refusing to translate, just refusing to translate. Refusing to translate, like this. Say it again.

Say I’ve never heard someone divulge so much of their personal intimate life only to claim that their politics are private, say coded language, say language is code.

Say translation of private space.

Sawako Nakayasu, Say Translation is Art, 2020

Somewhere in the carrying over of language into image, in the influence and redeployment of a Chinese landscape’s poetry in painting/painting in poetry, or in the codified hand-signs floating over the Lower East Side, something very close to translation is happening. Martin Wong becomes an accidental moodboard of multilingual imagery by complexifying the role of text and reforming it compositionally within paint; by recording and re-coding a polyvocal culture in a cluster of imbricated imagery; by not translating the languages; by creating opacity through new codes. The painting becomes a site of interlingual cohabitation, allowing for the same surface image to simultaneously be more legible to more people, while creating the opportunity to exclude viewers who do not read in Wong’s painted languages. Paintings like Attorney Street, therefore, include and exclude with a targeted opacity that encodes the subjects, revealing only superficially what was essentially the record of a surviving marginalized community.

In Poetics of Relation, translated by Betsy Wing, Édouard Glissant articulates the opacity inherent to literature—the paradox of literature as generator of opacity through the act of writing:

Because the writer, entering the dense mass of writings, renounces an absolute, his poetic intention, full of self-evidence and sublimity. Writing’s relation to that absolute is relative; that is, it actually renders it opaque by realizing it in language. The text passes from a dreamed-of transparency to the opacity produced in words (Glissant 115).

In painting, Wong seems to take this point a step further even, first by dissolving the boundary between text and image, which contrary to accessing that “dreamed-of transparency,” adds a literal opacity to the new materiality of language. Through thick, acrylic paint, Wong imbues the language with physical properties, giving it dimension and surface area. Secondly, as we’ve been exploring, Wong found a code through which to render alphabetic language as letters that are also images, forging an opaque iconography that can be left mute as hands, or can be literally read by the viewer.

Painting the manual alphabet is a form of transcription because each hand sign is designed to articulate a letter, so the equation is a one-to-one transference of a Latin alphabet into a manual alphabet. Transcription and not translation because there is no interpretation, no loss of linguistic nuance or need to carry over a force from one language into another. There is, however, a profound change and a reconfiguration of the language as it’s represented, even, an invention of script that in any other setting, serves a completely different function. To repeat Sofie Krogh Christensen’s point from her essay in Martin Wong: Malicious Mischief, “ASL, like all sign languages, is not a written language.” Perhaps this invented representation does do something to the meaning of the words even if it’s not a translation. So in Attorney Street, the 75 floating hands paint a new voice, Wong’s errant cipher, which, like connective tissue, bridges the conceptual gap between the visual languages of painting, graffiti, and the written languages of poetry and headlines.

Glissant, in his definition of errant, could be psychoanalyzing Wong, the outsider whose paintings synthesize and redeploy a whole cultural mood like a dispatch from Loisaida. Despite his position as fixture in the neighborhood, Wong maintained his aesthetic perspective on the margins of LES community, allowing him to observe and romanticize. To exist in erosion and beautify as a poet. Glissant writes,

[O]ne who is errant (who is no longer traveler, discoverer, or conqueror) strives to know the totality of the world yet already knows he will never accomplish this–and knows that is precisely where the threatened beauty of the world resides.

Errant, he challenges and discards the universal–this generalizing edict that summarized the world as something obvious and transparent, claiming for it one presupposed sense and one destiny. He plunges into the opacities of that part of the world to which he has access (Glissant 20).

Considering Wong in this light at first seems to corroborate Sergio Bessa’s notion of Wong as the outsider-guide consumed by the wealthy white art world to get a glimpse of the raw life of the LES as depicted in Wong’s art. On the contrary, this errantry means that Wong is a scribe that commits imagery to opacity rather than transparency. He does this literally, by layering the painted scene in view-obscuring walls of brick, bricked-out windows, and skies full of hand-signs, star-signs, and poetry; he does this metaphorically, by lacing his paintings with codes and language that reference the pictograph calligraphy in Chinese landscape paintings.

Can we call this inverse translation? Anti- or non-translation?

By painting, Wong permits limited access into a psycho-social corner of New York whose architects are the poets, graffiti writers, and drug addicts that each take part in mystifying their own legacies. On the one hand, like the imagined Japan in Roland Barthes’ Empire of Signs, Wong depicts a fictional Loisaida and leverages its features to explore an original vision. In this sense, he very much echoes Barthes’ opening passages on Japan: “To me the Orient is a matter of indifference, merely providing a reserve of features whose manipulation—whose invented interplay—allows me to ‘entertain’ the idea of an unheard-of symbolic system, one altogether detached from our own”(Barthes 3). On the other hand, Wong’s symbolic system (which we can call the interplay of languages and manual alphabet as an easy code) is drawn from an opposite relationship to that fiction. Whereas Barthes was an outsider imagining a theoretical platform for doubling a foreign culture and analyzing its symbolic qualities, Wong was charged by a deeply involved and romantic relationship to his source material, implicating not only himself in the social environment but also real stories, headlines, and local voices. Wong is symbolizing through an errant gaze, one that maneuvers the influence of pictographic language to make the voices around him a material reality and in doing so, exemplifies a material challenge to language as well as to the insider/outsider binary.

In the notes to Glissant’s definition of errantry, translator Betsy Wing writes, “Errance for Glissant, while not aimed like an arrow’s trajectory, nor circular and repetitive like the nomad’s, is not idle roaming, but includes a sense of sacred motivation.” With the connotation of this sacred motivation in mind, Wong’s in-betweenness exerts an influence on the languages he adopts into imagery that roots them in multitudinous interpretation, complicating the possibility and even the desire to translate. What I mean is that we can no longer ignore his identity completely, but instead of psychoanalyzing the artist, I put forward that his unstable role within the social fabric of his community begets a rhizomatic gaze that allows for meaning to be transferred without being translated and alternatively, for language to be conveyed in a way that buffers meaning. The way this plays out depends on the painting, but for the purposes of this essay, I turn to Attorney Street one more time.

What do the hand-signs spell out?

When employing the manual alphabet, Wong either gives us their language in the title or in another inscription somewhere else in the body of the painting. In this case, meticulously rendered language enters at every tier of the painting, from the trompe l’œil wood frame which is depicted to be carved-into with the manual alphabet, the trompe l’œil plaque (frame within the frame), to the poetry in the sky, the wall of graffiti, the hand-sign paragraph, and then more text carved into the bottom rim of the wood frame. As is typical in Wong’s paintings, the hand-signs mostly parrot the English text and that is their entire function. The trompe lœil plaque along the top of the composition reads “AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL POEM by PIÑERO • ATTORNEY STREET HANDBALL COURT 1982 • RENDERED IN PAINT by MARTIN WONG.” At the top of the frame, the hand-signs reiterate the language excepting some words: “Attorney street handball court by Martin Wong.” A similar operation happens at the bottom of the canvas but in that example, the paragraph of hands do not miss a single letter, echoing: “ITS THE REAL DEAL NEAL / IM GOING TO ROCK YOUR WORLD / MAKE YOUR PLANETS TWIRL / AINT NO WHACK ATTACK.”

Courtesy of the Martin Wong Foundation and P·P·O·W, New York

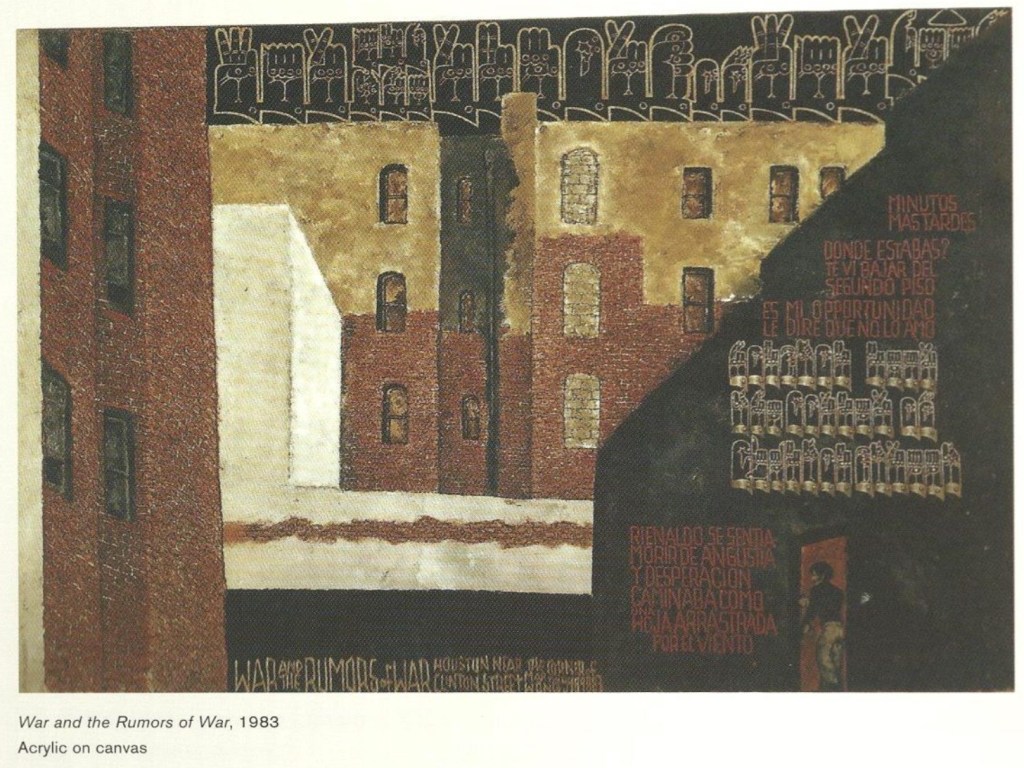

A painting from 1983 shows a slightly different operation happening. In the case of War and the Rumors of War, Wong depicts a figure modeled off Piñero in the foreground of a dark wall slipping into a glowing red doorway. The entire canvas is blocked out with brick and building façades, overlapping and crowding the airspace: there is indeed no room for natural things in this vision of New York and just like his other works, the sky is choked with gilded hand-letters. On the bottom of the picture Wong paints in yellow the title, the cross street, his name and phone number: “WAR AND THE RUMORS of WAR HOUSTON NEAR THE CORNER of CLINTON STREET MARTIN WONG 5989883.” This text is doubly encoded in the sky and again on the silhouetted angle of the building where Piñero is slipping into a doorway. About and below those painting hand-letters which mimic the location, Wong renders text in Spanish that describes the action of the painting:

“MINUTOS MAS TARDES / DONDE ESTABAS? / TE VI BAJAR DEL SEGUNDO PISO / ES MI OPPORTUNIDAD / LE DIRE QUE NO LO AMO /

REINALDO SE SENTIA / MORIR DE ANGUSTIA / Y DESPERACION / CAMINABA COMO / UNA HOJA ARRASTRADA / POR EL VIENTO”

Wong does not translate these words into English nor transcribe them into ASL. He leaves them as they are. You get it or you don’t.

What may come through for the non-Spanish reader is the positioning of the language in an angular descent down the silhouetted wall which, overlapping with the hand-letters that denote the street corner, and encroaching on the lone, absconding figure, emote a movement of narrative and maybe a sentiment. Do they still convey, on some level, regardless of intelligibility? Maybe I can’t say; as a Spanish speaker and reader, the words are legible to me, but might presume that in their ordering, the small groupings of words and organization in proximity to an action, they still suggest something. Examples like this in Wong’s œuvre beg the question of what we expect of language when it’s put in front of us and perhaps the implicit expectation of language to always cater to the majority ability. In the US, Spanish would be considered a minor language (at least in the literary sense: see Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, 1986.) and therefore, almost obligated to be translated when presented to a general public. This brings me back to Sawako Nakayasu’s lines in Say Translation is Art. When she writes, “Say translation of private space,” Nakayasu is denoting something along the lines of Glissant’s right to opacity and Wong’s utterly honest specificity; the specificity being Wong’s relationship to Spanish as an insight in his love of Loisaida and his muse, Piñero.

The translator Madhu Kaza brings Nakayasu’s questioning of translation right into the paradox of the word itself. In Lines of Flight, Kaza deploys a quote by the scholar Mini Chandran to consider the instabilities of translation by juxtaposing translation’s latinate roots with the word itself in translation across several Indian languages,

The word ‘translate’ comes from the Latin ‘translatio’ where ‘trans’ means across and ‘latus’ means carrying; the word thus means the carrying across of meaning from one language to the other. The various Indian language words for translation do not convey this meaning. Anuvad (speak after), bhashantat (linguistic transference), tarzuma (reproduction), roopantar (change of form), vivartanam (change), mozhimattam (change of script) (Kaza 25).

It is important to remember that translation itself is a word that re-forms and mutates dependent on its function: to translate “translate,” carry the word itself over into new languages and cultural contexts, we encounter equivalences that necessitate change, and so the source itself changes, with the new language superimposing a slightly altered meaning in retrograde, or in circularity. If we can speak with translation in mind as not a one-fixed thing but a passenger within the currents of myriad interpretations, its function becomes context-dependent and rhizomatic, which is to say, on the move depending where it is needed. Madhu Kaza and Sawako Nakayasu both illuminate the malleability of definition by applying that to the meaning of translation itself. In doing so, they help clarify that translation is often something like translation and not necessarily that lateral transference from one written language into another. Kaza’s citing of Mini Chandran’s words in particular reveals the fallacy of isolating translation to monosemy. In the case of language in Martin’s Wong’s paintings, translation is at work, but often it’s up to the viewer to do the translating and where they choose not to or cannot, the language is image and the image is paint.

Copyright Martin Wong Foundation

Courtesy of the Martin Wong Foundation and P·P·O·W, New York

Photo: Tom Warren

References

Ault, Julie. “Martin Wong Was Here.” Martin Wong: Human Instamatic (Black Dog Publishing, 2015) 83 – 90.

Barthes, Roland. trans. Richard Howard. Empire of Signs (Hill and Wang NY, 1983.)

Bessa, Antonio Sergio. “Dropping Out: Martin Wong and the American Counterculture.” Martin Wong: Human Instamatic (Black Dog Publishing, 2015) 11 – 25.

Christensen, Sofie Krogh. “A Cosmos of Codes: The Languages of Martin Wong.” Malicious Mischief (Walter Konig, Köln. 2022.) 82 – 98.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix, trans. Dana Polan, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (Univ. Minnesota Press, 1986.)

Glissant, Édouard. trans. Betsy Wing, Poetics of Relation (Univ. Michigan Press, 1997).

Kaza, Madhu H. Lines of Flight (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2024).

Murck, Alfreda. Words and Images: Chinese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting (Princeton Univ. Press, 1991.) xv – xvi.

Nakayasu, Sawako. Say Translation is Art (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020.) 2.

Piñero, Miguel. “A Lower East Side Poem.” Outlaw: The Collected Works of Miguel Piñero (Arte Público Press, 2010.) 4-5.

Ramirez, Yasmin. “Chino-Latino: The Loisaida Interview.” Martin Wong: Human Instamatic (Black Dog Publishing, 2015.) 109 – 121, 109. Note: This quote is actually from a previous interview conducted in 1984 for the East Village Eye. I have had a hard time sourcing that interview but Ramirez recycles the quote here in the introduction to this interview from 1996, just three years before Wong’s passing.

Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill, Bloomsbury Revelations (London : Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 12.

Rubio, Augustín Pérez. “…it’s not really what you think: Martin Wong and the Recreation of the Sociopolitical Landscape of Loisaida.” Malicious Mischief (Walter Konig, Köln, 2022.) 130 – 156.

Strombeck, Andrew. “Chapter 2: The Puerto Rican Working Class and the Literature of Rebuilding.” DIY on the Lower East Side: Books, Buildings, and Art After the 1975 Fiscal Crisis (SUNY Press 2020) 55 – 83.

Yau, Jon. “All the World’s a Stage: The Art of Martin Wong.” Martin Wong: Human Instamatic (Black Dog Publishing, 2015) 37 – 48.

Yong, Xia. The Yellow Pavilion, album leaf, ink on silk, ca. 1350. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and seen in: K. Hearn, Maxwell. How to Read Chinese Paintings (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008.) 92.

Addison Bale (1994) is an artist and writer based in Brooklyn, born and raised in NYC. His paintings have been discreetly featured around town and most recently in Mexico City (Feb, 2025). Bale’s poems and/or translations have been included in DiSONARE 09 (MX) (2023), Everybody Press issue 03 (2023), No Dear issue 25 (2021), Michigan Quarterly Review (2021). A collection of poems in Spanglish, GALIMATÍAS, was printed by The Lab Program, Mexico City, 2022.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, March 25, 2025