Like a Simile: Creative Translation and Alice Oswald’s Memorial

by Zeynep Özer

This, then, is the task of the creative translator. As she charts a meandering course between the languages, making unexpected stops, she uncovers latent energies and new possibilities that slowly begin to take root.

My first translations of poetry were a little lopsided. Each line I translated from Turkish would be accompanied by a small paragraph reflecting on what I understood from it, the choices the poet made, and how I might go about recreating those choices in English. An utterly impractical approach for launching a prolific career in translation, yet these reflections helped me slow down what seemed like an enigmatic process and find ways to be more intentional when traveling between languages. If translation is essentially the act of taking “stuff”—words, tone, rhythm, meaning, stylistic nuances—from Language A and rendering them in Language B, what we do is clear enough. It’s the how, however, that is the real head-scratcher. How does a minute gesture, a slight change in tense, for example, alter the entire meaning? How does one choose to make that slight change, even if it means letting go of all the other possibilities?

My tiny reflections—my annotations—gave me a chance to sit with each line and slowly unravel its potential. They allowed me to put into words my interpretation of the poem, my process, and the choices I made. In a way, these notes became a personal space where I could engage with the poem, conveniently situated alongside the more final translation draft. The result often resembled an annotated translation, almost like a personal essay about the process—an extended translator’s note of sorts. This approach helped me settle into more consistent methods and develop a deeper understanding of the intuitive choices I made, both as a translator and as a reader.

Those early translations gradually evolved into a more deliberate creative exercise, a hybrid form that blended writing with translation, an excellent tool for developing effective translation techniques. As many brilliant translators have demonstrated, creative translation offers an opportunity to lift the veil on meaning—both in the original text and in the translation—and to peek not only at what is said, but also what remains unsaid in both languages.

One such translator is Alice Oswald, whose Memorial (2011) shows her extraordinary ability to intervene precisely at moments of silence in the source text. The result is a beautiful poetry collection that doubles as a work of creative translation, one that can serve as a model for translation practices.

The collection’s subtitle, A Version of Homer’s Iliad, along with the roughly ninety pages that follow, cues the reader into Oswald’s idiosyncratic approach to one of the most well-known and widely translated texts in history: the Iliad. In her preface, which functions as a translator’s note, Oswald clarifies her intentions, calling Memorial “a translation of the Iliad’s atmosphere, not its story” (ix). What we’re reading is unmistakably Oswald’s version of the Iliad. Yet, as she admits, it is “a fairly irreverent translation” (x). She’s retrieving something less tangible than the words, syntax, or meter of the epic from the classical Greek; she’s translating its “enargeia,” or its “bright unbearable reality” (ix). Her self-confessed irreverence is specifically directed at the narrative, taking it away much like “lift[ing] the roof off a church in order to remember what you’re worshipping” (ix). She strips away what we might consider the fundamental, foundational aspects of the work in order to look at what the load-bearing walls—its form—encapsulate: the lives lived within. Oswald’s long poem intertwines the biographies of every so-called minor war casualty in Homer’s epic with unique twin similes that juxtapose nature and daily life against the violence and death wrought by war.

These biographies and similes all liberally draw from Homer’s original words. In her dedication to conveying the atmosphere rather than the story, and in adopting an “irreverent” approach to the original, Oswald delivers what might be called a creative translation of the Iliad. Rather than sticking closely to the word of the text, she focuses on the glaring reality of war. In conventional terms, this reality is her source language. The omission of the narrative gives her the license to take advantage of everything that has been said or unsaid in the epic.

For instance, where the Iliad is both a celebration of and lament for the sufferings and victories of men in war, Oswald’s version recognizes the women behind those laments. Elephenor, who is only the “son of Chalcodon” (his father) in the original, becomes a son to his mother as well, even if “nothing is known” of her (Oswald 10). Caroline Hahnemann claims that, by conveying “information about the dead man’s mother,” Oswald “undermines the patriarchal perspective” of the original, which overlooks the mourning mother and speaks only of the father, and turns “the silence of the ancient epic into words” (95). As Oswald translates the absence of the mother in Homer into words, she doesn’t add any information that we don’t find in the original—then and now we still know nothing about Elephenor’s mother, Chalcodon’s wife, the unnamed woman. And yet, by taking advantage of the text’s silence, Oswald finds a way to convey the “bright unbearable reality” (ix). Even in their grief for the hero, the women of the Iliad remain condemned to anonymity and silence—unless, or until, a creative translator like Oswald brings them into the light.

Facing the text’s silence and wielding an absolute poetic license, Oswald discovers an alternative place to be. It’s akin to what poet, classicist, and translator Anne Carson calls “a third place” in her hybrid poetry-criticism essay, Nay Rather (26). Carson identifies this third place as somewhere “between chaos and naming” and describes what it’s like to be there: “In the presence of a word that stops itself, in that silence, one has the feeling that something has passed us and kept going, that some possibility has got free” (26). The translator who latches onto the feeling of an elusive meaning searches for solid ground. This search is a dialectical process: chaos involves a proliferation of meaning—a quality we might associate with poetic expression—while naming seeks precision and containment. Translation, often straddling this dialectical tension, offers “a third place to be,” marked by presence or absence (26). I use “marked” intentionally, as the presence (signaled by a word) or absence (signaled by silence) already suggest an event: something has taken place in the interpretive process. What the creative translator does is restate—or state—that event in her words.

In other words, the creative translator attempts to grasp the “possibility [that] has got free” (26). She holds onto it just long enough to collect its energy, repurpose it, and channel it into the translation. This “third place” where these possibilities thrive may well lie between the untranslated and the so-called faithful translation, which seeks the impossibly perfect equivalence between languages (26). On this alternate ground, the interpretive process aims to make space for meaning to travel between the source and the target languages. Essentially, the translator’s interpretation allows the connective tissues between these languages to breathe. As Walter Benjamin puts it in his famous essay “Task of the Translator,” “translation ultimately has as its purpose the expression of the most intimate relationships among languages” (77). For a translator, the most generative possibilities arise from recognizing that the relationship between languages—and by extension, the source text and the translation—is not static. Instead, all the elements and connections that create this intimate relationship form a dynamic network that might engender multiple possibilities.

To access these possibilities, a translator should first see the translation process as it is: not a linear equation, but a careful balancing act between various and scattered touch points. The translator who approaches the text creatively would then try to stray from the conventional, linear line extending from language A to language B. Writer and translator Harry Mathews points out that, because we tend to focus solely on making sense of what we read, what might seem like “cavalier” acts by a creative translator are in fact “useful in drawing attention precisely to elements of language that normally pass us by” (71). In this context, the straightforward meaning of words, or their “nominal sense,” becomes just one part of the overall meaning (71). The “nominal sense,” which corresponds to the narrative (“the story”) in a work like Memorial, is only one component of the broader meaning-making process. Each building block of this process “can be isolated and manipulated” to highlight what usually passes us by—what emerges as presence or absence in the interpretive process (71). This, then, is the task of the creative translator. As she charts a meandering course between the languages, making unexpected stops, she uncovers latent energies and new possibilities that slowly begin to take root.

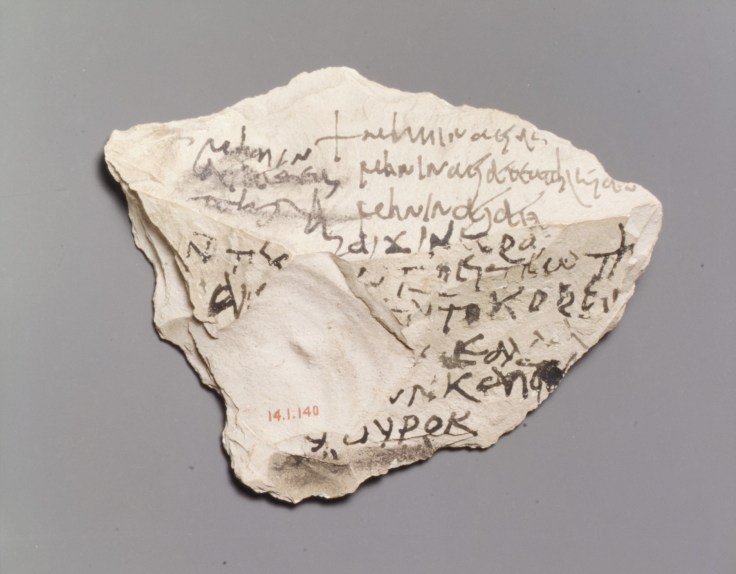

Anne Carson’s Nay Rather isn’t just a treatise on the interpretive process; it also illustrates the mechanics of the creative translator’s task through the wondrous poem “By Chance the Cycladic People.” Carson’s theory (the essay) and her practice (the poem) sit side by side, facing each other on the page. Especially at first encounter, the poetic sequence seems daunting. It’s a procession of randomly ordered lines, or rather, fragments, about the Cycladic culture, a Bronze Age civilization that flourished in the Aegean Sea. Carson, a classicist, is celebrated for her translations of Sappho’s fragments, and here too, she’s clearly drawn to the fragment as a form for its capacity to convey meaning in isolation and in accumulation. Even if these fragments are separated from a larger whole, their presence on the page is telling. A reader who spends enough time with them will begin to develop a certain fascination with and regard for what they might reveal, precisely because they are fragments. After all, they are a mysterious collection of words about an ancient culture.

This mystery inspires a narrative desire in the reader or viewer, much like Lanfranco Quadrio’s drawings, which accompany Carson’s words and are inspired by her text. We are naturally driven to connect the dots, complete the missing information, and search for some kind of plot. Carson acknowledges this desire herself when she reminds us in the essay that “humans are creatures who crave story” (14). Reading Carson’s work often becomes an experience of craving connections while also learning to let go, transforming our desire for narrative into a meta, self-reflexive part of the reading process. We start to think about our desire for narrative and linearity, and how this desire is complicated at every turn, with every fragment, line, or image.

While the collection of fragments prompts self-reflection on our desire for story, their disunity draws our attention to each individual line. Each fragment becomes an occasion to look at and celebrate the world contained within it. Each boldly asserts its own authority, as a piece potentially complete in its aesthetic identity. And this is one explanation for Carson’s fascination with Cycladic culture and their sculptural figurines, found in tombs and characterized by distinct, flat, schematic styles. Together, they clearly form a larger story, serving as celebrations or narrative attempts to capture a life lived and lost; yet each one stands as an autonomous work of art with its own individual expression and sculptural grace. Carson’s poetic sequence recreates this experience. It provokes in us a desire to spot connections and feel the looming presence and availability of narrative, while also training our aesthetic awareness to appreciate the craft and possibility contained in each individual section. Absence and presence drive the desire for narrative and aesthetic pleasure, as they do in the interpretive process of the translator.

Similarly, in Memorial, Oswald taps into this interpretive process. As she plays with absence and presence, she isolates—and celebrates—the Iliad’s formal features, bringing out the possibilities that exist in the dynamic web between languages. Notably, in a move echoing Carson, Oswald does away with the narrative. Given the Iliad’s historical and cultural weight, this alone is a dramatic move, nudging us to examine our attachment to the narrative that, in the original, subsumes actual human lives. These lives are placed front and center by the monumental catalog of the dead at the beginning of Memorial, which follows the sequence of events in the Iliad and unmistakably links the poem to the epic. However, as Caroline Hahnemann notes, it also evokes monuments of war, “most notably Maya Lin’s famous Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC” (91). Indeed, the title of Oswald’s book is no accident: much like Lin in her own work, Oswald memorializes and monumentalizes the individuals who became numbers or negligible details in the story and aftermath of war.

In doing so, Oswald also manipulates the nature of epic poetry: without the story, an epic becomes a lyric. She essentially recasts the Iliad in a new form, translating it into a lyric poem. Or, more accurately, she excavates the lyric lying silent within the epic, rebuilding from these findings “a bipolar poem made of similes and short biographies of soldiers” (Oswald ix). Her careful reading unveils traces of “the Greek tradition of lament poetry” in the biographies of the fallen soldiers and unearths pastoral lyrics buried in Homeric similes: “you can tell this because their meter is sometimes compressed as if it originally formed part of a lyric poem” (Oswald ix). As she explains the sources she drew from, Oswald reveals another crucial layer of the translation process. Her translation isn’t just about transmitting words from one language to another but, as is true for any good translator, it’s informed by her knowledge of the context behind the text. As a classicist, she’s making educated guesses, reading between the lines and into the history to excavate and retrieve the silent material she foregrounds in her version.

The translator’s note establishes the context for Oswald’s version not as an isolated epic, but as a work shaped by the sociopolitical and cultural background that gave rise to it. Georgina Paul points out that, through this translator’s note, Oswald offers the reader “a space for thinking about the Iliad differently, as a poem constituted from different kinds of sources and rituals rather than as an epic whole” (147). In fact, part of Oswald’s way of listening to the Iliad involves overhearing those formal features that pulse through the text, tracing its various gestures back to ritual forms and laments, cultivating an intuitive attunement to traditions tied to women’s bodies and voices. She explains:

When a corpse was laid out, a professional poet (someone like Homer) led the mourning and was antiphonally answered by women offering personal accounts of the deceased. I like to think that the stories of individual soldiers recorded in the Iliad might be recollections of these laments, woven into the narrative by poets who regularly performed both high epic and choral lyric poetry. (ix)

In Oswald’s version, the epic glorification of heroic deeds and the mourning of war heroes become a lyrical celebration of the individual and a lament by their loved ones—:“an attempt to remember people’s names and lives” (x). Paul rightly argues that by recreating the rituals of mourning, Oswald foregrounds “a social practice traditionally associated with women” and “reinstates it by highlighting its presence as one element among many within the organizing line of Homer’s epic narrative” (152). As Oswald balances her version on the lament—one of many elements of Homer’s epic—women reclaim a space in this outwardly male world through her translation (which, though different, isn’t altogether dissimilar to Emily Wilson’s recent translation of the Iliad).

For Oswald, the original text, the Greek words, become “openings through which to see what Homer was looking at” (x). Through these openings, she sees mothers, daughters, and wives suffering the loss of many young men who died in passing, whose deaths are barely acknowledged in the Iliad, overshadowed by the glorious deeds of epic heroes. Oswald describes her approach in this work as “aiming for translucence rather than translation” (x), and I understand this claim of translucence as an act of creative translation—one that offers a glimpse into the unsaid and foregrounds the absent, rather than adhering to a conventionally “faithful” translation. Of course, the concept of “faithful” translation is a problematic one, often used to uphold certain hegemonic ideals. In The Translator’s Invisibility, Lawrence Venuti argues that “canons of accuracy in translation, notions of ‘fidelity’ and ‘freedom,’ are historically determined categories,” entirely dependent on power relations (18). Emily Wilson, translator of the Iliad (and the Odyssey), echoes this in “Translating Homer as a Woman,” noting that the metaphors often used to describe translation “in terms of fidelity or infidelity, as well as origin or parent, versus the copy or the child—are implicated in androcentric, heteronormative ideas of family structure” (280).

Finding the third place where the textual and contextual possibilities can live requires the translator to actively interfere with the text, to deconstruct and reconstruct it in a way that speaks to a new audience and context. In her foundational essay “Theorizing Feminist Discourse/Translation,” Barbara Godard frames this requirement (or necessity) in relation to feminist discourse and feminist translation, though her ideas undoubtedly extend to other ideologies that impact the translation process. According to Godard, the work of translation can and must produce “an estrangement effect or defamiliarization” to disrupt the status quo: “Although framed as a transfer from one language to another, feminist discourse involves the transfer of a cultural reality into a new context” (22). This is precisely what Oswald does: she translates the habitual form—the epic—into the unfamiliar lyric, and (re)asserts the cultural reality of the silent and neglected men and women. Yet, her method of disruption and defamiliarization isn’t untethered from the Iliad’s methods of composition, as she acknowledges that her interpretive process is rooted in “the spirit of oral poetry, which was never stable but always adapting itself to a new audience, as if its language, unlike written language, was still alive and kicking” (x). She looks at the foundations and the building blocks of Homer’s epic and finds possibilities that can speak to a new audience and context today.

In this way, the contemporary world becomes what Harry Mathews terms the “home ground” for a writer who, like a translator, is writing from and within a specific context. Mathews says, “Think of the writer’s object of desire—vision, situation, whatever—as his source text. Like the translator, he learns everything he can about it. He then abandons it while he chooses a home ground. Home ground for him will be a mode of writing” (78). For Oswald, who is already well-versed in this classical text, her home ground lies in the sociopolitical landscape of the twenty-first century. This context surrounds Memorial, which was written concurrently with the wars and military interventions of the early twenty-first century, events that swallowed up individual casualties into narratives framing violence as necessary for peace and freedom. Oswald’s memorialization of the so-called “smaller” deaths in the Iliad isn’t only a response to the contemporary context but also a way of excavating the universal and the relatable, as well as the historical parallel in the epic.

On a linguistic level too, Oswald is working to recontextualize Homer’s text in the twenty-first century and prove that oral poetry is “still alive and kicking” (x). In Oswald’s version, modern imagery finds its way into the ancient narrative. Whether it’s one of the brothers—Phegeus or Idaeus—facing impending death as “like a lift door closing / Inexplicable Hephaestus / Whisked one of them away / And the other died,” or Hector standing “in full armor in the doorway” of his home, impatient to return to battle “[l]ike a man rushing in leaving his motorbike running,” Oswald’s translation bridges antiquity with contemporary life (13; 69). For instance, the temperamental lift door, straight out of this century (or the last), pops up effortlessly in the text. In a blunt language that meets us like “a flying spear”—as it did one of the brothers—the scene juxtaposes the banal, everyday disappointment of lift doors closing before one can slip in with the tragic despair of death closing in on those at war (13). In her afterword to Memorial, Eavan Boland points out that “[u]ntil it was written down and standardized, it’s not unreasonable to imagine that the reciter of the Iliad might well have intervened in the poem, adding and embellishing” (89). And there is no reason for the new, contemporary reciters of the Iliad to refrain from intervening as well. As translator-creators, they have the opportunity to “retrieve the poem’s enargeia,” to find its imprint in today’s “bright unbearable reality” (ix). In Boland’s words, for the reader of this age who is “living in an era of fixed text, there is something bright and moving in this image of the Iliad as a river, not an inland sea, flowing in and out of song, performance, memory, elegy and human interaction” (89). The image of lift doors, then, opens a realm of possibilities, allowing the text to grow into its new context. Its appearance is not at all incompatible with the source if seen “as an extension of rich and ancient improvisations,” providing a hospitable soil “to new makers” (89-90). Indeed, when working in a language other than Greek, any new maker must necessarily be a poet-translator.

Oswald’s most striking moves as a poet-translator are her manipulations of the Homeric similes and short “biographies” of the deceased. In her translator’s note, she clarifies that her “‘biographies’ are paraphrases of the Greek, [her] similes are translations” (x). Focused on translating the text atmospherically rather than literally, Oswald shifts similes from context-dependent phrases to portals that reveal modes of life and being. Paraphrase, by contrast, while still rooted in context and characters, allows her to distill the life stories of the lamented and elevate unique details of their lives. No longer buried under the immensity of the Iliad’s deeds and doers, these individuals emerge as human beings rather than as expendable plot points.

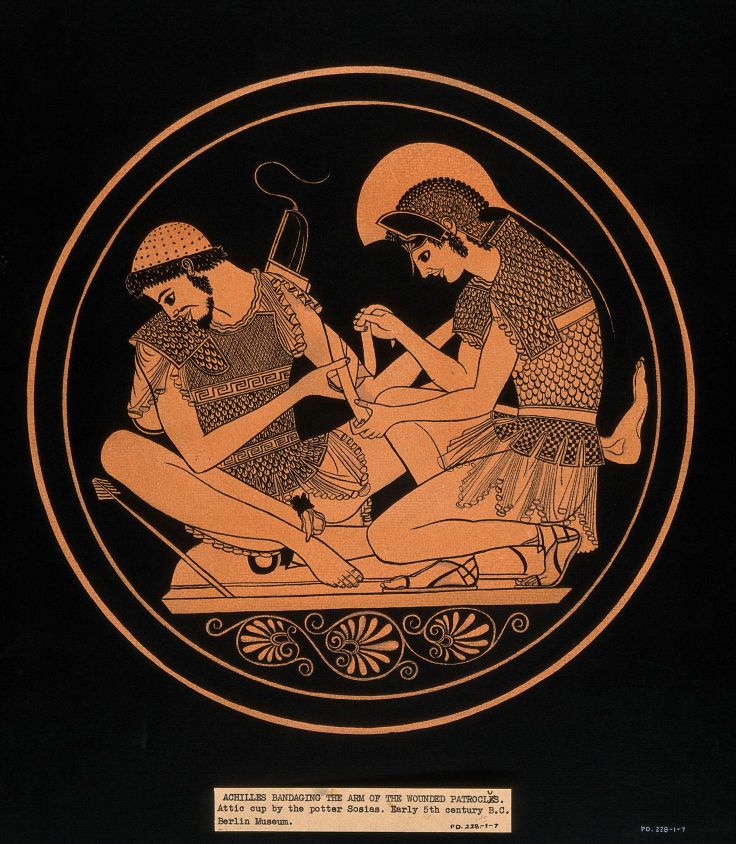

To excavate such details, Oswald employs paraphrase in ways that are both radical and, at times, counterintuitive. Georgina Paul highlights an instance where Oswald condenses a passage of over sixty lines recounting the fight between Menelaos and Euphorbas into “a mere two lines” (147). In Wilson’s translation of the Iliad, Euphorbas is the first to strike the mighty Patroclus, setting into motion the chain of events that will awaken Achilles’ wrath. When he dies, “His hair, pinched into locks adorned with spirals / of gold and silver, lovely as the Graces’, / was soaked with blood” (17.63-65). In Memorial, we’re only told that “EUPHORBAS died / Leaving his silver hairclip on the battlefield” (64, emphasis in the original). This (para)phrasing transforms the silver hairclip from mere adornment into a cherished possession and a defining marker of Euphorbas’ identity, however one might interpret its significance. Oswald’s couplet shifts our attention away from the hero’s deeds to a singular, evocative detail. Such a move dramatically undermines conventional notions of fidelity yet leaves the reader with a striking image of the individual behind the warrior.

Oswald’s interpretive process is rooted in memorializing the people within the text and embracing its possibilities, rather than transmitting an indisputable truth. To borrow Lawrence Venuti’s words, Oswald understands meaning to be “a plural and contingent relation, not an unchanging unified essence” (18). She sees an opening in the source text, an opportunity to amplify an almost-silent detail, and excavates what is buried beneath the traditionally translated meaning. Her method stands as proof for Venuti’s claim that “a translation cannot be judged according to mathematics-based concepts of semantic equivalence or one-to-one correspondence” (18). Through paraphrase, Oswald bypasses the demands of equivalence.

While paraphrasing exemplifies Oswald’s irreverence for the word as a unit of translation, she demonstrates a similar approach with Homeric similes as larger units. Paul emphasizes that similes in both Homer and in Oswald provide a “quality of lyric strangeness” by letting the audience “into a parallel world to the battlefield, whether of nature or of domestic daily ritual” (150). However, this effect “is heightened in Oswald’s poem through her treatment of Homer’s similes as free units. She lifts them out of their original context and re-attaches them in new ones” (150). Her approach not only casts the fate of the deceased men and their loved ones in new, strange light, but, more importantly, allows Oswald to translate the atmosphere of the Iliad, its enargeia, as vividly as possible.

Tracing Oswald’s translation of the Homeric similes back to the images that may have inspired her reveals a rich network of similar imagery in the original text. It also shows how the lyric impulse and recurring images weave through different parts of Homer’s work, creating subtle undercurrents that disrupt the epic narrative. One striking example is the image of a little girl clutching her mother’s clothes. Following this image means tuning into not just the recurring motif of helpless children reaching for their parents, but also the presence of fabric and the act of wrapping around bodies. While Homeric similes are often seen as isolated moments, Oswald’s translation unfolds the text like a piece of cloth, revealing its patterns when fully opened. These similes become more than rhetorical devices—they form imagistic threads that permeate the entire work. Here is the simile from Memorial:

Like when a mother is rushing

And a little girl clings to her clothes

Wants help wants arms

Won’t let her walk

Like staring up at that tower of adulthood

Wanting to be light again

Wanting this whole problem of living to be lifted

And carried on a hip (19)

This extended simile follows the death and biography of Scamandrius, weaving together unmistakable semantic and imagistic threads that run through both the Iliad and Oswald’s Memorial. In both texts, Scamandrius, a hunter who “knew every deer in the wood” and had been trained by none other than Artemis, becomes the hunted as he’s trying to flee from Menelaus (Oswald 19). While Artemis in the Iliad simply “could not help” Scamandrius, Oswald’s Artemis, with “all her arrows,” fails to “help him up” (Wilson 5.70; Oswald 19). This image of a protective, guardian-like Artemis struggling to lift Scamandrius reaches across the next stanza, where a daughter reaches out to her mother, “[w]ants help, wants arms” (19).

In Wilson’s translation, Menelaus “forced him down” in the final moments of the passage (5.76). The downward movement of the image—Scamandrius being hunted, struck down, his body lain on the ground—carries us deep into the grim cemetery of Homer’s Iliad (5.65-76). And yet Oswald takes a different approach. Rather than simply recording the death, she draws our attention to the lyric interruption of the simile that shifts the focus from the battlefield to the personal, private realm. The image of Scamandrius’ death becomes a pivot, leading us into the quiet, tender space of the child reaching for her mother, wanting to be lifted. In other words, Oswald’s approach to this moment is not just a creative reimagining of the scene; it’s a way of lifting the body off the ground of Homer’s narrative and allowing it more time, more space to exist. In her hands, the “small” deaths of Homer’s epic are not erased or dismissed; instead, they are stretched, reframed. They are given significance, a kind of mournful grace.

Interestingly, in the Iliad, Scamandrius’s lineage appears at the very beginning of the passage, following the Homeric tradition of presenting children as extensions of their fathers. Oswald, however, places this detail at the end of the stanza, transforming it from a mere patronymic construction into a full and unembellished statement: “His father was Strophius” (19). This then becomes the hinge of Oswald’s transition into the simile of the mother and daughter, and that shift is crucial. We go from “His father was Strophius” to “Like when a mother is rushing / And a little girl clings to her clothes” (19). More than a passing detail, this is a deliberate movement from the patriarchal world of the Iliad into a more intimate space, a world of yearning and tenderness. In Oswald’s version, the narrative of war, violence, and heroism gives way, if only momentarily, to a child’s private longing for her mother. Instead of leaving Scamandrius’s body on the battlefield as just another casualty, she lifts him out of the text, transposing his death into a more human, familial context. This shift, from battlefield to home, hunting to nurturing, speaks to the power of her translation. Oswald excavates the latent, sometimes hidden forces within Homer’s epic and allows them to resonate. Her work carves out space for the small and overlooked, drawing attention to them not as mere fragments of a larger narrative but as images that hold the possibility of other stories, other truths.

As we move from the harsh realities of the battlefield to the folds of a mother’s clothes, “like when a mother is rushing” draws us into the space of simile (19). Here, we encounter a child’s helplessness—her need for care, compassion, and guidance, alongside her fear of, and anticipation for, the burden called living. The stanza is in fact built on two parallel similes. First, “a little girl clings to her mother,” trying to keep her from moving, longing to be lifted up into her protective embrace. Then comes “that tower of adulthood,” an image that mirrors the vertical figure of the mother but now stands unapproachable and unyielding like a monument (19). The initial desire remains the same at its core: to be lifted up and away from the life’s burdens. However, as the mother’s nurturing presence gives way to something more distant and imposing, the language shifts as well. From a restless, apprehensive child-talk (“wants help wants arms”), we move to a more existential meditation that lifts the child’s plea to a symbolic level: “wanting this whole problem of living to be lifted” (19). The repetition of “want” within the third line now reappears as anaphora, with “wanting” echoing at the start of subsequent lines. Now tied to a more existential language, this repetition takes on a ritualistic quality, as if these lines are meant to be sung—“wanting to be light again”—like the language is reaching for a hymn to lift the spirit (19). And with that, Oswald’s desire to ritualize the moment of death fully emerges, allowing us to experience the simile as an act of ritual. Before returning to the battlefield and to “that whole [deadly] problem of living,” we witness one last impulse to lighten the burden, to see it personified as a child, something that could be “lifted and carried on a hip” (19). In the earlier lines of the stanza, the child exerts her will, refusing to “let her [mother] walk” (19). Here, however, the act of lifting remains only a longing, suspended in uncertainty, never fully realized. And yet, because it’s left unresolved, Oswald’s simile offers us a space to dwell in possibility.

But there is yet another layer to Oswald’s incredible construction of this simile. It’s worth considering the images that run through Homer’s Iliad, quietly underpinning the scene before us. While no single image in the Iliad directly corresponds to this one, Oswald instead weaves together multiple references from the text, each serving different functions, to recreate the epic’s atmosphere in lyric form. The tactile reference to clothes may be traced to the recurring image in Homer’s text of bodies wrapped in fabric or emotions. At different moments in the Iliad, Agamemnon dons his cloak, Aphrodite envelops her son Aeneas in the folds of her dress, “In saffron robes Dawn spread[s] across the world,” and “desperate grief wrap[s] round the heart of Hector” (2.54; 5.416-17; 8.1; 8.162-63).

And then there are the more explicit scenes that this simile immediately recalls: In Book 8, before Hector returns to the battlefield, we witness an intimate family scene between him, his wife Andromache, and their son: “noble Hector reached towards his son. / The baby wailed and wiggled back to snuggle / into his well-groomed nurse’s lap and dress” (8.635-637). The “terrifying horsehair plume” on his helmet stares down at the baby, frightening him—not because he understands war, but because it simply looks menacing—just as Oswald’s “tower of adulthood” looms over the little girl, an unsettling symbol of what lies ahead (8.639; Oswald 19). Once Hector removes his helmet, he takes “him in his arms to rock and cuddle,” before returning him to Andromache, who “let[s] him snuggle in her perfumed dress”—a child clinging to his mother (8.645, 656). Elsewhere in the same book, a simile evokes a similar scene, this time depicting Teucer shooting and killing his mark on the battlefield, then taking cover “behind the mighty shield of Telamonian Ajax…like a child / hiding himself beneath his mother’s skirt,” returning to the safety of his protector’s arms after braving the brutal reality of war (8.362-63). Finally, in Book 16, Achilles utters the simile most closely connected to Oswald’s. Unaware of the fate awaiting Patroclus, he mocks his dear friend, who is weeping for his comrades: “Why have you started crying now, Patroclus, / just like a silly little girl, who runs / beside her mother begging, ‘Pick me up!,’ / and tugs her dress and gets under her feet?” (16.8-11). Of course, as we know, Patroclus will soon be crushed to death under that “whole problem of living” (Oswald 19). He will slip into Achilles’ armor just like a child dressing in her mother’s clothes, but it will not offer him the “help” and the “arms” he needs (Homer 16.86; Oswald 19). It, however, offers us readers the final bead in a string of disparate, approximate references that Oswald pulls from the text to translate the epic’s enargeia into lyric.

Essentially, Oswald recontextualizes parts of the text to access its enargeia. Simile, by nature, lends itself well to this purpose. Unlike metaphor, which equates two points of comparison, simile—with its conspicuous “like,” “as,” or “as if” perched in between the tenor and the vehicle—merely approximates. Rather than fixing a single, objective equivalence between its two parts, simile opens up possibilities of similarity, calling attention to the act of comparison itself. By embracing these possibilities and moving beyond the nominal sense of the text, Oswald uncovers connections between seemingly disconnected parts of the Iliad, linking Andromache’s tenderness, Hector’s grief, and Achilles’ mockery. She thus gives the text the space to breathe within a broader context. In this way, her similes pave the way to Carson’s “third place” between naming and chaos where ambiguities and possibilities live (26). Rather than producing an indisputable equivalent, Oswald’s similes harness the power of diverse events that capture the breadth of human experience. This follows Charles Altieri’s view that simile does more than rename; it draws us into a web of analogies and different perspectives:

Perhaps it can matter that in the place of providing new names simile calls our attention to what the act of naming itself can involve. Simile invites us to turn away from cognitions to something like participation in complex attitudes that develop analogies and correspondences. (137)

If we take simile, as described by Altieri, as a model for translation, Oswald’s intentions in composing Memorial become clearer: by stripping the epic of its narrative, Oswald dispels the veil of story that cloaks the real cost of war, and, in doing so, draws attention to the fact of dying in war itself. Through her liberal manipulation of the original, Oswald casts a new web of relations, allowing the reader to approach, and empathize, even as they realize the unbridgeable gap between the different experiences. To communicate—translate and transmit—her reading of the Iliad, Oswald takes advantage of the gap between the target and source texts, inserting what she discerns as the essential meaning in between. Ultimately, this is the task of the creative translator: not to erase the gap between source and target, but to make it visible—an opening through which we can glimpse different possibilities.

Works Cited

Altieri, Charles. Wallace Stevens and the Demands of Modernity: Toward a Phenomenology of Value. Cornell University Press, 2013.

Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Illuminations. Edited by Hannah Arendt. Translated by Harry Zohn. Schocken Books, New York, 1968, pp. 253-264.

— “The Translator’s Task,” Translated by Steven Rendall. TTR, Volume 10 (2), 151-165.

Carson, Anne. Nay Rather. Sylph Editions, 2014.

Cox, Fiona and Elena Theodorakopoulos, editors. Homer’s Daughters: Women’s Responses to Homer in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Oxford, 2019.

Godard, Barbara. “Theorizing Feminist Discourse/Translation,” Translation, Semiotics, and Feminism. Routledge, 2021.

Hahnemann, Carolin. “Feminist at Second Glance? Alice Oswald’s Memorial as a Response to Homer’s Iliad.” Cox and Theodorakopoulos, pp. 89-104.

Homer. The Iliad, Translated by Emily Wilson. W. W. Norton, 2023.

Mathews, Harry. The Case of the Persevering Maltese: Collected Essays. Dalkey Archive Press, 2003.

Oswald, Alice. Memorial: A Version of Homer’s Iliad. W. W. Norton & Company, 2011.

Paul, Georgina. “Excavations in Homer.” Cox and Theodorakopoulos. Oxford, 2019, pp. 143-160.

Wilson, Emily. “Translating Homer as a Woman.” Cox and Theodorakopoulos, pp. 279-297.

Venuti, Lawrence. The Translator’s Invisibility: A history of translation, Routledge, 1995.

Zeynep Özer, a native of Ankara, Turkey, earned her MA in English and taught at the University of Connecticut before moving to Chicago. She has a particular interest in hybrid forms, lyric essays, and translation as a form of creative writing. Her translations of Gülten Akın’s and Enver Ali Akova’s poetry have appeared in World Poetry Review and Asymptote.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, April 8, 2025