Quotidian Violence: Review of The Book of Affects by Marília Arnaud, translated by Ilze Duarte

by Michelle Mirabella

Arnaud and The Book of Affects seem to push back on this ill-fitting, reductionist label of “regional literature.”

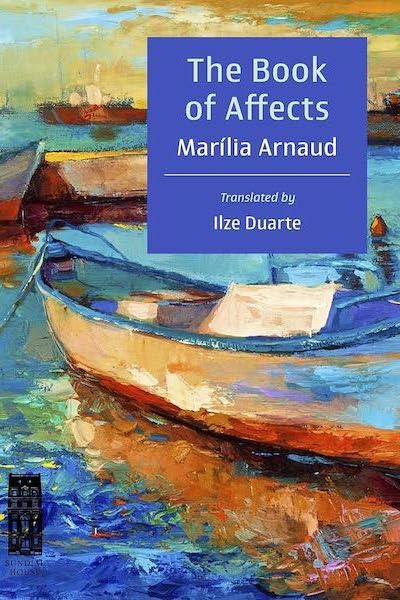

The Book of Affects by Marília Arnaud, translated from the Brazilian Portuguese by Ilze Duarte. Sundial House, 2024, 113 pp., $14.40. ISBN 979-8-9879264-6-8

What might a reader expect from a book of affects? A catalogue of emotions, a compilation of expressions and gestures, maybe even… a translation? The Book of Affects by Brazilian author Marília Arnaud is indeed a translation, by Ilze Duarte, but a straightforward catalogue of emotions it most certainly is not. Using dark, psychological realism the nine-story collection delves into the psyches of nine different protagonists and the relationship dynamics of their varied situations.

This collection, originally published in Portuguese back in 2005 by 7 letras, is but one of numerous works by this award-winning Brazilian author. Born in Campina Grande, in the northeastern state of Paraíba, and now living in its capital city João Pessoa, Arnaud has published four story collections, three novels, and a children’s book, and is featured widely in anthologies in Brazil. I share Arnaud’s hometown and current city because translator Ilze Duarte taught me something about place in Brazil in her piece on Marília Arnaud in the Columbia University Press blog:

To acknowledge a Brazilian writer’s place of origin is often meant… to celebrate the diversity of Brazilian culture and literature. There is a danger, however, in regarding literary works from various parts of Brazil as “regional literature” … synonymous with literature depicting the particularities—what was “typical”—of the various regions of Brazil and local communities. (2024, paras. 3-4)

Arnaud and The Book of Affects seem to push back on this ill-fitting, reductionist label of “regional literature.” Writing outside the major cities, in a “region” of Brazil, Arnaud seems to do the opposite of “depicting the particularities” of a place and instead dives into complexities of the human condition, transcending borders.

As for those complexities, The Book of Affects does explore the emotional aspect of the human condition, as might be expected from its title and how the work has been framed, but I would like to offer a more sinister overarching theme: the patriarchy and its violence. In fact, reflecting on this book had me rereading some bell hooks (2015) to refresh myself on the imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy, something bell hooks characterizes as a social disease, one that perpetuates the array of violences on display in these stories.

Arnaud, in this work, reflects the pervasive nature of violence in our world, depicting some violence as apparent while leaving much of it to lurk in the details. The femicides in “The Man Who Came From a Dream” and “Açucena,” for example, are overtly violent, but let’s take a look at some of Arnaud’s details. In “Thy Neighbor’s Wife,” the narrator is in love with (and sleeping with) his father’s wife. And when she asks the narrator to end things and leave, his first-person telling talks of his pain and despair, but there’s also: “I grabbed her arm roughly. She groaned but didn’t move. I had the urge to hurt her” (Arnaud, 2005/2024, p. 68). Violence. In “Not Even the Stars Are Forever” the first-person narrator is a child observing the adults around him as his mother wastes away in illness and the father neglects them. And through the eyes of this child, we see child abuse and domestic violence: “I have always wondered why Mom likes him so much…there must be a reason, otherwise she wouldn’t… lower her eyes or soften her voice when he is irritable. Let alone allow him to hit me for no reason. I think she is afraid like I am… Why does she put up with his threats …” (Arnaud, 2005/2024, pp. 94-95). Violence. In “Flesh and Agony” the narrator decides to tell her husband of her involvement long ago with another man, an experience she says she sought, but she also acknowledges the anguish and torment he caused her. What on the surface appears to be a confession of infidelity also exposes violence. She tells her husband of their first sexual encounter, their first encounter at all: “with each stab, his crazed eyes fixed on mine, he whispered ‘bitch,’ and that mantra started seeping through me…” (Arnaud, 2005/2024, pp. 8). Though violence is not always at the heart of these stories, it can be found in each and every one of them. What Arnaud has done is compile a book of stories depicting the complexity of relationships which show us that regardless of the dynamic at the fore, there is always something of violence lurking, inherent in life.

To carry this topic of violence over to a discussion of this work as a translation, it can also be said that violence is being done to the source text through the act of translation. Lawrence Venuti (1995) in The Translator’s Invisibility uses the term “violence” to describe translation and then goes on to talk about Friedrich Schleiermacher’s argument that there are only two methods of translation, a domesticating process and a foreignizing process, and how Schleiermacher’s choice is to foreignize; “this led the French translator and translation theorist Anoine Berman to treat Schleiermacher’s argument as an ethics of translation, concerned with making the translated text a place where a cultural other is manifested…” (p. 15), but other according to whom? Kavita Bhanot and Jeremy Tiang (2022) in their introduction to Violent Phenomena: 21 Essays on Translation problematize that dichotomous framework, calling attention to the fact that “it defines translation strategy in terms of difference from a presumed normality” (p. 14). If we accept Venuti’s argument that translation is violence, Ilze Duarte mitigates that violence by destabilizing a mainstream perspective on language, that “presumed normality,” beginning right with the title: The Book of Affects, a boldly literal and certainly purposeful choice. Afetos in the Portuguese is a tricky word to bring into English and encountering affects in the title is a choice that frames what is to come. Although Ilze makes use of both foreignizing and domesticating methods throughout the work, such as a domesticating “Mom” or a foreignizing “Belzinha,” beyond those surface-level choices, it is in the very sentences of Ilze’s prose where I see the Portuguese floating just beneath the surface, disrupting the English-language reader’s gaze on this text. There are lines as simple as “if I’d taken the bus, as you might have advised me to, I would’ve escaped the water but not this misery” (Arnaud, 2005/2024, p. 86) where the English grows thin enough to feel the pulse of the Portuguese beating within it, alive and well. My impression seems to be shared by author Amy Cippola Barnes (2024) who blurbs the book on its back cover saying:

Translator Ilze Duarte guides nine short stories from the original Portuguese to English with brushstrokes of both languages. Duarte’s translation becomes a conversation between two contemporary artists, both with their own individual ties to Brazil and unique voices.

Those brushstrokes of both languages refer to more than the occasional word but the whole of Duarte’s translation.

This story collection by Brazilian writer Marília Arnaud prominently features the violence of the imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy, and if translation is violence on the source text, Arnaud’s translator Ilze Duarte in this translation gives us a glimpse of what a more peaceful coexistence could be. The Book of Affects marks an English-language book-length debut for both author and translator, and as translator Ilze Duarte continues to work on translating Marília Arnaud’s oeuvre, I am certain that there will be more to come.

References

Arnaud, M. (2024). The Book of Affects. Translated by Ilze Duarte. Sundial House. (Original work published 2005)

Bhanot, K. & Tiang, J. (2022). Introduction. In K. Bhanot & J. Tiang (Eds.), Violent Phenomena: 21 Essays on Translation (pp. 9-20). Tilted Axis Press.

Duarte, I. (2024, August). Ilze Duarte on Marília Arnaud and The Book of Affects. Columbia University Press blog. https://cupblog.org/2024/08/20/ilze-duarte-on-marilia-arnaud-and-the-book-of-affects/

hooks, b. (2015). Feminism is for Everybody. Routledge.

Schleiermacher, F. (1992). “On the Different Methods of Translating” (W. Bartscht, Trans.). In R. Schulte and J. Biguenet (Eds.), Theories of Translation: An Anthology of Essays from Dryden to Derrida (pp. 36-54). The University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1813).

Venuti, L. (1995). The Translator’s Invisibility (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Michelle Mirabella is a Spanish-to-English literary translator. In addition to her translation of Catalina Infante’s debut novel, The Cracks We Bear (World Editions, 2025), her work appears in the anthologies Best Literary Translations (Deep Vellum, 2024) and Daughters of Latin America (HarperCollins, 2023), as well as in venues such as World Literature Today, Latin American Literature Today, and Southwest Review. Michelle holds an M.A. in Translation and Interpretation from the Middlebury Institute and is an alumna of the Banff International Literary Translation Centre and the Bread Loaf Translators’ Conference. Find more of her work at michellemirabella.com.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, August 26, 2025