“Blooming to Surface”: Edith Adams on her Debut Book-length Translation of Daniela Catrileo’s Guerrilla Blooms

Edith Adams interviewed by Michelle Mirabella

How might poetry become its own kind of territory, a place not where historical wounds are necessarily resolved or healed, but where other possible futures or narratives can be imagined?

A trilingual book of poetry featuring Spanish, Mapudungun, and English, Daniela Catrileo’s Guerrilla Blooms (Eulalia Books, December 2024) was recently longlisted for the 2025 National Translation Award in Poetry. The work’s translator, Edith Adams, is flourishing, and it is fitting in more ways than one for her to have made her debut with Guerrilla Blooms. I was lucky enough to attend the launch event for this work in person last year at City of Asylum in Pittsburgh, and in the weeks surrounding the new year, Edith and I had the opportunity to talk further over email about the book. What follows is a conversation between two friends, coming up in this field together, about Edith’s translation work of Daniela Catrileo.

Michelle Mirabella: We’re just about one year out from the publication of Daniela Catrileo’s Guerrilla Blooms in your translation, your book-length translation debut. Before we get into Daniela’s work and the book itself, who is Edith Adams the translator? What guides your selection of and approach to a text?

Edith Adams: Something I think about a lot as a translator and educator is the importance of highlighting the linguistic and cultural diversity of the Spanish-speaking world, which itself is comprised of more than 500 Indigenous languages! When I teach my beginning Spanish students, they’re often surprised to learn that many of the words we’re encountering come from Indigenous languages, let alone that “Spanish” is made up of different accents, phrases, and grammars, a variety that has been largely influenced by histories of colonization and patterns of migration. As a translator, I’m excited by texts and translation approaches that celebrate the rich linguistic fabric of Latin America and call attention to the peoples, histories, and cosmologies that are often overlooked, particularly in representations of “Spanish” here in the United States.

MM: You talk about coming to Daniela Catrileo’s work in your translator’s note, can you share more with us here about how Guerrilla Blooms resonated with you as a reader and translator, particularly in regards to your priorities as a translator and educator?

EA: I first came to Daniela’s work in early 2020 by a stroke of pure luck. At the time, I was enrolled in a multilingual translation workshop as part of my doctoral coursework at USC and, for our final project in the class, we were tasked with translating a selection of multilingual poems. A friend of mine had just given me a copy of Daniela Catrileo’s Guerra florida / Rayülechi Malon, which was the first of Daniela’s books to be published bilingually in Spanish and Mapudungun. The text seemed like a perfect fit for the assignment, so I decided to translate it for my final project.

When I read the collection, I had a kind of coup de foudre moment; in Daniela’s poems, I saw someone who was trying to grapple with many of the same questions that had led me to pursue a Ph.D. How does language shape who we are and how we understand ourselves? If language, as it is for the Mapuche, is intimately connected to territory, what happens to language – and to identity – when that territory has been stolen or can no longer be accessed? And how might poetry become its own kind of territory, a place not where historical wounds are necessarily resolved or healed, but where other possible futures or narratives can be imagined? Daniela’s work helps me think not only about the consequences of linguistic and territorial loss, but also about how literature can serve as a vital political tool for contesting entrenched narratives and creating language anew.

Reading Daniela’s work and learning more about contemporary Mapuche poetics through that process also helped me better understand how trends in publishing and processes of canon formation amplify certain voices and silence others. Here I was pursuing a doctorate in Latin American literatures and cultures, and yet I knew very little about the history of the Mapuche, let alone the dynamism and vitality of their culture in the present. Translating Daniela’s work felt important to me not only because I think she’s creating some of the most urgent and innovative work to come out of Abiayala today, but also because it’s important to me that English-language readers encounter a fuller and more diverse picture of what “Latin America” is – and can be.

MM: I want to acknowledge Guerrilla Blooms as a book object. The English-language edition is formatted to feature your translation followed by the Spanish-language source text with its Mapudungun translation, line by line, below it in gray scale – a visual echo. As you shared, the source text is a bilingual edition of the work, and now its English-language translation adds to that instead of, perhaps, writing over it. How did you and your publisher come to this format?

EA: When I was looking for a publisher for Guerrilla Blooms, it felt important to me that the text be published in a trilingual edition, particularly because Guerrilla Blooms is the only of Daniela’s texts to be published bilingually. In a text about colonization and its continuation into the present, I see the placement of Daniela’s Spanish alongside Mapudungun as a forceful insistence that Mapudungun – and the Mapuche – endure, despite persistent attempts by the Spanish and, later, by the Argentine and Chilean states, to erase them.

I have to give a huge shout out to Michelle Gil-Montero, Jeannine Pitas, Mallory Truckenmiller Saylor, and Tyler Friend, who make up the extraordinary team at Eulalia Books. From the very beginning, I felt like they understood my vision not just for the translation, but for the book’s presentation, and we thought a lot about how to format the collection in a way that could preserve its multilingual nature. This was a particularly difficult task, given that Guerrilla Blooms is comprised of poems that form an overarching narrative. While a book of discrete poems might have been published with the English, Spanish, and Mapudungun presented back-to-back, we worried that this approach would interrupt the rhythm and propulsive musicality that’s so important to the collection.

In the end, Michelle came up with the idea of placing the Mapudungun below the Spanish in a lighter gray font, which was inspired by her work translating Andrés Ajens and his thinking on the aguayo, or the Andean carrying cloth. We liked how the grayscale could be read in multiple ways. On the one hand, for English-language readers who might not be familiar with Mapudungun, we wanted the grayscale to gesture toward Mapudungun as an endangered language, one that remains threatened by ongoing efforts to suppress its use and assert Spanish as the national tongue. At the same time, we wanted the Mapudungun to form a kind of shadow text, haunting the Spanish and threatening its dominance. Much like the story that Guerrilla Blooms tells, we hoped that Mapudungun on the page might complicate and unsettle the Spanish, calling into question its authority and singularity.

MM: This work and its language is deeply connected to the land with a vibrant floral motif that really comes to the fore in your translation. I see the translator at play in certain moments of felicitous opportunity such as with “wilts and withers” for the epigraph’s “se agota en absoluto” or “ships blooming to surface” for “naves anunciando aflorar” in Riot of Celestial Bodies. The poetic license of the translation honors the artistry of its source. So, blooms – how did you navigate translation decisions related to the floral motif?

EA: The original title of the text in Spanish is Guerra florida, which refers to pre-Columbian flower wars, a common ritual war carried out between members of the Aztec Triple Alliance. While readers can interpret this reference in multiple ways, I see it as a gesture that immediately unsettles a concrete sense of place or time. Are we in pre-Columbian Mexico? Chile in the present? An imagined space of myth? The collection, quite purposefully, never allows readers to locate themselves in a single space or time, and the original title sets us off-balance from the get-go by gesturing toward its pan-Indigenous investments.

When I was thinking about a title for the collection in English, however, I worried that a more literal translation, Flower Wars, might be lost on U.S. readers, who would likely be unfamiliar with Aztec Flower Wars and their significance. I ultimately arrived at Guerrilla Blooms because it suggested an ongoing conflict against a larger opposing force, while also capturing the botanical references throughout the poems. As you note, the poems repeatedly draw upon language related to flowers, blossoms, or blooms, and I realized that the use of those words shifts as the collection progresses. In the early poems before the arrival of the invader, words related to flowers are more directly linked to the thing itself: to blossoms, flowers, or trees bearing fruit. When the colonizers begin their assault, however, the floral motif takes on a new shape, such as in the example you cited: “naves anunciando aflorar.” While the verb “aflorar” derives from the process of a plant breaking through soil to reveal itself, it more commonly means to surface, appear, or emerge in contemporary Spanish. Uses like this recur during the battle, where words previously connected to the land’s natural cycle instead become linked to violence and the machinery of war. In these moments, I wanted the English translation to underscore this etymological link, particularly since this is a collection that’s thinking deeply about how colonization endures through language.

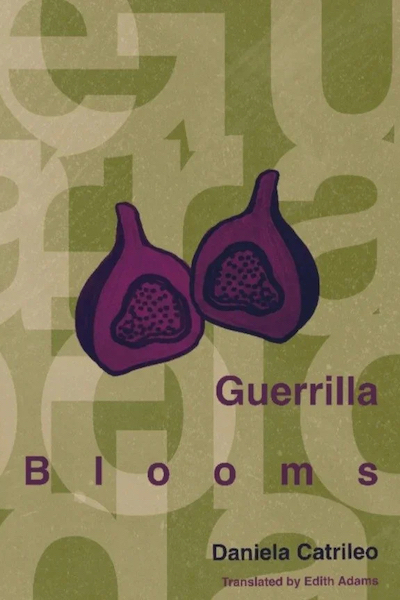

The book’s cover in English, which was designed by Tyler Friend at Eulalia and developed through discussions with Michelle Gil-Montero, also gestures toward the poems’ botanical language. For those who haven’t seen it yet, the cover depicts the various titles of the book (Guerrilla Blooms, Guerra florida and Rayülechi Malon) superimposed over one another, with a fig at its center. Did you know that a fig isn’t a typical fruit, but rather a cluster of hundreds of tiny flowers that bloom within the receptacle that we think of as a fig? We loved this image not only for its insurgency – flowers disguised as fruit – but also for how it emphasized the collective nature of the struggles that bloom throughout the text. While the poems center on an unnamed protagonist who transforms through her fight to protect her territory, I see the collection like a fig: a struggle that is, in fact, always multiple, always interconnected.

MM: You’ve preempted my question about the cover; I was very curious about the fig! How beautiful. Now, I know you’re working on Daniela’s Rio herido – translating multiple works by one author can be such a gift. In thinking about the overarching themes of Daniela’s oeuvre, what translation opportunities are you seeing in this new project that connect back to Guerrilla Blooms?

EA: I agree with you completely about the joys of translating multiple works by the same author! For me, one of the greatest gifts of translation is the opportunity to spend enormous amounts of time inhabiting someone else’s words and ideas. Particularly in the case of Daniela, who is someone I also write about in my academic work, translating her poetry is an opportunity to think alongside her about the “burning questions” that animate her work, and which she often circles from different angles, genres, and styles. In the case of both Río herido and Guerrilla Blooms, I see Daniela thinking deeply about the effects of colonization, not just upon a territory but also its language. In different ways, poetry serves in these collections as a space where the effects of colonization – upon history, identity, language, culture – can slowly be dismantled or reimagined. What separates these two works, however, is their form. While in Guerrilla Blooms there’s a proliferation of signs and images, in Río herido we find only silence, ruptures, and white space. This experimentation with genre, media, and form is typical of Daniela’s work – in addition to being a poet, she writes prose and essays, teaches philosophy, and creates sound, video, and performance art. As a translator, while each of these projects is seeking out interconnected “burning questions,” I want to make sure that I’m careful to attend to their formal differences.

I have been working on a translation of Río herido for about five years now, and its form has made it both a challenging and fun collection to work on. In particular, Río herido has me thinking a lot about how to translate silence or absence. One example of this challenge is the poem “Aprendimos a leer a golpes,” [“We learned to read by blows”] which is three lines long and describes the violence of the Chilean educational system, where Mapuche students would be punished for speaking Mapudungun rather than Spanish. The poem’s conceit hinges upon the letter “h” in Spanish, which is always silent when it begins a word. In addition to starting and ending with words that begin with a silent “h,” which forms a kind of “bookend of silence” around the text, the poem also connects the silent “h” to the word “herida,” or “wound,” which is a central image in the collection. While English offers several silent letters for a translator to play with, finding a translation that can capture all the elements I want it to have has been a real – and potentially impossible – challenge! I’ve had to learn to trust my instincts as a reader of poetry and a translator, rather than continually revise or second-guess my choices in search of that “perfect” word that can do it all.

MM: As translators our work is, in part, mitigation of potential loss, but there’s this fear of what’s “lost in translation” that can cloud the view of a translation as a work of art in and of itself. In your time with these two works, navigating these challenges you just described, I want to move away from loss and hear what you think the translations have gained – in what way are they their own originals?

EA: I was thinking about this exact tension between loss and gain as I was answering your last question! When I teach translation to my college students, I like to start my classes by asking students to define translation. What does a translator do? What is the relationship between a translation and the original? Without fail, they always articulate translation in the terms you just stated – as a necessary loss that, regardless of the skill of the translator, will always be inferior to the original text. I work hard with my students to think not just about what we lose in translation, but also, as you said, what we gain; those felicitous moments when the target language offers something new to the text, teasing out something latent or amplifying an image or sound in unexpected ways.

To give an example of one of those felicitous moments, in one of the poems in Guerrilla Blooms, Daniela writes in Spanish, “Colchonetas y orina / siguen su curso y en vez de arroyos / un océano de cucarachas se retuerce / en cañerías de cobre.” This was always such a visceral image to me, and the alliterative quality of the Spanish creates a tight, propulsive rhythm that mimics the squirming of cockroaches in narrow pipes. When I was translating these lines into English, I found that the words and sounds we have available allowed me to play not just with alliteration, but also with twisting, shifting rhymes. The end result – “Mats and urine / follow their course and instead of streams / an ocean of roaches writhes / in copper pipes” – felt so exciting because the unique gifts of the sounds of English helped to turn the volume up on that squirming, visceral claustrophobia that I hear in the Spanish.

Beyond micro examples like these, however, I think of a translation as the whole book, and I’m proud of what this project offers to readers in English, and what I hope Río herido will continue to offer when it, too, hopefully comes out. For Guerrilla Blooms, we added several paratextual elements to the text to enrich the collection for English-language readers. In addition to my translator’s note, Daniela wrote the introductory essay “Honor the Unspeakable Fiction” just for this edition in English. The essay provides important context about not only the creation of the collection, but also reflects deeply on the power of poetry to reimagine entrenched histories and narratives. Very few Mapuche poets have been published in English, let alone with Mapudungun visible on the page alongside the Spanish. I feel proud that Guerrilla Blooms helps, even if only in a modest way, to expose more readers to the incredibly vibrant, urgent, and inventive work of contemporary Mapuche poets, activists, and creators who are widely underrepresented in English translation.

MM: The act and art of translation is full of decisions, one of the first among them being what you choose to translate. As your translation career continues to unfold, what can we readers expect to see from Edith Adams?

EA: I’ve been reflecting lately on just how significantly Daniela’s work has shaped my life and career trajectory in ways that I never could have imagined. While translating Guerrilla Blooms, I began reading a wide variety of Mapuche poets and worked closely with Daniela to learn more about Mapudungun and the cosmology of the Mapuche. Through this process, I developed not just a deep appreciation for Mapuche poetics but also realized how much my understanding of the Americas has been shaped by dominant narratives. To give you an example, I grew up in Phoenix, Arizona near a street called “Indian School,” where there was a U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school from 1891 until 1990. In school, we regularly had units about local Arizona history, but it wasn’t until I went to college and took a course on Indigenous histories that I learned what had happened at the boarding school in my own backyard. When I lived and studied in Argentina, I had a similar experience. In our classes, we learned all about the desaparecidos, but never about the Conquest of the Desert, when the Argentine state killed thousands of Mapuche and forced thousands more into captivity and concentration camps.

This is a long way of saying that the books and poems that I love as a translator are those that ask me – and hopefully other readers – to see the world differently and thus help me to understand it more fully. In the coming year, I hope to submit Río herido for publication, while also continuing to collaborate with other Mapuche poets and activists. I’d especially love to translate a collection by Viviana Ayilef, a poet from Puelmapu, whose poems are just extraordinary, as well as the work of Mapuche weichafe, Moira Millán, whose most recent book Terricidio is an incredible contribution to thought and Indigenous resistance movements. My ultimate pie-in-the-sky dream is to collaborate with Mapuche poets, artists, and activists to create an anthology that would interweave Mapuche poetry, art, critical thought, and resistance efforts, helping to highlight the rich diversity of Mapuche culture and those who are working to keep it alive.

Edith Adams is a translator of contemporary Latin American writing, with a focus on Mapuche poetry. Her translation of Daniela Catrileo’s Guerrilla Blooms was longlisted for this year’s National Translation Award in poetry and was published by Eulalia Books in 2024. Her translations have appeared in anthologies, such as Best Literary Translations 2024 (Deep Vellum)and La Lucha: Latin American Feminism Today (Charco Press), as well as various literary journals. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures at Bowdoin College.

Michelle Mirabella is a Spanish-to-English literary translator and editor. The translator of Catalina Infante’s debut novel, The Cracks We Bear (World Editions, 2025), her work also appears in Best Literary Translations (Deep Vellum, 2024), Daughters of Latin America (HarperCollins, 2023), and in venues such as World Literature Today, Latin American Literature Today, and Southwest Review. A former ALTA Travel Fellow, Michelle holds an M.A. in Translation and Interpretation from the Middlebury Institute and is an alumna of the Banff International Literary Translation Centre and the Bread Loaf Translators’ Conference. She currently teaches in the Applied Spanish Language and Culture Graduate Certificate program at the University of Indianapolis. Find more of her work at www.michellemirabella.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, January 27, 2026