Translating Home: Review of A Cha Chaan Teng That Does Not Exist by Derek Chung, translated by May Huang

by Jenna Tang

How does the breath of poetry give life to an item that was once used for shelter and protection, but has since been completely forsaken?

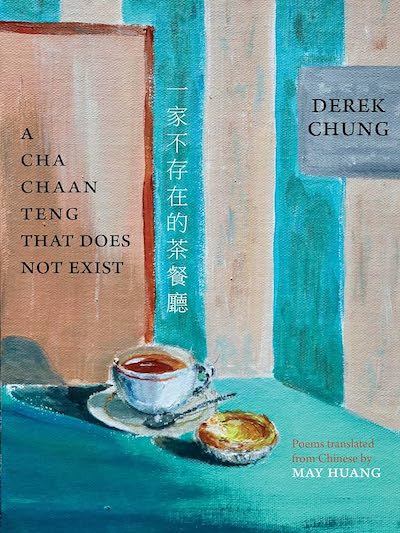

A Cha Chaan Teng That Does Not Exist, by Derek Chung, translated from the Chinese by May Huang. Zephyr Press, 2023, 112 pp., $16. ISBN 978-1-938890-28-4

I grew up in a Hakka neighborhood outside of the Taipei metropolitan area, and it was thanks to the many eateries, restaurants, and mamas’ kitchens that the community was able to thrive and grow. Now, whenever I return to Taiwan, having spent over 5 years in the States, I realize just how much these places have become centers of nostalgia for me. The tastes, smells, fumes, chatterings, and people come and go, rebuilding the dialect, language, and childhood memories. In places like this, it’s not just the spoken language that is preserved together with the familiarity of food, they also symbolize the sense of stability and homecoming for all of us who now live far away. A Cha Chaan Teng That Does Not Exist fully brought me back to this sentimentality and took me on a journey that is familiar yet unfamiliar to me.

A Cha Chaan Teng That Does Not Exist is a poetry collection by Hong Kong poet Chung Kwok-keung 鍾國強, deftly translated by May Huang. It meaningfully preserves the observations and landscapes of a Cha Chaan Teng, a fast service restaurant offering local food that portrays the multiplicity of cultural significances, including British influence and the existing Mandarin and Cantonese-speaking cultures. The collection includes a total of 23 poems, with Mandarin and English versions published side by side. The poems focus on a variety of food-related objects, household items that exist in the less noticeable, marginal spaces of a house that are meant to evoke a sense of longing, sentimentality, and remembrance.

Among the many poems, I was especially captured by “地板 Floorboards.” The following passage shares the breaths and sighs of the narrator while considering what floorboards, as part of a home, mean to him:

our son spreads out homework next to food that’s no longer hot

what do I leave behind what do I bring home?

between shriveled grains and stones I chew back and forth

as if nothing happened bones fall silently down the side of the table

the floor never told me just how much weight it can carry (21)

These lines discreetly personify the old floorboards, which are often left moldened and cracked and go unnoticed at home, implying the number of comings and goings they have endured. Given all that household items like these have shouldered and carried over the years, they define the coexistence of the humans living around them. The passage bears a sense of nostalgia, describing how it’s not just the people we know, but also items we know that age and change over time. Floorboards, in many ways, carry not just our physical weight, but also the experiences of moving, migration, and emotional turbulence.

I was likewise struck by the last lines of the poem “蝴蝶 Butterfly”:

then calmly

I slip you

through the door

remove

my weary

shoes

and stop longing for

someone far away

or myself (59)

Through the imagery of the butterfly, readers are left to imagine the colors, the movement, and the quietness of the scene. The tone indicates how longing in itself comes from absence and uncertainty, but also hope. The ample space left on the page, to me as a reader, seems intended to create a vast emptiness to establish a visual layer of yearning, so that readers are permitted to continuously imagine, to never stop clinging to that hope.

As we move along in the collection, the poem “離傘 Umbrellonely” comes with a homophonic title in Mandarin. 離傘 sounds just like 離散: separation, a sense of departure, stories that have left their traces but have since become history. For instance: “your dark green coat slipped off slightly/ showing the bent bones of an umbrella / as if in this drizzling rain you still wanted / to fish for stories long gone” and, later, “does a cheap plastic handle / still miss the first warm touch of a hand?” (75). Both show the disposability of a used, broken umbrella, which evokes a sense of desolation. What does it mean to visualize solitude, staticity, alongside longing? How does the breath of poetry give life to an item that was once used for shelter and protection, but has since been completely forsaken?

“尋找一家麵包店 Searching for Bakery” is another poem that tackles a sense of loss in the city, juxtaposing the constantly changing landscape with the one that stands firmly in the poet’s memory of the familiar yet estranged urbanness:

Yesterday I didn’t know

How far I’d have to walk

Until I found a place to crash

I know

A foreign place

Will not become familiar overnight (79)

Regardless of the size of the city, things and people transform over time. The experiences of migration produce alienation, that faltering emotion which questions our familiarity with the present, the past, and the days to come. As one migrates, homecoming means looking back – having a part of us dwell in the past but at the same time, immersing ourselves in the present in a new way to engage with our surroundings. That constant search for familiarity also stands for our consistent search for home.

Finally, the signature poem of the collection, “一家不存在的茶餐廳 A Cha Chaan Teng That Does Not Exist,” focuses on bringing the meaningful presence of Hong Kong’s signature Cha Chaan Teng to readers. A place with food attracts all kinds of eaters and therefore becomes vibrant with stories, which lurk between the lines of this poem:

With indents lining the rims

As if concealing different stories

Flipping through a stack of bills skewered together

The confused waiter no longer knows

Where to begin (33)

What does it mean when local culture is vibrantly knit together by a place for dining? Cha Chaan Teng is not just a place for people to eat, but also a location for encounters, nourishment, gathering, and forming a sense of community. It swells with the sounds, smells, and tastes of the food and language that evoke a sense of belonging, of home.

Derek Chung’s poetic voice and May Huang’s beautiful translation make the poems come more alive than ever in both languages. I remember talking to May for the first time as translators and hearing about how much time and effort she has put into making this poetry collection happen. Since our first conversation, I have been immensely inspired by her journey in translation and therefore embarked on my own project. Reading through this collection is like revisiting my many dialogues with May, learning that she has traveled to meet the author and has experienced the change of the city in her way, along with all the sentimentality we share as we go back and forth between the States, Hong Kong and Taiwan. It is that sense of familiarity with a particular place, like how she and the poet connect with Hong Kong and how I engage with my hometown in Taiwan. This sentimentality is not just about remembering the spoken, less represented languages (Cantonese, for example), but also how the change of landscapes affects the way we perceive the world(s) around us. This collection is for readers who are seeking a tender read teeming with life, nostalgia and remembering; it brings us to understand another cultural landscape and come back to reflect on our own.

Jenna Tang is a Taiwanese writer and translator who translates between Chinese, French, Spanish, and English. Her translations and essays have been published in Latin American Literature Today, AAWW, McSweeney’s, Catapult, and elsewhere. She translated Lin Yi-Han’s novel, Fang Si-Chi’s First Love Paradise, to be published by HarperVia in May 2024.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, February 13, 2024