Navigating Liquid Geographies: A Conversation with Eleni Kefala

An interview by Peter Constantine

I’m not sure if I’ve ever told you this, but I was intrigued to see how you would handle the various Greek registers in the book, particularly my grandfather’s hybrid idiom.

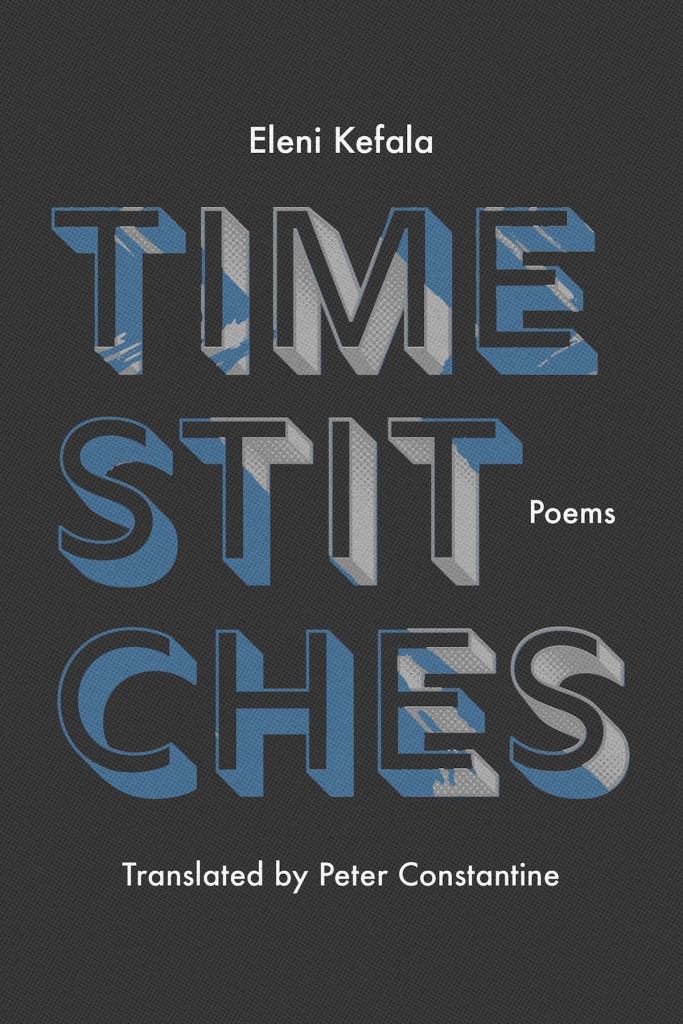

Eleni Kefala is a Greek Cypriot poet who lives within a number of cultures, languages, and language variations, a poet who is particularly fascinating to translate because of the exhilarating challenges of the shifting language and dialect in her work. Her book Time Stitches was the winner of the State Prize for Poetry in Cyprus, and my translation, published by Deep Vellum Press in 2023, received the Elizabeth Constantinides translation Prize of the Modern Greek Studies Association. The book follows intertwining paths of standard and non-standard Modern Greek, alongside instances of Cypriot dialect with its melodious registers and sounds.

The poem cycles that compose Time Stitches connect to different places and historical times, stitched together in intriguing patterns. Kefala has personal connections to each place and its culture and history. In one of the poetry strands, Cyprus and a Cypriot villager of the early twentieth century take center stage; a second strand narrates a moment in history at St Andrews Castle in Scotland, where Kefala now lives and teaches at the University of St Andrews. The Byzantine and Aztec Empires emerge in a third, which follows the conquest of Mexico from the first portents of doom to the moment Montezuma’s empire falls to the Spanish conquistadors and their indigenous allies. Kefala’s academic field is Latin American Studies and Comparative Literature; one of her recent monographs, The Conquered: Byzantium and America on the Cusp of Modernity, examines Greek and Nahuatl laments for the fall of Constantinople and Tenochtitlan at the dawn of the modern world, focusing on similarities and differences in the manifestation of cultural trauma and collective memory in two distinct civilizations. In Time Stitches we also encounter the moment that Rodrigo de Triana, a sailor on Christopher Columbus’s ship La Pinta, sets eyes on the Americas, a moment that would eventually lead to cataclysmic consequences for many native populations of North America.

Eleni and I met for the first time in Toronto in October 2022, just before the publication of Time Stitches, and spent the day at the Royal Ontario Museum strolling through the Greek, Etruscan, Roman, and Byzantine exhibit halls. We spoke at length about Greek and Hispanic literature, the native cultures of the Americas and Greece, and the Maronite villages of Cyprus, where Sanna, a form of Cypriot Arabic, is still spoken by some elders. Eleni Kefala is also a translator, mainly of Spanish American literature into Greek; she has translated, among others, works by the Argentinian author Ricardo Piglia, the Mexican poet Rosario Castellanos, and the Argentinian poet Alejandra Pizarnik. Wanting to know more about her views on her own poetry, on translation, and her thoughts on how I had translated her, I initiated the conversation that follows.

Peter Constantine: When I first read Time Stitches I was struck by the interweaving of what seemed to me the strands of a fascinating plot. In fact many strands of many plots. I felt that the poems, read in sequence, brought those strands together in a rich and unexpected, novelistic way.

Eleni Kefala: I’m delighted you mention this because Time Stitches relies strongly on the reader, who’s tasked with putting the jigsaw puzzle together. But unlike the well-known game, there is no single pathway to accomplish this. I often imagine the book’s structure, its scaffolding, as a shattered piece of glass or pottery. The reader must recreate it through multiple readings. Of course, not all readings are—or even can be—the same. Personal and cultural perspectivism is always crucial. Think of decorated Greek vases or water jars that tell a story, often a myth. It could be the Amazons fighting the Greeks, Oedipus and the Sphinx, the Judgment of Paris, Theseus and the Minotaur… Now picture a crazed archaeologist smashing many of those vases. All that remains are fragments of several plots. How do you reassemble those stories so that they speak to each other, while still being open to new meanings and possibilities? The job is shared by the author and readers alike; it’s a collaborative effort by many ceramicists to reconstruct the text’s body by connecting what you’ve referred to as “many strands of many plots” in a variety of unexpected ways. Even better, we may consider it as a continual act (or should I say art?) of translation, or even mistranslation (many interesting things might result from this), with each reading bringing new meanings to the broken synthesis. Many ancient vases actually tell the story of Hercules’s twelve labors, one of which was to kill the nine-headed serpent, the Lernaean Hydra. The water monster, which lived in the marshes of Lerna in the Peloponnese, reportedly terrorized everyone in the area, prompting Hercules, the ultimate Greek hero, to intervene. Every time he cut off one of the Hydra’s heads with his club, however, two more grew in its place, making the monster’s killing appear to be an endless labor. Let’s keep the image of multiplying heads for a moment, but consider it in a positive light. I’d like to think that every time a reader cuts one head off Time Stitches by reading a poem, many other meanings and possibilities emerge. This is the concept underlying the book’s architecture. I’ve always liked brevity in poetry. How do you say more with less? This question, which I owe to poets and writers like Cavafy and Borges, guided my writing of the book. One reason poets continue to write, I think, is that they never quite manage to articulate the single poem they have in mind, that ultimate, final poem. We create variants, translations of the poem, but never the thing itself. Poets are essentially translators of their own ideas and those of others; they are translators of meanings. I hoped that the shattered “novelistic” synthesis of Time Stitches would let the act of translation take center stage, allowing readers to continue the process of meaning-making long after they turned the final page.

PC: That is a fascinating thought, that you, and I, and our readers are all sharing in an act of translation in such similar and such different ways as we encounter the plot strands. One of the strands I found myself particularly drawn to is centered on rural Cyprus, its language, and the biography of a young Cypriot man.

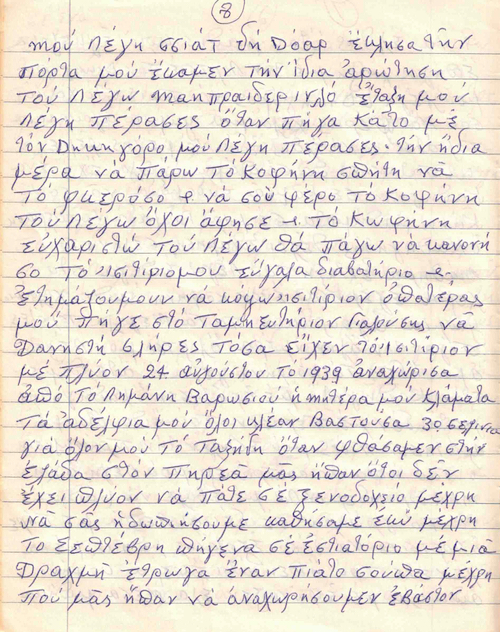

EK: The plot thread you mention, unraveled in twenty-six fragments, has a special place in the book, and is the basis for all the other threads and poems. Born in 1919, the anonymous Cypriot man from Melanagra, a hamlet near Gialousa, in the remote rural section of the Karpas peninsula at the northeastern end of Cyprus, had barely finished primary school. His family could not afford to send him to secondary school, so his written language was a curious blend of the standard Greek he learned in primary school and the Cypriot dialect of the time, which was and still is rarely written down. His writing was riddled with errors, and he seldom spelled a single word in the same way twice. Spelling was certainly a challenge for someone like him in a language like Greek, which has, for example, not one, not two, but three different letters and three distinct digraphs for “i”; they also had to employ diacritics back then, which we now only use for ancient Greek. For him and others of his generation with similar education, writing down this hybrid register was already an act of translation, and their approach to the written language was often visual, as if they related to it in a physical way. The book plays with this relationship between word and image; few terms in this plot strand retain their spelling throughout. He keeps writing πλοίο (plio), for example, the Greek word for “ship,” with the wrong “i,” replacing the digraph οι with υ, perhaps because the latter resembles the shape of a boat or the movement of waves (another recurrent theme in Time Stitches). I’m very much drawn to the idea of the physicality or materiality of language, as well as to the fact that poetry, like life, is present all around us in various shapes and forms.

I’ve mentioned that the twenty-six fragments where we hear the voice of the Cypriot man are the womb from which everything else in the book originates. All the other plot strands and poems emerge from it in a centrifugal manner. A word or a phrase that the man says serves as a springboard for the poetry that comes before or after it. In this constant to and fro of meanings and contexts, things change, often as a result of mistranslations. “Higher school,” for instance, is mentioned by him when he speaks of his family’s inability to help him complete his studies. The modern Greek term for secondary school is “gymnasium,” but in ancient Greek the word had the same meaning that it does in English. The poem that follows this fragment is titled “Gymnasium,” but it breaks from the current Greek definition of the term, returning to its ancient roots as a place of physical training. In this way, Time Stitches constantly shifts between temporal, spatial, linguistic, and conceptual contexts. Like the Cypriot man’s spelling, meaning is continually recast in the book, becoming malleable and fragile. Poetry is not solid ground but sea, an ocean of movement and change. Time Stitches, in a way, re-enacts the mechanism of poetic writing. Poetry works with metaphor (a word that originally meant transport), with each concept, image, and meaning carrying us to other concepts, images, meanings, and so on. Poets are both translators and carriers of meanings, two words that are essentially synonyms.

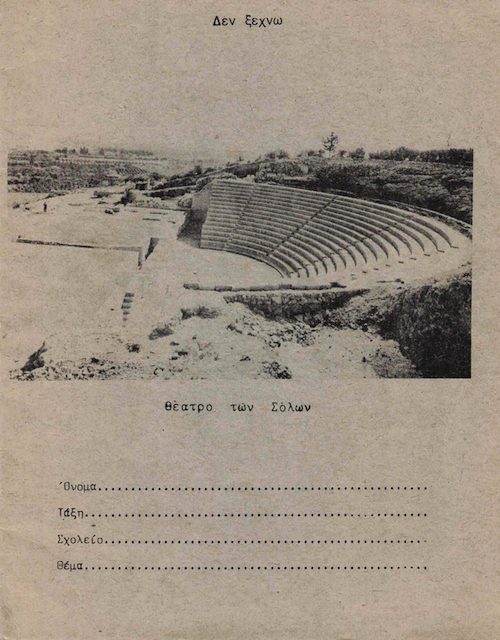

Michalis Hatzinikola was the name of the Cypriot man, my mother’s father and the youngest of eight siblings. On the eve of World War II, he arrived in London as an economic migrant. He was twenty years old when he left Cyprus, then under British rule. He lived and worked in the British capital until 1944, when he had to enlist in the British army for three years. He then spent over three decades working in England before returning to Cyprus permanently in 1973. A year later Turkey invaded the island, and he was soon forced to flee his home in Gialousa: this time as a refugee, to the south. On weekends we used to visit him at the refugee settlement. He was always telling us stories about his time in England, especially wartime memories, sometimes from London, sometimes from Gialousa, where he had lingered for two years under Turkish occupation, before heading to the south with his sick wife. He would tell us the same stories over and over again. Some of them captured our imagination more than others, like the one in which he was crossing the Waterloo Bridge at midnight after finishing work at the restaurant, when a Nazi bomb exploded in the river, drenching his clothes. No wonder my brother and I thought we had a homegrown Odysseus. Thankfully, those Sundays were not simply filled with grandpa’s stories. He would take my hand and walk me to a neighboring kiosk to buy me the latest issue of Mickey Mouse. One day, I must have been about ten, he started telling us one of his stories again, but I couldn’t wait to read my comics and didn’t want to make him sad either. “Grandpa,” I said, “why don’t you write down your stories so that I can read them?” And so he did. He methodically completed four A5 exercise books, filling every blank spot from end to edge. He must have wanted to avoid wasting paper. This is how Mickey Mouse saved my grandpa’s life. I’m grateful to Mickey, Donald, Uncle Scrooge, and company. Grandpa’s stories have survived my childhood thanks to them.

PC: What drew me to your poetry was that linguistic mix of familiar and not-so-familiar Greek, the echoes of different Greek registers. I tried to re-create an impression of your style by using dialect moments from different British and American regions.

EK: I’m not sure if I’ve ever told you this, but I was intrigued to see how you would handle the various Greek registers in the book, particularly my grandfather’s hybrid idiom. As a poet, I was always concerned that the language’s nuances would be carried away by the vitality of an international language like English, or that they would devolve into folklore or a somewhat meaningless jargon. That’s one of the reasons I was so pleased when you considered translating Time Stitches. I knew the book was in excellent hands because I had already seen some of the ingenious solutions you’d presented in the context of other projects. Besides, being a polyglot and a terminal speaker of Arvanitika [a dying autochthonous language of Greece], you have a rare sensibility for the complexities and anxieties of minor languages. No need to say that I found your solution extraordinary. Working with dialectal materials from diverse parts of the English-speaking world allowed you to breathe fresh and recognizable echoes, undertones, and connotations into the text, as you helped it settle into its new home. You did this without masking grandfather’s idiom by anchoring it in a specific British or North American sociocultural habitat. It would have certainly been odd to hear him speak in Texan or Glasgow accents! You’ve managed to keep the host language’s affinities while avoiding its constraints. That was a fantastic idea, wonderfully executed.

It was critical to re-create the subtleties of the various registers in the translation, not least because in certain parts of the original the use of Cypriot Greek plays an important role in the book. Since Antiquity, Greek has been a dialectal language in the sense that it has always consisted of several dialectal systems. If it were a river, it would be made up of multiple creeks and brooks. Navigating this liquid geography of past and present regional dialects may not always be easy but is definitely rewarding. Working with medieval Cypriot for the purposes of my latest poetry book Direct Orient, which will be published in Athens this summer, reminded me of the remarkable similarities shared by the dialects of Crete, Cyprus, and the Dodecanese (a group of islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and eastern Mediterranean). No form of standard Greek, or koine, has ever been able to entirely dry up the creeks and brooks of the Greek language since Hellenistic times, stretching back to the fourth century BCE, except for the current koine. But there are still streams like the Cypriot dialect that obstinately refuse to go underground, resisting the homogenizing forces of state institutions and other ideological, political, and social factors in both Greece and Cyprus. It’s fascinating to witness a revival of interest in the usage of dialects and local idioms by new generations of authors and poets in the two countries in recent years. Of course, it is no surprise that this “dialectal turn” is occurring at the height of globalization. Aside from replenishing a language’s mainstream river, dialects can do a lot of interesting things, such as rooting us in the historical, cultural, and emotive intimacies and attitudes of specific peoples and places. Time Stitches enjoys both navigating the main river and riding the creek known as Cypriot dialect. I’d like to think that the meeting of the two Greek varieties puts the language’s historical and cultural depth in perspective. Among the poetry strands there is a short poem in ancient Greek that reproduces, in the form of a haiku, Heraclitus’s famous maxim, “time is a child playing a game of draughts.” Language, meanwhile, is a form that that child, time, takes in the lifespan of humanity.

From grandfather’s hybrid idiom in Time Stitches to the use of Greek dialects in the bits of Direct Orient that read the Epic of Gilgamesh through the themes, rhythms, and textures of Cypriot and Cretan Renaissance poetry, there’s a stubborn insistence on making room for the Greek language’s creeks alongside the main river. I say “stubborn” because such projects require more participation from the reader. They also demand significantly greater work on the part of the translator, who must transfer the intricacies of the source language into the host culture. Of course, it would be much easier if we always wrote in a homogenized language, whether it is an international language like English, or the standardized variety of a given language like Greek. This would no doubt make the texts more easily accessible and translatable, allowing them to be exported and read globally with greater ease. Latin American soaps, for instance, serve this function by frequently using a more “neutral” Spanish. But I prefer to negotiate more fluid environments in poetry.

PC: You are an Associate Professor of Spanish at the University of St Andrews in Scotland and some of your research focuses on transcultural projects involving Nahua and Pre-Columbian cultures. I was fascinated by the Aztec poetry strands in Time Stitches, the arrival of the ominous “pale-skinned strangers,” and your portrayal of Emperor Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, the poetry so distilled, pinpointing minute details. You are also a translator of British and Latin American poetry into Greek.

EK: True, translation has guided my work in various ways. I’m not so much referring to my translations of Hispanic and British poetry and prose, which I treasure but wish were more numerous (teaching in a British university, sadly, does not leave much time for that), but rather to my work as a poet and researcher. As you’ve pointed out, in my academic writings I take a comparative or transcultural approach, whether I’m reading twentieth-century Greek and Argentine literatures, examining modern urban space in Argentina using a variety of artistic media, or, more recently, probing sorrowful poems dealing with the fall of Byzantine Constantinople and Aztec Tenochtitlan. Such comparative, transcultural projects are intrinsically tied to translation because you are essentially searching for ways for them to connect and speak to each other, as well as how the meanings of one might shed light on or alter our perception of the other. This is especially true for projects like the one on the Byzantine and Aztec Empires, two worlds that had never been explored together. As one reviewer put it, such readings have the potential to make “the strange familiar and the familiar strange.” So, we’re back to the idea of the writer as translator and carrier of contexts and meanings. This appears to be a guiding principle in both my poetry and research. For many years, I assumed the two of them were separate, and it was only gradually that I realized they’d been talking to each other from the beginning. Consider the Aztec strand in Time Stitches that you mention, which includes the poem “Days of 1453.” Despite the fact that the title is strongly steeped in Greek contexts by echoing Cavafy’s “Days of…” poems as well as Constantinople’s fall to the Ottomans in 1453, the poem itself actually refers to the destruction of Tenochtitlan by the Spaniards and their indigenous allies in 1521. Even what appears to be securely fixed in specific settings can be uprooted in the shifting grounds of the book. Constantinople and Tenochtitlan first met in Time Stitches before they were conceived together in my research via a different route a few years later. However, it is clear that my poetry and academic work have been conversing at a subconscious level for some time, as is the fact that the concepts of translation and mistranslation, in their various forms and nuances, have driven my writings in multiple and often invisible ways.

“Days of 1453” is about Emperor Moctezuma I, who appears to be receiving a series of omens presaging the conquest of Tenochtitlan a few decades later. This is a willful misreading of the surviving literature regarding the omens that the Aztecs (who called themselves “Mexica”) reportedly witnessed a few years before the arrival of Hernán Cortés and his men. The omens are recorded in the Florentine Codex, a monumental ethnographic work created in the sixteenth century with the assistance of Nahua scholars and overseen by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. The work itself is the fascinating product of an early translation process in which two worlds, Nahua and European, met and confronted each other, as texts in Nahuatl and Spanish, shot through with hundreds of painted images, literally faced each other on the page. Interestingly, the Spanish text is often an approximation or synopsis rather than a faithful translation of its Nahuatl counterpart. According to the Florentine Codex, the omens emerged in the early sixteenth century under the reign of another Moctezuma, the so-called Xocoyotzin (meaning “honored young one”). This is the Moctezuma that ruled the empire when the Spaniards arrived. So, by misidentifying the earlier Moctezuma as the receiver of the omens, “Days of 1453” deliberately misreads the information provided in the Florentine Codex to allow for the meeting of the two doomed imperial cities, Constantinople and Tenochtitlan, as if the fall of one foreshadowed the destruction of the other, separated by a few decades and some seven thousand miles. There is, of course, a further level of intentional misreading in this poem, because we know that the omens were constructed after the fact as a colonial strategy to cope with change.

Meanwhile, Time Stitches’ plot strands, which deal with the conquest of America, zoom in on perspective. The poems alternate between the viewpoints on the one hand of Columbus, Cortés, and their men, and, on the other, of the two Moctezumas, the Nahuas, and the Taino of the Caribbean island of Guanahani, where Columbus first landed on 12 October 1492. The meeting of these disparate worlds with no common language resulted in mistranslations from the start, kicking off a long sequence of border encounters in which cultural values and knowledge systems were regularly reviewed and reassessed on both sides. Often none of them had the words to convey the other’s objects, customs, and ideas. This is something that has always fascinated me. “Days of 1453” highlights these moments of hesitation, the inability to articulate the unknown, and the effort to bring it into a familiar framework, to domesticate it, with whatever vocabulary was available. The omens are mentioned in the poem, but the information presented does not truly describe them. Instead, the poem is based on surviving indigenous accounts of how the Nahuas, including Moctezuma Xocoyotzin’s envoys, reacted when they first saw the Spaniards disembarking on Mexico’s Gulf coast in 1519. Because the Nahuas had never seen a caravel before, they didn’t know what to call it, so when they reported back to their emperor, they spoke of a small mountain floating in the ocean, drifting here and there without hitting the shore. They didn’t have horses either, therefore they referred to them as deer without horns, which were as tall as a house’s rooftop, carrying “pale-skinned strangers” on their back. The lack of vocabulary to accommodate the unfamiliar or incomprehensible was not the exclusive privilege of the Nahuas. In his letters to Charles V of Spain, Cortés describes the marketplace of Tlatelolco, Tenochtitlan’s twin city on the island of Mexico, as being far larger than anything the conquistador had ever seen in Europe. He claims that he chose not to name the goods on display both because of their sheer number and because he didn’t know what to call them. Perspectivism concerns Time Stitches’ numerous voices and characters as much it does the book’s readers.

Eleni Kefala’s forthcoming poetry book, Direct Orient, which will be published in Greek this summer, centers around a Cypriot immigrant woman who crosses the English Channel in 1973 and in Paris boards the Direct Orient (a cheaper version of the legendary Orient Express) to travel to Athens and eventually Cyprus. Set against the backdrop of Greek and world literature, the book explores, among others, the themes and textures of the Epic of Gilgamesh through Cypriot and Cretan Renaissance poetry, detective fiction, Greek folk poetry, film noir, and women’s poetry from Antiquity.

Peter Constantine’s recent translations include works by Augustine, Rousseau, Machiavelli, and Tolstoy; he is a Guggenheim Fellow and was awarded the PEN Translation Prize for Six Early Stories by Thomas Mann, and the National Translation Award for The Undiscovered Chekhov. He is Professor of Translation Studies at the University of Connecticut and publisher of World Poetry Books. His novel The Purchased Bride was published by Deep Vellum in April 2023.

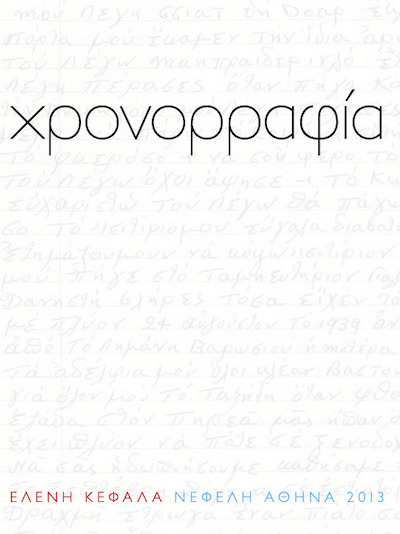

Eleni Kefala has published two books of poetry, Memory and Variations (Μνήμη και παραλλαγές, 2007), which was shortlisted for the Diavazo Literary Prize in Greece (first-time author), and Time Stitches (Χρονορραφία, 2013), which received the State Prize for Poetry in Cyprus. Eleni’s work has been translated into English, Italian, French, Turkish, Bulgarian, and Spanish. Eleni was born in Athens, grew up in Cyprus, studied in Nicosia and Cambridge, and currently makes her home in Scotland, where she teaches Latin American and comparative literature at the University of St Andrews.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, June 20, 2023