Following Threads and Leaving Traces: The Archive and Literary Translation (Part 1)

A Conversation between Breon Mitchell and Chris Clarke

A young person should be creating an archive, not simply preserving what they happen to do, but actually thinking about the sorts of things that we ought to know.

This conversation took place by phone on November 6th, 2023 in preparation for a panel entitled “Places & Traces: The Translation Archive” at the ALTA conference in Tucson, Arizona. Literary translator and scholar Chris Clarke reached out to Breon Mitchell, also a literary translator as well as the former director of the Lilly Library at Indiana University-Bloomington, and they had a wide-ranging discussion about their experiences with different translators’ archives, about Breon’s work establishing the unparalleled translation archive at the Lilly, and about issues facing scholarship and access in this domain. Breon kindly offered some practical suggestions on how translators can conceive of their own archive, and tips on how to successfully build their own.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity.

Chris Clarke: During my first visit to work in the collections at the Lilly Library in Bloomington in 2016, one of the most interesting things was getting to look at something that we don’t see to quite the same extent anymore, and that is the translator’s working library. In the Barbara Wright archive at the Lilly, what I found as interesting as her correspondence and notebooks was her working library, which gave a good idea of what serious translators needed to amass in their home library to be a good translator, prior to the internet.

Breon Mitchell: I don’t know if you came across it when you were there, but we have Cid Corman’s papers and library. And he translated a number of things, but he very heavily annotated almost every book that he owned, and that meant that he retranslated many of the translated books that were given to him by friends. You can see any number of translated books and periodicals where Corman has gone through and sort of redone them and corrected them in ways that he found better. That could make for an interesting study, a translator who obsessively responded to other people’s versions of every work.

CC: Perhaps we should look into a Posthumous Collected Private Retranslations of Cid Corman.

I have a lot of dictionaries and reference materials at home, and I’ve found that depending on what period I’m working on, I need different materials. I think I’m maybe at the tail end of the paper dictionary curve. If I’m working on texts from the the late 19th or early 20th century, I want to use my turn-of-the-century Larousse instead of my Petit Robert for French, for dated words or slight shifts in meaning that occur over the years, that sort of thing. It was very interesting to see what Wright had put together, non-fiction reference books of all sorts.

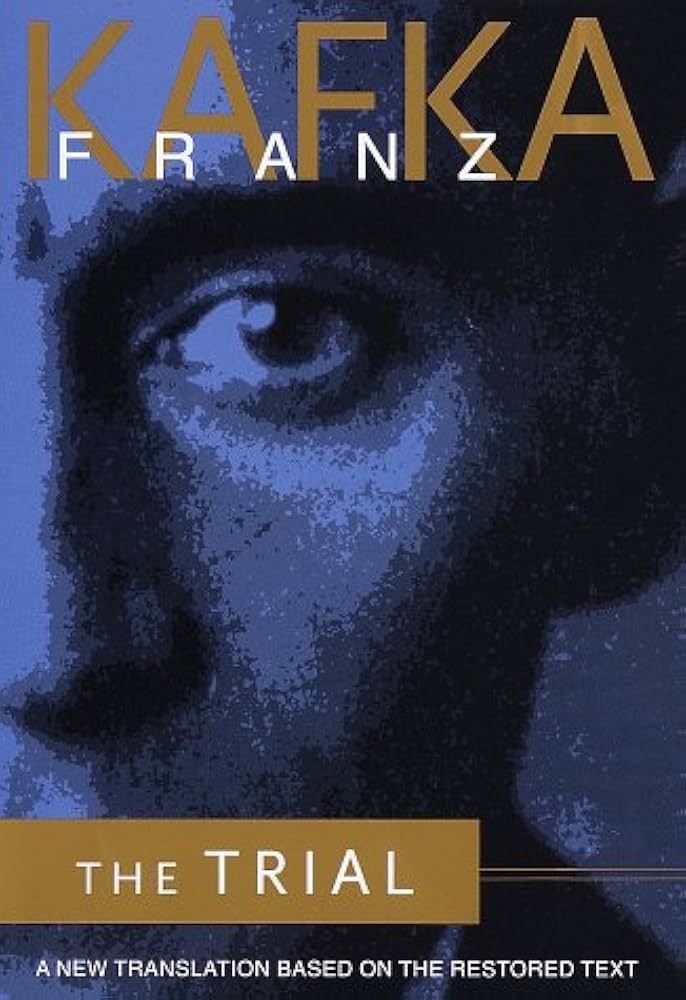

BM: When I was translating Kafka’s Trial, I used legal dictionaries from the time he was writing, and indeed, they included some terms that seem to have disappeared in the meantime, but that he actually used in the novel. I thought that was worth doing and worth knowing about.

CC: You spent many years building this collection of translator’s papers for the Lilly. How do translators’ archives come together? Or, on a smaller level, how do a translator’s own papers become a collection that can become part of such an archive? As I’ve told you, next month at the annual conference of the American Literary Translators Association, I’ve co-organized a panel on the uses and practicalities of scholarship in translation archives. Our co-panelist Daniel Hahn, from what I understand, has been “putting his papers in order,” and I really look forward to hearing from someone as well published and well regarded as Danny about what he’s doing, in practical terms. It’s a big step, right? For many of us, once you’re getting closer to retirement, perhaps you get to the point where you look back through all the years of papers you’ve held onto and say, Yeah, I should do something with these. But what do you do when you’re in your thirties and you’re not very well published, you haven’t had the long, prestigious career, and don’t know if you ever will?

Many writers and translators are bashful about their work, too. You spoke to that a little bit in the previous article you published on translation archives. The question of who should be preserving materials, and what it is that they should be preserving. You mentioned to me, when I first visited the Barbara Wright collection at the Lilly, that when you asked Wright for her papers, she had basically said, Well, who cares about this stuff? Translators are often rather self-effacing, I think it comes with the territory in a way, this kind of bashfulness. And earlier in our careers, we don’t always have very positive expectations of where all the work is leading. For most of us, we’re going to be at this “Who cares?” stage for a long time. I’ve never thought I was important enough that anyone would ever care to look through my old work, and I suspect that’s pretty typical. What do you recommend, as far as telling younger translators, those earlier in their careers or without the long list of awards, how they might approach this?

BM: One thing, for a younger translator, in terms of their papers and so forth, is that it’s really the perfect time, particularly if they’re translating living authors, but even if they’re not, for them to develop the sorts of things that they themselves would like to see if they were trying to study some translator’s life or works. This means that you can, if you’re thinking about it, generate a lot of extremely interesting material. I thought about this when I was a young translator, because I was always a collector and interested in archives. I made it a point, whenever I did a translation and the author was alive, to make sure that I contacted the author; and not only that, to come up with lists of questions and exchanges, and if I could, correspondence, in order to build up some sort of a sense of what had actually happened during the translation process. I kept more drafts of my translations, probably, than most people would. But now, I always want to say to people, Don’t throw things away! Keep them, and if they end up going to an institution, you can tell them, look, I’ve kept everything. This is what Barbara Wright did, but she said, you can throw away anything you feel will not be of any interest to scholars or students. She left everything up to me, totally. She just gave me everything she had and said, I trust you to keep the things that should be kept. And if you start out when you’re young, you can create all sorts of interesting information simply by asking questions, following through, keeping records, all sorts of things like that. That’s what I feel: a young person should be creating an archive, not simply preserving what they happen to do, but actually thinking about the sorts of things that we ought to know. So many translators are, as you say, bashful, but they are also hesitant to ask questions of an author, or they’re hesitant to talk with other translators about problems they’re having. They don’t want their author to know that there is a phrase that they didn’t really quite understand, because they’re worried. Oh, what’s the author going to think if it’s some phrase that I don’t know that it turns out I should know? It’s much better to ask the questions and face that possibility than to not ask the questions and miss out.

I’ve been in touch recently with Sten Nadolny, a German author I’ve translated a novel by, and recently, I was translating another book by him with my wife Lynda. I was talking about archives, and I asked him about his own papers as a writer, what he was doing with them. He wrote back and, in a very nice letter, he said that in going through his manuscripts and going through everything that he had as a creative writer, he felt that the thing that revealed the most about himself, about what he was writing, why he was writing it, and what he wanted it to be, was to be found in his exchanges with translators. He said that his correspondence with translators had been the only time, in many cases, where he expressly told somebody what it was he was wanting to do, trying to do.

CC: Fascinating! I can see that, it makes a lot of sense.

BM: For him, it was true, and that correspondence was partly with me, I know.

At the Lilly Library, we have Leila Vennewitz’ exchange of letters with Heinrich Böll, for example. Well, this is an exchange of three hundred letters over the years, from the first works of his to be translated all the way through to the Nobel Prize. She translated everything. Three hundred letters, about two hundred of them are hers, and a hundred of them, I think, are Heinrich Böll’s. The point is that for anybody who wants to study Heinrich Böll… I can’t imagine anybody writing a biography of him and not looking at this material. But I also can’t imagine anybody studying any one of these works who wouldn’t find in his letters to Leila Vennewitz, and her questions to him, the sorts of insights that are truly unique. And they couldn’t find them anywhere else. That is exactly the sort of scholarship that interests us, about the whole process of literary translation, but also about the original author and what the author was up to.

That’s why I find translators’ archives so interesting, and that’s just one part of it. Obviously, the letters between the translators and the authors, everybody can see that this would be a particularly interesting thing. I remember, with various authors, discussions about what to call their novel in English: what to do about a title in German, and what would work best in English. And there were at least two or three cases in which authors told me that the English version was the title they had always wanted for the work, but they couldn’t give it that title in German for specific reasons. Often, part of the reason was that there was already a novel in German with a similar title, so it was out of bounds for them. But in English, that’s the title they actually wished they could use. These things get revealed in letters.

Sending a list of questions, I always do this because I’m interested in being sure I’m understanding and getting things right. What I often do is ask the author to paraphrase something. And that is interesting, because generally, and this was happening with [Uwe] Timm, another German author I was translating, he would go into a paragraph or two discussing what he was trying to say, and paraphrasing it, and why he wrote it that way. You get a lot more than just a yes or no answer to something.

To return to the question of what a young translator should do with their archive, it’s to not only preserve it, but create it. Have in mind all of these things. Think a hundred years from now, what would people coming to a library to study translation or a particular work of literature, what would they want to find? And maybe you can keep, or even produce what you think they’d want to find.

CC: A consequential question that keeps coming to mind for me is simply one of supports, of materials. When I began translating, not quite fifteen years ago, I had the romantic notion that I was some sort of Hemingway-like figure, and I needed to do all of my work with a pen. So I used notebooks, and I did everything, from the scruffiest first draft to a near-final draft, in notebook after notebook. I still have all of those, and that’s great. However, it was also very time consuming. It always took me an extra few weeks to type it all up afterwards. Since then, because of time considerations and also some long term problems with my hands, I have shifted to doing most everything directly in a word processor, as most translators do. And yet this doesn’t leave the same sort of traces as other methods did. Now, where Barbara Wright’s archive is full of paper drafts and loose sheets and notebooks and actual letters and postcards, ours is instead going to be one made up of an infinite number of poorly organized, confusingly-named drafts, and by emails scattered throughout different accounts. Sometimes, for me to find a certain draft of a certain book, I have to go back two, three, four, even five laptops, because not everything has made it onto external hard drives that can move from one machine to another. Email accounts become inaccessible, too, often when moving from one job to another or for technical reasons. So what can we do to make this shift from the paper age to the digital age, when the archive is still largely one of paper?

BM: Right. It’s a sad fact that we’ve lost all of that beautiful clutter a translator used to have in their papers, and now we do tend to get maybe a series of three or four printouts with a few hand corrections on them. That’s the best we can do. There are two things. First, when it comes to the drafts of translations, what I do, and I would hope that everybody might do, is to have at least a sense of the three or four major stages their translation has gone through, and actually print it out at each of those stages. They may not need to, because they can just keep correcting and going over it every day and changing it, but at some point, four or five times at least, stop and print it out. And I would encourage people, once they have it printed out in a certain draft, to just take a little time and go over one of the drafts and do that with a pen or pencil and make the sort of emendations that you would make automatically with the computer. It’s another way of thinking about how to revise your own translation. And as you and many other writers have said, sometimes there is a difference in the feel when you’re holding a pencil or pen, and have your translation in front of you on a sheet of paper, and it can change which changes you make. That sort of touch, it can be not only fun, but inspiring to work in that way. And then I go back to just typing in the changes, where nobody will ever know the sorts of things I was thinking.

CC: I do always produce at least two of those, on paper, even if I might do my first three or four drafts directly on the computer. I then often exchange manuscripts with a colleague of mine, she’s also a translator from French. That’s one of the greatest deals that we translators can be lucky enough to have: who could you ever afford to hire, who would have the expertise to close-read your translation against the original and make detailed comments for an entire book. We can’t afford to hire someone to do that on what we’re getting paid for the translation, but if I do it for her books, she does it for mine. When she sends me a manuscript, I print it out and I go through it with a red ink pen, and when she sends me suggested edits and notes on one of mine, I print out her commented version and go through all of that in ink as well.

BM: Yeah, that’s wonderful. These are very good things to mention in a workshop, or to other people, they are ideas that other people may not have thought of. And it’s a very good idea, actually. Not everybody has access to another translator that they can really have that relationship with and do that sort of exchange, but say you don’t have, if you start thinking about it, you might think, well, actually, I could see contacting so and so. You could go through your list of friends and people you know, and think, well, maybe we could do an exchange like that.

I’ve been doing a lot of work for many years with Samuel Beckett, particularly bibliographical work, and because he did a lot of translation, I tend to think about a person who does self translation and is translating other things as well. But as soon as he could get away from the translations he was doing just to earn a little money so he could live in Paris, he stopped doing any translation for pay, except for the work of a few friends. Still, he was doing translation for pay at one point, and he was asked to vet others’ translations that were coming out in periodicals in Paris. He said, as we all know, that to vet a translation is probably as much or more work than to translate it yourself. He constantly said, I could retranslate this more easily than I can go through it for changes. And so this is the way that a friend can help in this situation. It’s a lot of work, and it’s a mutual exchange, so it’s actually a rare situation, probably, but I like the idea, and it’s always worth having in mind.

CC: And it produces a paper draft, too, which was my initial point for the topic at hand. I do end up with at least one further paper draft for each book, after that. Before I send the final translation to the publisher, I always do a read-the-whole-damn-book-aloud-in-one-or-two-sittings draft, where I sit down and read the book to myself in my indoor voice, from beginning to end, with my red marker out, and that’s where you catch those last little itches, the that-thats and unwanted repetitions and those sorts of things.

BM: Exactly.

CC: So that leaves a paper trace behind as well.

BM: Speaking of Beckett, Barbara Wright did translate Beckett’s Eleutheria, which is interesting, and I’ve never looked at that translation closely, but I should at some time. There are such riches in any individual translators’ archive. There is so much still to be learned and so many fun things to be discovered by looking at these archives.

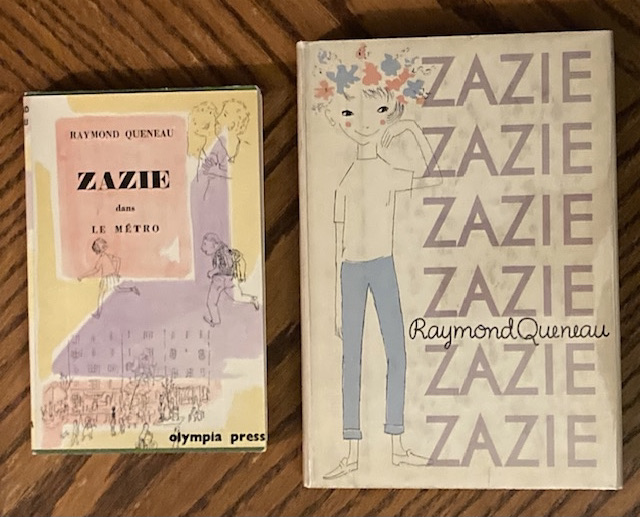

CC: To your comment about Beckett saying that vetting a translation, or fixing someone else’s translation that isn’t working, is often more work than doing it from the scratch, this reminds me of a letter I read in the Wright archive in Bloomington. There’s a run of letters to Barbara Wright from Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press, asking her to “fix” the early translation that Jack Kahane did of Raymond Queneau’s Zazie dans le métro, to which she responded, Well, to be quite honest, it would be a lot easier to just start this book over again. And she declined to intervene, and later retranslated it herself from scratch.

BM: This is absolutely, absolutely true. And these are the things you see in the archives. You encounter this sort of situation firsthand, what translators and authors think.

This conversation will be resumed in Part Two, coming to Hopscotch Translation soon.

Breon Mitchell is a founding member of the American Literary Translators Association and served as President in its early years. His major translations include Franz Kafka (The Trial), Günter Grass (The Tin Drum), Heinrich Böll (The Silent Angel), Siegfried Lenz (Selected Stories), Uwe Timm (Morenga), and Sten Nadolny (The God of Impertinence). As Director of the Lilly Library at Indiana University he devoted himself to preserving the literary archives of major English-language translators both here and abroad.

Chris Clarke is a literary translator and scholar. He currently teaches in the Translation Studies Program at the University of Connecticut. His translations include books by Raymond Queneau, Éric Chevillard, and Julio Cortázar, among others. He was awarded the French-American Foundation Translation Prize for fiction in 2019 for his translation of Marcel Schwob’s Imaginary Lives, a prize for which he was also a finalist in 2017 for his translation of Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano’s In the Café of Lost Youth. His translation of Raymond Queneau’s The Skin of Dreams is newly out from NYRB Classics.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, October 22, 2024