Saving Lost Sounds: Translating Southern Pomo and Salt Pomo One Morpheme at a Time

Neil Alexander Walker interviewed by Peter Constantine

Part of the incredible patience of this group of people in this painstaking quest was the strong desire to reclaim as much of their lost language as was possible.

How do you translate a literary text from a recently extinct language with no dictionaries and minimal documentation? In this interview, I ask the linguist Neil Alexander Walker about his work with two extinct Pomoan languages of California, which includes translating texts and creating dictionaries and grammars. He shares insights from these processes as well as his translation workshops, where he has collaborated with tribe members to analyze elusive literary texts and help them reconnect with their heritage languages.

Peter Constantine: When I did a google search on the Southern Pomo language, I was surprised that Google’s AI Overview popped up, offering two striking bits of information concerning the year 2020. The first was that that was the year that Southern Pomo became extinct, and the second that it was the year your grammar of Southern Pomo was published.

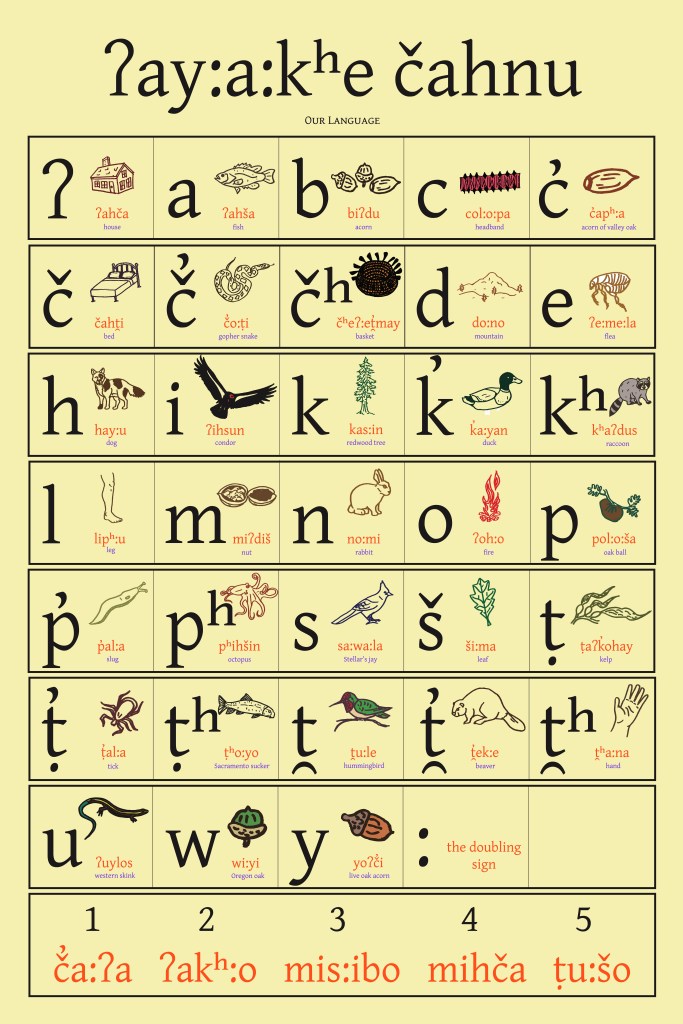

Neil Alexander Walker: Google’s AI is probably the last place you’d want to go to get any information on Southern Pomo, but the second of those facts at least is true. The last fluent speaker was Olive Fulwider. She learned the language as a child and spoke it with the few other remaining speakers throughout much of her adult life; her phonology and grammar were true to what is attested in recordings of speakers born in the late 1800s. Olive was my wife’s mam:ac̓, her father’s mother’s elder sister (in other words, my wife’s great aunt), and we got to visit with her several times before she passed away in 2014. That was when the last truly fluent speaker was lost.

PC: Some people remained who had knowledge of the language?

NAW: There was a second speaker of sorts, Tony Pete, whom I met once in about 2003 or 2004. He had native phonology and extensive knowledge of the language, but he’d only spoken it as a child and left home as a young man. I played a recording of an elder who was born in the late 1800s and had died around 1970, but Tony Pete could understand only the gist of what was being said. He was a member of a different tribe, and it was difficult to arrange meetings with him due to his advanced age and the concern of his loved ones. I think Tony Pete died in 2019 or 2020. He was born in 1919, one year after Olive Fulwider.

This brings me back to the fact from Google’s AI Overview you quoted that is true: in 2020, my book, A Grammar of Southern Pomo, was published by the University of Nebraska Press. The back cover includes the following text: “A Grammar of Southern Pomo is the first comprehensive description of the Southern Pomo language, which lost its last fluent speaker in 2014.” I can only assume that Google AI doesn’t have the back cover in its database!

PC: It’s fascinating, and sad, that there was only one fluent speaker left as you were working on the grammar. What was your first encounter with Southern Pomo? Were you already working on the language when you met Olive Fulwider for the first time?

NAW: My first encounter was in 2000, when my future wife invited me to her family reunion in Sonoma County, California. My wife is a member of the Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians (rancheria is the the word for reservation in California), for which Southern Pomo was the primary heritage language, though a minority of Tribal members have an unrelated language, Wappo, as their heritage language. I had a vague understanding that California Indigenous languages were endangered, and so, out of pure curiosity, I asked whether any of the family at the reunion spoke their language. At this point, neither Jenny nor her relatives knew that the scholarly name of the language was Southern Pomo. They talked about “speaking Pomo” or “speaking Indian.” But my wife’s relatives introduced me to her great-aunt Olive.

PC: That was the first time you heard Southern Pomo being spoken?

NAW: Yes. I asked Olive Fulwider the words for water and bear. So the first two words I learned were ʔahkʰa and bu:ṭaka. I left the reunion thinking how amazing it was that she knew this language, and with a strong desire to learn more about it.

PC: You once mentioned to me that you have taught Southern Pomo to English-speaking students through translation.

NAW: While I was preparing my grammar in 2019, I taught a graduate course in Southern Pomo at a summer institute held by the Linguistic Society of America at the University of California, Davis. My class was very much text-based, and I taught phonology and grammar by translating a single traditional narrative. So translation played a key role. Students were taught the building blocks of the language—its morphemes—and how to gloss them, in other words how to translate, analyze, and understand the meanings of each of these building blocks.

PC: So your translations were interlinear, as is sometimes done in Biblical translation, where words in the source text are linked one by one to translated words—literal, word-for-word translations?

NAW: The translation was interlinear and analytical—the students were linguists—but it was not a word-for-word translation. That wouldn’t have worked. Southern Pomo, like many indigenous languages of the Americas, and many other languages of the world, is agglutinating. This means that the various bits of meaning—the morphemes—in each word generally have a single function. That makes a morpheme-by-morpheme translation much more transparent and useful than it might be for many European languages. I then prepared a second, free translation of the text that moved toward a sense-by-sense translation, in other words, one that was not a dry morpheme-by-morpheme analysis of the text, and this I then used in class to give the flavor of the narrative in English.

PC: The idea of a morpheme-by-morpheme translation is fascinating.

NAW: If you take the English phrase “to their grandfather’s place,” a word for word translation into German, French, or Italian could be a useful first step in a translation or in a language student’s attempt at understanding the phrase, since the languages have similar structures. In Southern Pomo, however, “to their grandfather’s place” is the single word mač:ac’yačo:šan. In fact, since kinship distinctions are vital in Southern Pomo, the meaning of this word is also more specific than an English version would usually be. Mač:ac’yačo:šan means either “to their own maternal grandfather’s place” or, alternately, “to their maternal great uncle’s place.”

PC: How would you or your students approach a morpheme-by-morpheme translation of mač:ac’yačo:šan?

NAW: The word begins with maH-, a prefix that indicates the possessor of the kin term—in this case “his,” “her,” or “their own.” This prefix, however, is not a possessive pronoun: the Southern Pomo pronoun for “his,” her,” or “their” is the word ʔat̯:i:kʰe, which is totally unrelated to the unique kinship prefix maH-.

The second morpheme is the root -ča-, which can never stand alone. It means “mother’s father” or “mother’s father’s elder brothers,” depending on the context. This root must take the suffix -c’-, a generational suffix that indicates that the kinsman is older than the parents of the speaker. The alternative morpheme would be -ki-, used for kinship terms that refer to relatives who are younger than the parents of the person who is either uttering the term or to whom the term is being addressed. Thus, in English, were I to apply this morpheme, it could go only on “aunt” and “uncle” if they happen to be younger than the parent to whom they are a sibling, but it would always go on “brother,” “sister,” and “cousin” because they are a generation below my parents and assumed to be younger.

So, you can see how complex things can get and what challenges a translator of Southern Pomo into English would be facing.

PC: This intricate complexity strikes me as fascinating. A major challenge. I can definitely see why a first draft of a translation would need to be morpheme-by-morpheme if a translator is unpacking a text. What was the narrative that you translated?

NAW: We have under a dozen surviving traditional narratives in Southern Pomo. I wanted to make sure that the text I chose for my class could be used as an appendix in the grammar I was writing. When I used to teach Southern Pomo at the Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians, I chose a traditional story collected by the linguist Abraham M. Halpern from a native speaker, Annie Burke, in the early twentieth century. It is the tale of Rock Man and Gray Squirrel. I chose this story because it has only two participants, Rock Man and a clever squirrel. That made the story easier for students to follow, because Southern Pomo often omits overt subjects or objects and has no person-marking on the verb. It is also a very entertaining story.

PC: The Rock Man is a living being made of rock?

NAW: Yes, that’s right. Rock Man meets Gray Squirrel far away from any settlement. They decide to play a gambling game, where each exchanges his archer’s bow with the other. There is lots of fascinating vocabulary. Whichever of the two contestants is able to pull the other’s bowstring with enough force to break the bow wins the game. Gray Squirrel, the obviously weaker player, cheats by gnawing Rock Man’s bow, but Rock Man catches him in the act. A vital feature of the story is that Rock Man chases Gray Squirrel through the Northern Californian forests, and the translator encounters words for sugar pine, Douglas fir, and other features of the local landscape. Eventually, Gray Squirrel climbs a massive Douglas fir tree, one so huge that even the rock giant cannot topple it. Ultimately Gray Squirrel shoots Rock Man, who explodes, turning into the rocky coast of Sonoma County.

PC: I also find your work with Northeastern Pomo very interesting. Is that language related to Southern Pomo?

NAW: There are many Pomoan communities, and a total of seven mutually unintelligible Pomoan languages. Southern Pomo was the heritage language of more than one rancheria. Northeastern Pomo, which the Salt Pomo people of the Stonyford area in Northern California call Chhé’ee fókaa, could be called a sister language of Southern Pomo. They are from the same family, having split apart from a common ancestor at least a millennium ago. They might be as close as German and Swedish. The Northeastern Pomo had a very strong and independent position in Northern California, as they controlled the valuable salt deposits around Stonyford—hence the name Salt Pomo, or Salt People. They are the only Pomoan group native to the Sacramento River drainage and have a unique language that marks them as a “relictual” Pomoan community, in other words the descendants of an ancient culture that once inhabited that entire area.

PC: From what I understand, Northeastern Pomo lost its last speaker some fifty years ago and has very little documentation with which one can work in order to reconstruct the language?

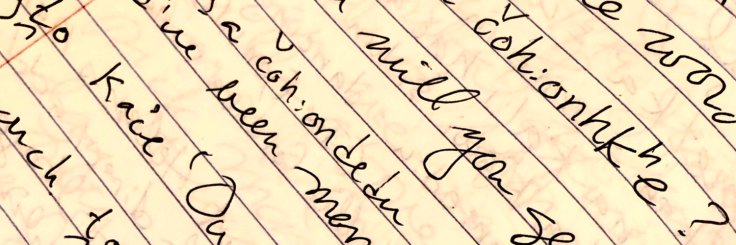

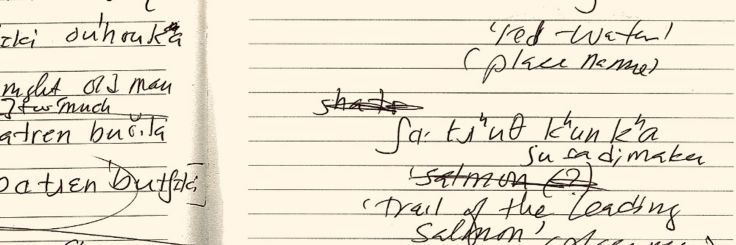

NAW: I am putting together a grammar of the language and completing a dictionary that will be some 250 pages long. The aim of this dictionary will be to contain every known word attested in writing that documented previous generations of fluent speakers. There are two significant texts with glosses in the language, gathered in 1940, again by Abraham Halpern, from the native speaker San Diego McDaniel. Halpern had in fact mistakenly recorded his name as Santiago, but in 2019, when the Chhé’ee Fókaa elders took me to his grave, they told me his true name was San Diego. If both of San Diego’s texts were typed up without any glossing in single-spaced format, they might fit into a dozen pages or less.

PC: I assume the glosses that Halpern created must have been an important key to understanding the inner workings of the language.

NAW: They have been, but they are extremely simple and rough glosses. They only offer a partial insight into the texts. Consequently, inference plays a central role when one sets out to translate these texts. To give you a simple example, if the Northeastern Pomo text were to say something like “My friends are here,” the translator might need to infer if the text means that the friends have arrived, or if the friends are being introduced, or if the friends are from here, moving away from here, moving toward here. And is it even many friends we’re talking about, or just one? Are they my friends or someone else’s? We might not even know if what is happening to these friends is happening now, or in the past, or is about to happen. The possibilities are almost endless. All this because the Northeastern Pomo text we have is missing a morphemic breakdown, in other words a detailed representation of the meaning and structure of the words that are glossed.

PC: The constraints involved in such a translation seem almost insurmountable.

NAW: It is a fascinating challenge though. It is slow and very absorbing work. In Pomoan tales, for instance, there are many animal characters, at times anthropomorphic, and San Diego McDaniel who provided this text to Abraham Halpern occasionally makes animal sounds. He will say “bear” and then growl. The inference that the translator has to make is whether the narrator has now become the bear, or if the bear simply growled. One has to check and double-check everything before one can confidently interpret the lines. I workshopped the texts with a group of Salt Pomo people for a year and a half, and of the 200 lines of the text, we only analyzed and translated about a hundred lines. As for myself, in my translations I average about five lines a week. And I’m talking intensive work, averaging one line per hour, and then also checking elements of vocabulary and morphological patterns in every single extant writing in Northeastern Pomo and also in related languages, to see if there are clues to elusive meanings that can confirm that my inference is accurate. It is somewhat like the task of the paleographer-translator trying to decipher the words of an ancient language. It is meticulous and hyper-careful work, because we are working with a language that was “discovered” very late by Western linguists, in 1902. It was the last Pomoan language to be identified, and the first to become extinct. In other words, a double challenge, as there was not enough time to document it in any significant way before it was no longer spoken.

PC: It is admirable that the group of Salt Pomo people you worked with had the patience for such a painstaking process of translation and analysis. It is hard to imagine that even the most dedicated graduate students of linguistics would be prepared to commit to such a project.

NAW: It was a very personal matter for the group in the workshop. They wanted to learn as much of the language as could be culled from the texts we had. Imagine an apocalyptic future where the English language is no longer spoken and almost all the literature ever created in the English language has perished. Imagine: no Shakespeare, no Milton, no Austen, Dickens, or Woolf. Just a single short story—that’s all that’s left of English—and a group of descendants of English speakers come together with a linguist like myself and use that one story to find out as much as they possibly can about their ancestral language. That quest to learn everything that could possibly be learned about their language energized the Salt Pomo people in the workshop. I’m not saying that everybody managed to keep up entirely, but there was that dedication, especially among the elders. I haven’t completed the translation of this 200-line story yet—it is something I am still planning to do. It is a very painstaking process, and there is always the underlying fear of ultimate failure, as there might simply not be enough information available.

PC: Did the group of Salt Pomo people you worked with know some of the language?

NAW: The elders knew a few words, in many cases only half-remembered, that they had heard their grandparents say. There were incredible moments when we would come upon a word or cultural concept in the text and one of the elders would remember something in connection to it. Our group would have continued our translation and language analysis meetings beyond the year and a half that we workshopped these texts, but my mounting teaching and research commitments on the other side of the world, in Australia, meant that we had to stop. But part of the incredible patience of this group of people in this painstaking quest was the strong desire to reclaim as much of their lost language as was possible. It is sad that there were limits to what we could reclaim, but every new word we discovered and identified was an extraordinarily important event. A cause for celebration.

Neil Alexander Walker holds a PhD in linguistics from the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is affiliated with James Cook University (Cairns, Australia) and serves as the Vice President for the Western Institute for Endangered Language Documentation. He is an expert on the Pomoan languages, an Indigenous Northern California language family. He has also conducted fieldwork on the Panim language of Papua New Guinea. He works with the Chhé’ee Fókaa Tribe of California to describe their language and is currently translating their longest extant traditional text with their collaboration.

Peter Constantine’s recent translations include works by Augustine, Rousseau, Machiavelli, and Tolstoy; he is a Guggenheim Fellow and was awarded the PEN Translation Prize for Six Early Stories by Thomas Mann, and the National Translation Award for The Undiscovered Chekhov. He is Professor of Translation Studies at the University of Connecticut and publisher of World Poetry Books. His novel The Purchased Bride was published by Deep Vellum in April 2023.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, April 22, 2025