Translating and Other Extreme Sports

A conversation between Miklós Vámos, Ági Bori, and Jenn Director Knudsen

Translation is like weaving a giant carpet by hand.

When acclaimed Hungarian author Miklós Vámos and aspiring literary translator Ági Bori first met back in 2012, few could have predicted that a decade later they’d be an in sync author-translator pair, ushering a broad range of translations toward publication. By now, with a number of pieces published, including excerpts, interviews, and short stories, books are also underway. It was evident from the first moment of their meeting that they had a common goal. The duo sat down for an interview with editor and journalist Jenn Director Knudsen, on whose editing skills they have relied, shall we say, more than once. For further reading, a heartfelt personal essay in Apofenie gives readers a broad overview of Miklós’s career and the current political situation in Hungary. A humorous excerpt from a book about his mother in the Los Angeles Review is sure to entertain, and is best followed up by a rib-tickling piece in Hungarian Literature Online.

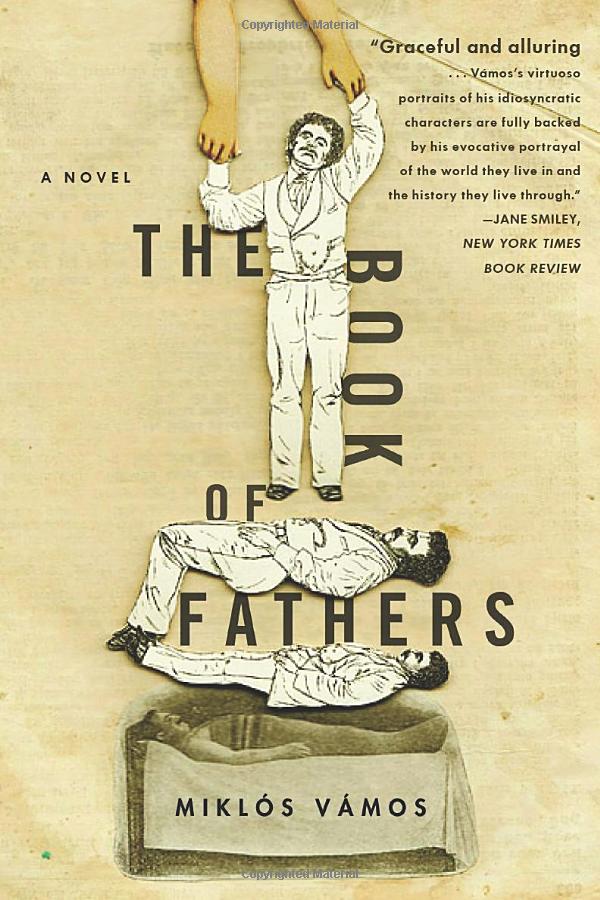

Jenn Director Knudsen: I still remember the day about 10 years ago when you gave me The Book of Fathers as a birthday gift. You’d said I’d love it. I did, and that was my introduction to Miklós Vámos, more of whose books I wanted to read. However, as is too often the case, his other books were not translated into English and thus his genius remained elusive. You knew I wouldn’t be the only one feeling this way about Miklós Vámos’s works.

Soon thereafter, you metamorphosed from a voracious reader into a translator; I’ve had the privilege to edit some of your clever work and its growth. Let’s look back at this very personal journey of yours with one of Hungary’s most renowned authors.

Ági Bori: The wonderful anecdotes of established translators have always fascinated me. As an emerging translator, however, occasionally I find myself enshrouded in a cloud of doubt as to the everyday challenges that come with the territory, which are familiar to many highly regarded foreign authors when trailing through the labyrinthine scene of translated manuscript into published book. About six years ago during a winter afternoon it hit me: I had an insuppressible urge to give translating a serious try. I had dabbled in translation before, but now it had become the driving force behind my every waking thought. My initial inspiration came from a book whose complexity truly mesmerized me. It was Miklós’s 2016 novel, Swan Song. Back then I knew nothing about the small amount of translated books on the U.S. market, nor did I know what a Herculean—but immensely satisfying—task literary translation was. But let’s go back a bit further in time, to the turn of the millennium. The book that made me fall in love with his work and writing style (particularly his unending gallows humor) was The New York–Budapest Metro. Upon reading it, I knew I wanted more. I went on to read everything he ever published. It was when I wanted to share this experience with my literary friends that I discovered that only one, The Book of Fathers, had been translated into English. Something awakened in me, and I felt that, no matter how, I wanted to help increase that number and be part of the change. When he and I met in person more than a decade ago, he had no clear answer as to why his oeuvre hadn’t been published more widely abroad—the mystery surrounding the shortage of his translated works was something of a closed book. It likely was at that moment that the seed was planted: I wanted to bring Miklós Vámos’s works to a much larger swath of the reading world.

JDK: I am curious how your views and hopes of your works in translation compare to Ági’s unwavering enthusiasm?

Miklós Vámos: I have always thought that my job was to produce the masterpieces and other people should place and sell them. Believe it or not, in my youth there were no literary agencies or even lawyers in the cultural field. Our agent was a miraculous abstract person called Dumb Luck, and therefore the idea of having a literary agent didn’t occur to me for the longest time. But it seems like today, especially abroad, one cannot get by without one. When I landed a Fulbright fellowship and moved temporarily to the Yale University campus in the late 1980s, I was regarded as a playwright, since some of my plays were produced in Washington D.C. and at various theaters at Yale. At that time, a very famous agent, the late Robby Lantz, began representing me. Hélas, he wasn’t interested in books, only in plays and film scripts, as well as actors and directors.

In the early 1990s, when socialism collapsed, I returned home. I wrote new books, including some novels that were translated into multiple languages. As time went on, more were translated, but only sporadically. The real breakthrough was The Book of Fathers, in 2000. It was a raging success in Hungary, with 150,000 copies sold in the first year and more than 400,000 as of today in a country of 10 million. Thanks to agent Dumb Luck, a German publisher brought it out, and it became a bestseller in Germany, too. After that, the literary agent Susanna Lea called; her husband had read my novel in German and he was incredibly enthusiastic. Frantic, she said. So she offered to represent me all over the world. She tried to bring about an international film based on the novel—unfortunately, co-agent Dumb Luck didn’t help with this project. Never mind, I was happy. Time flew, and in the meantime I wrote five or six other novels. I was on top of the world. After this, I was certain that my other novels also would be published in the U.S. Instead, the Great Recession and its global repercussions reared their ugly head. No more of my books made their way onto the shelves of books translated into English. But I am an optimist at heart, hence my enthusiasm in general about life and books—both Hungarian and translated ones—remains boundless.

JDK: How has it been to translate for such a well-known author of your homeland and what experiences, both professional and personal, have you gained over the course of the last six years?

ÁB: It’s been such a privilege to get to know Miklós as a person and not solely as an author. I love his writing style and persona, and that is why I have become a fierce advocate for bringing more of his translated books to English-speaking readers. I am a small piece of the overall publishing puzzle, of course, but I do feel the great responsibility I have taken on to bring his words into another language. After what seems like an unjust dry spell, we have amassed a diverse collection of samples to present to publishers. In fact, just recently we’ve had more than a handful of articles and excerpts published in various respected literary journals. This, too, gives me great hope that we have breathed new life into some of his older books and are getting close to publishing an entire book, or more. Even though I am still an emerging translator, I have gained a lot of experience and confidence since I started. I have to say that Miklós has been my pillar throughout this journey. While he likes to say that his English is not that great, I beg to differ. It is much better than he claims it to be, and it’s definitely good enough for him to read my translations and get a good feel for them and then give me feedback. I’ve been lucky to have read many pieces that he’d written years ago in English, among them, for example, articles in The New York Times, and they helped me get a feel for his taste in English. I cherish our long-distance collegial relationship; it helps maintain my enthusiasm. It’s been wonderful for both of us to be able to exchange ideas via our proverbial Transcontinental subway.

JDK: You’ve worked with many translators before, and hopefully will work with many more in the future. What has your experience been like working with translators?

MV: First and foremost, I’m really touched that Ági, who left Hungary 30 years ago, still feels such a strong connection to her Hungarian culture, especially literature, and furthermore, to my books. I am always moved when translators are willing to spend many months, or even longer, on my books. That said, yes, I’ve worked with translators before, but with others we communicated less frequently. Mostly, they asked about the meaning of the old and out-dated words I had used in the first chapters of the Book of Fathers; those are admittedly hard to find in dictionaries. Thus, I compiled for them what I called a Hungarian–Hungarian dictionary. Old-world words and their actual modern-day meaning. They were very grateful. Everything else at that time was arranged by my agent. I am not sure an author has to or can collaborate with his translators, especially when he doesn’t even know them. But I am open to helping translators, if need be; that’s the least any author could do, given that the translators are the heavyweight champions who seamlessly transform words from one language into another, which is a feat in and of itself. I am able to understand English and French texts, German and Spanish ones somewhat, but for anything beyond those languages, such as my Chinese, Israeli, Danish, Dutch, and other translations, I am at the mercy of my translators.

JDK: You’ve built quite a network of connections since you started translating. What have been some of the highlights throughout it all?

ÁB: I have learned that translation is a labor of love. Working through them taught me so much about Miklós, his work, about my own thoughts and how my own brain works. I never realized that translation really could be defined as the closest form of reading. It is like weaving a giant carpet by hand. In addition, getting to know some of the people in the publishing industry has been the icing on the cake. Through submitting some of the translations, I have met amazing people. ALTA (American Literary Translators Association) is a great example. Its programs are so well organized and ALTA connects people from all corners of the world, whether they are emerging or established translators. I also was recently welcomed into a community of Hungarian translators when I was in Budapest in March. It was kind of like looking into a mirror—they are just as passionate about the Hungarian language as I am. It is my dream to continue this work and prove to myself that it is possible to go from hanging out on the periphery of the literary scene to being part of the community of translators who are chipping away at the mountain of untranslated Hungarian books waiting their turn.

JDK: I have really enjoyed getting to know your body of work over the years through editing it, and it is my hope that all this hard work, trust and collaboration will bear English-language fruit out of Miklós Vámos’s unique prose, ideas, images and story. I should not be the only non-Hungarian-speaking English-language reader with such privilege.

Miklós Vámos is a Hungarian writer who has published over 40 books, many of them in multiple languages. His most successful book is The Book of Fathers, which has been translated into nearly 30 languages. His ancestors on his father’s side were Jews who perished in the Holocaust. Fortunately, his father—a member of a penitentiary march battalion—survived. Out of the 5,000 Hungarian Jews sent off to their deaths late in World War II, only seven came back. His father was one of them. Vámos was raised in Socialist Hungary unaware he was a Jew. In an effort to save himself from his chaotic heritage, he turned to writing novels.

Originally from Hungary, Ági Bori has lived in the United States for more than 30 years. A decade ago, she decided to try her hand at translating and discovered she loved it. She is a fierce advocate for bringing more translated books to American readers. Her translations are available or forthcoming in Apofenie, Hungarian Literature Online, the Forward, the Los Angeles Review, MAYDAY, and NW Review.

Jenn Director Knudsen earned a master’s in journalism from UC Berkeley and is communications manager at Jewish Family & Child Services in Portland, Oregon. Given the choice, she’d rather be watching foreign films.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, June 6, 2023