“mit diesem grenzhandel / an der sprache”: A review of Uljana Wolf’s kochanie, today i bought bread

by Daniel Rabuzzi

Wolf is a trickster, the Hermes who shifts the boundary stones, inventing words in multiple languages.

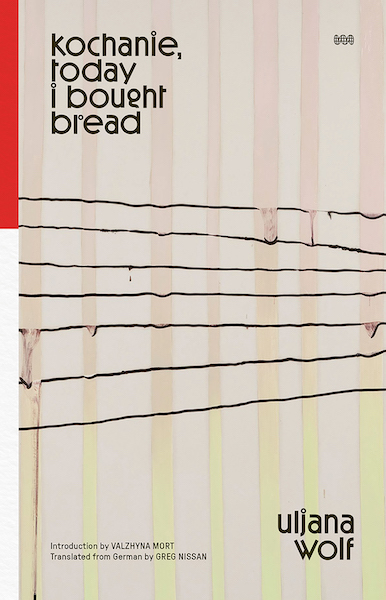

A review of kochanie, today i bought bread by Uljana Wolf, translated from the German by Greg Nissan, with an introduction by Valzhyna Mort. World Poetry Books, October 2023, 123 pages, $20.00. ISBN 978-1-954218-15-4

In the fall of 1993, I joined a busload of Germans from Stralsund on a “friendship visit” just across the border to Szczecin, one of many such outreach efforts after the fall of the Wall and German reunification. A man told me the last time he had seen Stettin – as it was named then – he had been a soldier retreating in the spring of 1945. A woman wondered if her childhood home still stood. Everyone anxiously anticipated what they would find in their fellow Pomeranian and Hanseatic city. Our Polish hosts were equally nervous. Despite professions of official unity and class solidarity made during the Communist era, few urban Poles had regularly visited East Germany and fewer German city-dwellers had routinely crossed the Oder in the opposite direction. For starters: what language would they use? The only one they shared – Russian – was anathema to both. The Poles knew more German than the other way around, so German it was, but speckled with Polish words that had Russian cognates, along with fugitive bits of English and French. Language was displaced and remade to match the displacement and refashioning of the border. Language struggled to reconcile itself, layered over silences, quivering like a bog of grievances both fresh and ancient, tight like a rope around the neck. Fortunately, the tongues of both groups understood the beer, bread, and sausages offered at the welcoming meal. The lone outsider, I sensed more than I understood what the Germans and the Poles were trying to communicate to one another, their strategies for cobbling together as well as withholding, eliding, or misdirecting meaning. I lacked a framework, not for the definitions of the words, but for the scaffolding beneath them. By analogy, I needed the archaeologist’s tools to discern the pilings – deep but often warped or buckled by centuries of tidal pressure – driven into the Baltic sand upon which the wharves and warehouses stand.

Uljana Wolf is the archaeologist I wish I’d had with me back then. Wolf was born in East Berlin in 1979, experienced the sudden disappearance of the German-German border, and splits her time between Berlin and New York City (she has taught at NYU and at Pratt). Her paternal grandmother comes from Maltsch/Malczyce, a village in Silesia, Poland, which was German territory before 1945. Wolf lived in the Silesian village of Kreisau/Krzyzowa in the winter of 2004. Her 2005 debut poetry collection kochanie ich habe brot gekauft won the Peter-Huchel-Preis, and appears in English for the first time via Greg Nissan‘s translation for World Poetry Books. Wolf’s originals and Nissan’s translations brilliantly reflect the fluidity of borders, the sensations of colportage and semaphore, the unavoidable displacement and inherent hybridity of language – and they indicate what words cannot capture, where indistinct murmurs or silence may be the only viable ways to converse. In “wie das murmelchen ins gedicht kam” / “how the little murmur came into poetry” (referring to a poem by the Polish writer Roman Honet), a sister stands on a garden path, clutching a jump rope, holding her breath:

ich heiße murmelchen my name is little murmur

ich bin aufgewachsen i grew up

mit diesem grenzhandel with this border trade

an der sprache on my tongue

In a piece that could stand for the entire book, “übersetzen” / “translate”:

mein freund: das ist my friend: this is

unsere schlaglochliebe our pothole love

unser kleiner grenzverkehr our little border traffic

holprig unter zungen clumsy under tongues

Clumsy murmurs are, however, exactly the opposite of how these poems sound and what they do. Wolf is a trickster, the Hermes who shifts the boundary stones, inventing words in multiple languages, embedding English into the German, sprinkling in Polish (“kochanie” means “my darling,” “my sweet”). As Valzhyna Mort notes in her evocative introduction: “The Polish word inside a German mouth is a site of mutual history, mutual silence.” Delving into fairy tale themes (reading Wolf’s poems is like stumbling into Bluebeard’s castle, or being surprised by Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged hut), Wolf darts and feints with gleeful wordplay and sonic blossom. Say her untranslated words aloud, feel the alliterative magic of skalds and scops, skeined and knotted to the core elements of language itself:

von klang an den hügeln hierarchisches knurren

und bellen in wellen: heraklisch erst dann hünen

haft im abklang fast nur ein hühnchen das weiß:

Wolf is herself an accomplished translator, having brought work by John Ashbery, Charles Olson, Matthea Harvey, Erín Moure, and Cole Swensen into German, and collaborated with Christian Hawkey on an erasure of Elizabeth Barrett-Browning’s sonnets. (I highly recommend Wolf’s readings of her own work: Lyriklesung: Uljana Wolf – im Gespräch mit Felix Schiller, and in conversation at the Goethe-Institut New York). The poems in kochanie are spare, each typically around 20 to 40 words in 6 to 14 lines, intricately constructed with words as compressed as coils ready to spring in multiple directions, each sentence a buoyant thread that can bear enormous weight. They’re what Beckett called “phrase-bombs.” They remind me of poems by Tristan Tzara, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Erich Fried, Tomaž Šalamun. Reading them makes me want to read Herder and Benjamin, Wittgenstein and Novalis.

Translating kochanie is thus an especially daunting challenge, one that Nissan meets superbly. Take, for instance, “an die kreisauer hunde”/ “to the dogs of kreisau,” which begins:

o der dorfhunde kleingescheckte schar: schummel

schwänze stummelbeine zähe schnauzen am zaun

English cannot directly match the marvelous run of “sch”/”schw”/”schn” sounds, the pair of “ä” sounds, the four toothy “z”s, or the two “au”s (which are amplified with another two in the next line). Nissan nevertheless finds a way to seize the essence of hearing the German:

o throng of piebald village dogs: frumpy tails

and stump legs, muzzles brazen at the fence

His choice of “throng” provides assonance with “dogs.” He departs from literal meaning by translating “schummel” with “frumpy,” which works because it enables a near-rhyme with “stump.” Likewise, “brazen” may not be precise for “zähe,” but it is a superior translation because it conveys the mood and flow, the “z”s in English approximating those in the original. Placing “brazen” after “muzzles” not only fulfills the meter but expands the mock-heroic sensibility of what – on the surface – is an ode to a pack of mutts in a hamlet.

Nissan makes similarly clever decisions throughout, remaining true to the form, register, and feel of Wolf’s words where the prosody of German cannot be replicated in English (his two-page afterword would make a fine primer for a coursepack in a seminar on translation poetics). He gives us “billowing bark” for “bellen in wellen,” “plucky plod” for “tapferes stapfen,” “we dare to question / we wear …/ embroidered…” for “wir fragen geschickt / wir tragen gestickt,” “we talk up a pace / we cheat in the chase” for “wir sagen geschickt / wir jagen gespickt.” He finds idiomatic matches: “dorfauswärts zuletzt” yields “ditching the village at last,” “eine beifahrerin” is “a girl / riding shotgun,” “geschlossne stellwerk” is “boarded-up signal tower.” Wolf’s poetry being akin to Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s Tête Dada or Hannah Höch’s photomontages, Nissan has his work cut out for him with Wolfian neologisms such as “schwesterntiere,” “fegewasser,” “nebelvoliere,” and “zischgebet.” These Nissan crafts as, respectively, “furry nurses,” “purgatorrents,” “haziary,” and “dimmer-time blessing,” each fitting easily into Wolf’s poetic landscape, each carrying forward the poem’s logic and intent. I chuckled in admiration as I read these – I want all the poetry I read to elicit that response. I loved trying to track Nissan’s tactics as he solved for Wolf’s impish wordplay. For instance, initially I balked at his selecting “kitsch” for “tand” (I might have used “bric-a-brac” or “knick-knack”), until I realized how that allows for a near-rhyme with “sits.” Likewise, I wondered at his choosing “tight” for “emsig,” before realizing that doing so supports a rhyme with “site.” Almost never did I truly query, let alone resist, any of Nissan’s choices. “Plat book” feels more natural /less elevated to me than “cadastre” as a translation for “Flurbuch, and “foolhardy” or “daring” seems more effective than “foolish” for “tollkühnem.” “Märchen” should be “fairy tale,” not “fable.” But now I am starting to sound like another definition of the Beifahrer – the back-seat driver! A handful of quibbles only highlights how well the translator has taken justifiable risks and delivered a resonant recasting of the original.

Further evidence of Nissan’s prowess, and the power of Wolf’s original, is in the devastating longer poem “wald herr schaft” / “wood lord shaft,” based on Titus Andronicus. The poem returns to Shakespeare’s original, not the expurgated versions (silence imposed, gaze averted) from intervening centuries, bringing its sexual violence and mutilation into sharp focus. Reading this poem hurts, as it must. “verschworen fickrig und verschwistert” loses none of its ominous pulse with “the fuckrich bloodlines here conspiring.” Nissan’s translation of “geschichte ihre gotenhoden antithetisch/ aufgebockt zur jagd…” is ingenious: “history their gothnads bristling jacked / up for the hunt …” “striemen” is “stria” in Nissan’s translation, not what I expected (I would have less felicitously supplied the pedestrian “welts” or “weals”), and yet utterly apposite. Nissan is the agile translator who can dance along with Wolf’s inventive zigzags, when she coins words such as “stottertrog” and “drecksaum.” I can only imagine that “wald herr schaft” / “wood lord shaft” will be anthologized.

Wolf recalls the enormous impact that Shakespeare had on German letters in the 18th- and 19th-centuries, and suggests how Anglophone understanding of the Bard can benefit from German perspectives. More generally, her multilingual dexterity helps English-speakers better comprehend the ideals of the tenacious fantasy known as Mitteleuropa, imbricated as it is within what Daniel Snyder calls “the bloodlands,” reminding us of shared philosophies, common failures, and deep strata of history. Her work can be seen as advancing the projects of the émigré artists and scholars from the last century, those re-establishing the Bauhaus in Chicago and founding The New School in New York City, for instance, and independent spirits such as Czesław Miłosz and Rosmarie Waldrop. Wolf’s serious play aims at rehabilitating language in the wake of atrocity – she carries on the legacy of Paul Celan, Ingeborg Bachmann, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, among others. As I listened to the Poles and Germans grapple with connection that fall day in Szczecin / Stettin, words with innocuous quotidian meaning – “oven,” “train” – came underbellied with a sanguinary recent past. Wolf’s trowel and brush reveal the underlying connotations (the stria, if you will) of those two words, and so many others. Nissan’s translation adds another degree of heft and acuity to the archaeologist’s tools. I hope these two poet-translators collaborate again, and that kochanie is just the first of a series of their works to be published by World Poetry Books.

Daniel A. Rabuzzi lived eight years in Norway, Germany and France, and has translated Norwegian (also Danish and Swedish), German and French in commercial and archival/scholarly settings. He has degrees in the study of folklore and mythology, international relations, and modern European history. He lives in New York City with his artistic partner & spouse, the woodcarver Deborah A. Mills. See www.danielarabuzzi.com and @TheChoirBoats.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, November 14, 2023