Archival Relations and Activist Intimacies: from the GIP to Intolerable

A conversation between Perry Zurn and Erik Beranek

The time has come to put an end to the scandal of the prisons … All the reforms are worthwhile, but they don’t get at what is essential. It is really a question of breaking down prison walls, of destroying the carceral universe, which doesn’t mean, as they feign to believe, entering into a universe without sanctions overnight. To apply the law according to both its letter and its spirit, that, already, would empty our prisons by three-quarters…

—Jean-Marie Domenach, “To Have Done with Prisons”

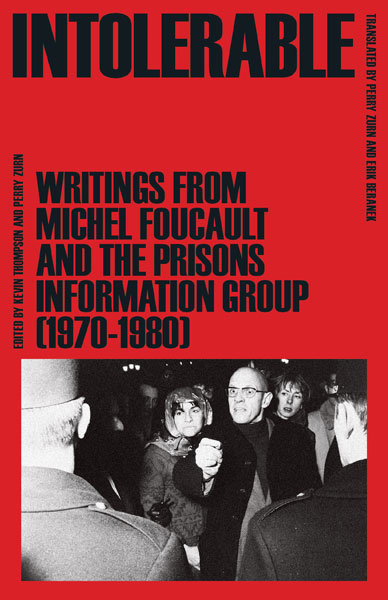

Intolerable: Writings from Michel Foucault and the Prisons Information Group (1970-1980) was published by University of Minnesota Press in August 2021. The volume, edited by Kevin Thompson and Perry Zurn, and translated by Perry Zurn and Erik Beranek, brings together a representative archive of the Prisons Information Group, a 1970’s French prison activist network in which prisoners (esp. Serge Livrozet) as well as academics (e.g., Michel Foucault, Hélène Cixous, and Gilles Deleuze) were involved. Perry and Erik conducted the following conversation in November 2021.

Erik Beranek: First off, I want to take this opportunity to thank you again, Perry, for inviting me to be a part of this project. There’s so much going on in this archive—lots to think about politically and philosophically, and lots of tricky challenges for us translators! Before turning to the GIP and to the book itself, though, I wonder if you might tell our readers about the genesis of this project? How did you first encounter the GIP and how did the idea to assemble and translate this volume come about?

Perry Zurn: It all started about ten years ago. I was still in graduate school at the time and Kevin Thompson asked me to come on board as a translator (and then co-editor) of the project. He had come across this incredible archive of prisoner-led resistance, with innovative theoretical reflections and activist strategies. It had clear relevance to contemporary prison activism, as well as political theory more generally. But it was also a rich record of resistance, allyship, coalition, belonging, courage, and hope. Although I was unaware of critical prison studies at the time, I bore a love of French and Foucault, and a commitment to issues of epistemic and social justice, so I immediately said yes. We started out thinking it might be a handful of pieces in Foucault Studies, or perhaps a special issue. But to really do it justice, and provide the kind of context, annotations, chronology, further reading resources, etc. that would really make the archive widely accessible (and useful), it needed to be a book. It’s at that point that we asked you to join the project. And we really couldn’t have done it without you. So perhaps I might ask, What made you say yes?

EB: A number of things drew me to the project. For one thing, the fact that both Foucault and Deleuze were involved in the GIP certainly piqued my interest. They’ve long been major influences on me, so having the opportunity to really dig into such a significant and creative event in their respective careers (just before Discipline and Punish for Foucault and right around the time when Deleuze and Guattari would be writing Anti-Oedipus) was quite exciting. That said, to focus too much on the many prominent intellectuals who took part in the group (Foucault, Deleuze, Cixous, Genet, etc.) is kind of to miss the point. One of the most interesting things about the GIP’s tactics was the way it broke with certain common forms of political activism and with the typical model of the engaged intellectual: instead of speaking on behalf of or representing the marginalized and oppressed, it sought ways to facilitate the political agency of those directly involved (first and foremost the prisoners, but also their families, the prison guards, prison psychiatrists, etc.), to communicate their knowledge and outrage, to allow the intolerable to pass through the walls that hid it. As a result, the archive is remarkably polyvocal, bringing together a number of different registers—and this linguistic and rhetorical diversity can’t be uncoupled from the tactical stakes. I found it all to be utterly compelling—and I knew it would be an exciting challenge for me as a translator.

You and Kevin go into the history and tactics of the GIP in great detail in your introduction, but would you mind giving a bit of an overview here for our readers? How did their tactics differ from those of other activist groups of the time (or perhaps even now)? What did this (as I’ve just decided to call it) “polyvocal” approach allow them to accomplish?

PZ: Working in the aftermath of May 1968, the GIP’s militancy was brief but clear-eyed. Active from late 1970 to early 1973, it took the French public by storm, insisting that prisons be no longer left in peace. Why? Because prisons are, in the GIP’s own words, “intolerable.” While the GIP’s primary line of attack was prison resistance and prison abolition, its successor group the Comité d’Action des Prisonniers (CAP), led by formally incarcerated Serge Livrozet among others, expanded its work and played a not insignificant role in abolishing the death penalty in France in 1981.

A cornerstone of the GIP project was to serve as a “relay” between people in and outside the prison. Their goal, as they repeatedly said, was “to give the floor [donner la parole]” to prisoners. Working with currently incarcerated people, as well as their families, friends, doctors, lawyers, social workers, etc., the GIP signal boosted the scathing assessment of prison from those with an intimate knowledge of it. This took a variety of forms, from smuggling prisoner questionnaires and publishing dossiers of prisoners’ writings, to covering prison riots and publicizing prisoners’ demands. As such, the GIP archive is a bit of an unruly beast, replete with public announcements, flyers, manifestos, reports, pamphlets, interventions, press conference statements, interviews, letters, round table discussions, and even a play, in addition to more formal essays. The plurality of voices, or the polyvocal approach as you put it, makes this archive a particularly difficult one to edit and even more challenging to translate. Could you talk about some of those challenges, perhaps?

EB: There are two challenges that come to mind right away. On the one hand, across all the texts (regardless of the form the text took or the register the author wrote in), there was a general challenge of contextual vocabulary. Acronyms of activist groups and legal institutions, legal and prison terms (e.g., the prétoire or the “travel ban” [interdiction de séjour], slang—there was a lot to hold onto and I always had a lot of lists going. I suppose that really isn’t so different from what translators are always having to do: you always need to keep track of terms and try to remain consistent where it seems necessary to do so. But in this case, there were a lot of terms from a specific political, institutional, and lived regime of experience that I, at least, was mostly unfamiliar with coming into the project—which meant that I had a lot to learn in the process.

On the other hand, we’ve already said that the texts making up the archive take many different forms (pamphlets, questionnaires, essays, etc.) and are written in a variety of registers: some are by academic intellectuals and activists with training and education to spare, while others are by self-taught writers, by (then) currently and formerly incarcerated people, by people who may have had little access to education, people who were writing out of necessity, who needed to make or maintain a connection with the outside. Strange though this may be, given my training (and the realities of my everyday linguistic experience), I am probably more likely to get tripped up by everyday, colloquial French than by a book by Foucault. And of the more colloquial, unpolished texts in Intolerable, the “Letters from H. M.” were (for me) definitely the most challenging.

It wasn’t just that the letters were rough around the edges that made them difficult to translate, though. There’s a real intensity of experience that seems to be constantly overflowing in them. H. M. was the pseudonym used for Gérard Grandmontagne, when a selection of his letters were made the centerpiece of Intolerable 4: Prison Suicides from 1972. Grandmontagne was in and out of detention centers for years, mostly for petty crimes and drug possession, and was ultimately imprisoned after being tricked into procuring drugs for a plainclothes cop. In 1972, he was confined to solitary confinement for being a homosexual, and he hanged himself there using electrical wires he pulled from the ceiling.

The letters were written in the last days of Grandmontagne’s life and bear witness to his desperate attempts to grapple with the situation he finds himself in, to maintain intellectual and emotional connections to the outside, and to comprehend the set-up that led to his imprisonment and the devastating cycle that is being forced upon him. They are full of affection and remarkably astute observations, as well as unfinished thoughts, bouts of depression and frustration, and ideas that begin to drift off as the powerful sedative he is forced to take begins to take hold. Many of the letters end in a meandering drift as he struggles against the drug’s inevitable effects. There is so much packed into these letters—so much raw honesty, so much desire, so much struggle—that translating them was an extremely daunting task. It’s a very direct voice that embodies the havoc wrought by the intolerable system that this archive is all about. And it’s certainly one of the pieces I found most rewarding to work on.

But I’d love to hear your thoughts on the challenges this archive posed, too, Perry. Are there any challenges that you remember running up against that I haven’t mentioned here or pieces that posed particular problems for you? And did any one piece end up sort of standing at the center of the collection for you? Any favorites, whether as rewarding translation experiences or as especially relevant for your own thinking, writing, and acting?

PZ: One of the biggest challenges for me was grappling with the skew of the archive itself. The GIP worked primarily with men’s prisons and its founding intellectuals were all men. This is certainly not the only skew of the archive, but it is one of the most profound. As we worked on culling, editing, translating, and annotating, this was among the concerns foremost in my mind. How to acknowledge, and in some cases even highlight, the crucial role of women in the GIP? In an archive about voice, it was hard not to notice the falling-silent of these voices. I started seeing them everywhere: protesting, intervening, collaborating, editing, researching, and creating. It was Catherine von Bülow, Hélène Châtelain, Fanny Deleuze, Josette d’Escrivan, Claude Liscia, Michèle Manceaux, Christine Martineau, Marianne Merleau-Ponty, Ariane Mnouchkine, Danièle Rancière, Édith Rose ….

And most of all Hélène Cixous. She was splattered across the archive, but she’d said very little about it on record. I got the brazen idea to ask for an interview. She was game from the start, but it took years to coordinate. Summer after summer slipped through our fingers as I took three different positions (the junior academic rigamarole) and she threw herself into her writing and her work with Théâtre du Soleil. She is nothing if not devoted. Then, one spring, I happened to be in Paris for a week and sent her a hail-mary missive. She replied within an hour and said, “Call me.” I found a quiet street corner in the 3rd arrondissement and rang. She gave me her address on the Left Bank and we planned to meet in two days.

It’s hard (impossible?) to convey the knee-buckling experience of meeting someone of Cixous’ stature, in the flesh, in her home—a figure I’d known since awakening to the world of letters and feminism. She was regal. Her eyes bore through me. She was honest and patient, pausing to listen to the roar of history and the whisper of syntax before answering. She spoke of the GIP gathering in her apartment, precisely where we sat. She spoke of working with Foucault, Deleuze, Livrozet, and the rest. She spoke of her unmatched love for Mnouchkine, whom she had just met at the time. The raw urgency of the moment was palpable. For her, everything about the GIP was connected to everything she cared about politically—issues of racism, misogyny, climate change, and social injustices of all kinds. But more basally, for her, the GIP was driven by the sort of hope that subtends all efforts to right and to write the world. “Hope is the blood of it,” she said—quickly, powerfully.

As I think back to the interview, which now closes Intolerable, I see it as a long reflection on the poetics of relation, of finding connection, of ephemeral links cast into the world and the moments some of them sometimes find home. There’s something elemental here. Something at the heart of the GIP which is always also much bigger. How might we be with one another? How might we navigate the violent rupture of human and non-human connection that marks the prison—and also, in not unrelated ways, the university? And how might we imagine something else, some other forest, in its place? That same week, I interviewed Nicolas Drolc, GIP documentarian. With a similar compulsion, he described the friendship between Livrozet and Foucault, and between Livrozet and himself. It was as if what is more fundamental than any activist network or initiative is the fragile intimacies they build and, through them, another kind of freedom.

In that light, perhaps we might discuss some of the contemporary resonances—even injunctions and invitations—of the GIP archive. How could this archive be more than fodder for intellectual curiosity? In many ways, it is a vibrant dossier of ways of being together in an unequal world—and working to change it.

EB: I really love what you’re saying here about the relations, connections, and fragile intimacies subtending much of the GIP’s work. And I’m inclined to answer your question by thinking along similar lines. One thing that strikes me as being exceptionally useful about the archive is the way it makes a certain time and place, and a collective action that took shape in that time and place, present—though present only in its irreducible variety, as a multiplicity. It is undoubtedly the case that many people will find their way to this book out of intellectual curiosity or on the basis of intellectual (possibly academic) pursuits, and that a number of those people will probably get to it by way of an interest in Foucault. But it’s interesting to think about the fact that, while, on the one hand, it’s impossible not to see Discipline and Punish emerging, at least in part, from Foucault’s work with the GIP, on the other hand, it would be horribly wrong to imagine that his work with the GIP was undertaken as some sort of research or means to an end. And yet, there might still be a way to think of the GIP’s work as being a sort of engaged empiricism. Thinking about the ways in which the thinkers involved in the GIP were leaving the walls of the university and seeking ways to involve prisoners’ families in the raising of questions, seeking ways to mobilize neighborhoods and to “give the floor to” prisoners themselves—thinking about all of that as an essential dimension of their “intellectual” work, which we should try not to lose sight of when studying them, seems incredibly important to me.

I should also say that some of my favorite pieces in Intolerable are the prefaces Foucault wrote to books by Serge Livrozet and Bruce Jackson. Not only are those books themselves incredible (as are Foucault’s reflections on them), but their inclusion is a reminder that the act of prefacing a book, the acts of publishing, republishing, compiling an archive, or translating might also be seen as acts of amplifying voices [donner la parole]. I don’t mean to suggest that prefacing or translating a book is in any way equal to the very direct forms of activism, witnessing, and alliance that we find in the archive (for instance, the incredible report by Dr. Édith Rose, a psychiatrist at Toul Prison). Still, finding precedents to a struggle or actions undertaken elsewhere and renewing or altering their actuality through translation and dissemination is something that can resonate with other kinds of work and help to generate novel connections. (We might think here of Intolerable 3, which focuses on the death of George Jackson and suggests connections between the GIP and the Black Panthers.)

I guess what I’m trying to say is that between the more direct (more explicitly activist) work that the GIP accomplished, and then the adjacent work of writing, translating, compiling, publishing, disseminating, etc., the archive brings together myriad manners of amplifying voices, of bringing into existence, and of engaging alongside others. (Honestly, I shouldn’t even say that something like publishing is in any way adjacent to the GIP’s “more activist” activities. The issue of smuggling prisoners’ voices out from behind the walls was of central importance to their work and publishing the Intolerable pamphlets was a major part of that. But I’ll leave it at that for now…) I find the archive exciting not just as an incitement to act, but also as an illustration of the ways in which a number of seemingly heterogeneous acts can resonate with one another to create something vast and open and brimming with interrelations.

PZ: Exactly! And all those effective relations and interrelations mean that while the GIP itself presented a largely unified front, it was full of internal tensions, just as the text/archive is always straining against its own confines (and translations). As you can see from the GIP’s compiled Lists of Demands, different “groupuscules” in different cities (and different prisons) developed unique and sometimes competing initiatives (e.g., the right to self-organize, to work, to medical care, to sexual and familial intimacy, to education, to newspapers and radio, to exercise, and the right to an end of the criminal record, solitary confinement, censored letters, beatings, arbitrary judgments, and the easily-abused points systems for good/bad behavior). And the very wealth of theoretical frameworks at the time (e.g., Marxism/Maoism, existentialism, poststructuralism, the anti-psychiatry movement), not to mention prisoners’ raw pragmatic urgency and their appeals to human rights, produced variegated self-conceptualizations of the GIP’s mission, its work, and its relation to the prison.

Perhaps the most profound complexity in the GIP archive surfaces around questions of prison reform. At some moments, GIP members swore to its supremely minimalist goals: simply to move information from the inside to the outside or, slightly more ambitiously, to serve as a circulation hub between them. At other moments, they agitated for (and in some cases won) certain basic prison reforms; e.g., right to a radio, and to Christmas packages. At still other moments, it is possible to see the invocation of prison abolition. Take scholar-activist Jean-Marie Domenach, for example. In his essay, “To Have Done with Prisons,” he describes the prison as a universe: “a universe without law,” “a universe without progress,” “a universe without hope.” And he says it’s time to be done with it. He calls on readers to break down prison walls (physically and ideologically), to rupture the forces of isolation that render bodies, thoughts, relations, and possibilities null and void.

The evocations here are stunning. What even is a universe? A pattern of light and heat, life and decay, relations of force and resistance. Explosive residue. And what does it mean to have done with a universe? How is a universe broken—broken down, broken into, broken open? What cosmic exigencies and collisions does such an image—indeed, such a vision—summon? What affects must grow cold? What enlightenment logics must be extinguished? What relations become obsolete? And what senses of failure must relentlessly be embraced (or, conversely, resisted)? For those today who might be reaching for legacies of prison abolition, and radical imagination, they have an unlooked-for resource in the GIP. Intolerable serves as an introduction both to the prison universe and to its cracks.

EB: This has been great, Perry. The project was so long in the making, it’s really nice to sit back and reflect on it for a moment. And, as always, it’s been a pleasure collaborating with you. I hope we’ve managed at least to offer a glimpse into the vast store of potential energy contained in Intolerable. Any final thoughts you’d like to convey to those people who will be coming to the archive for the first time, seeking points of resonance with their own work and lending it renewed actuality through the actuality of their own contemporary concerns?

PZ: Working together has been an absolute pleasure, Erik. Thanks for everything you’ve made possible in this book and beyond.

As for a final word, how’s this: Intolerable arrived on the scene fifty years after the GIP’s founding. Nonetheless, it’s hard to imagine anything more prescient, not only for prison activism and theory today but also for the perennial quest to learn how to be with—and through—one another, differently.

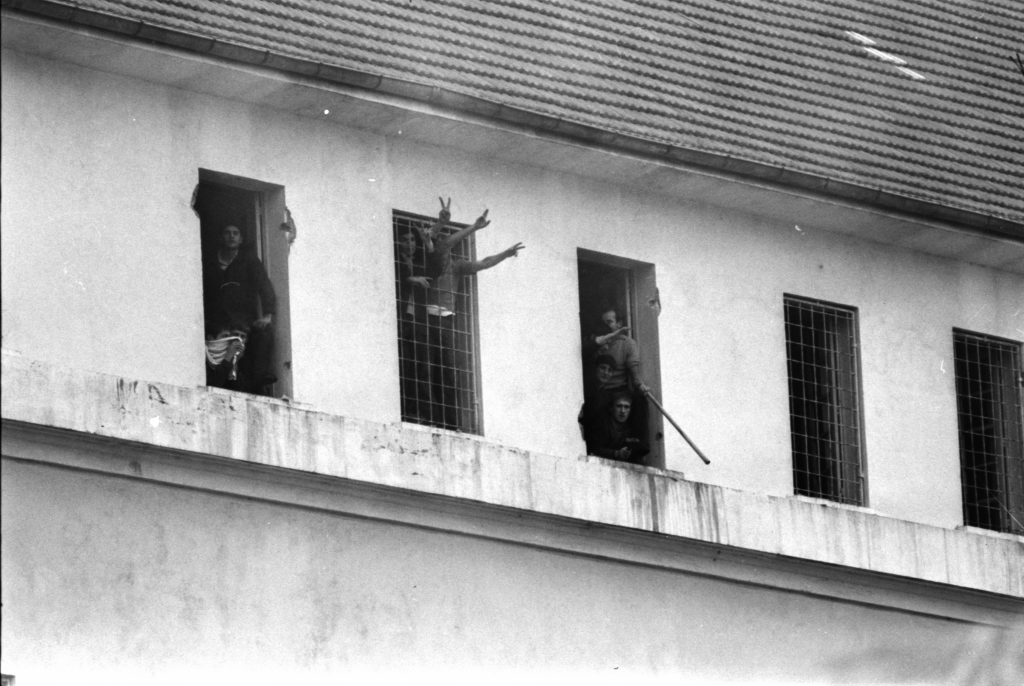

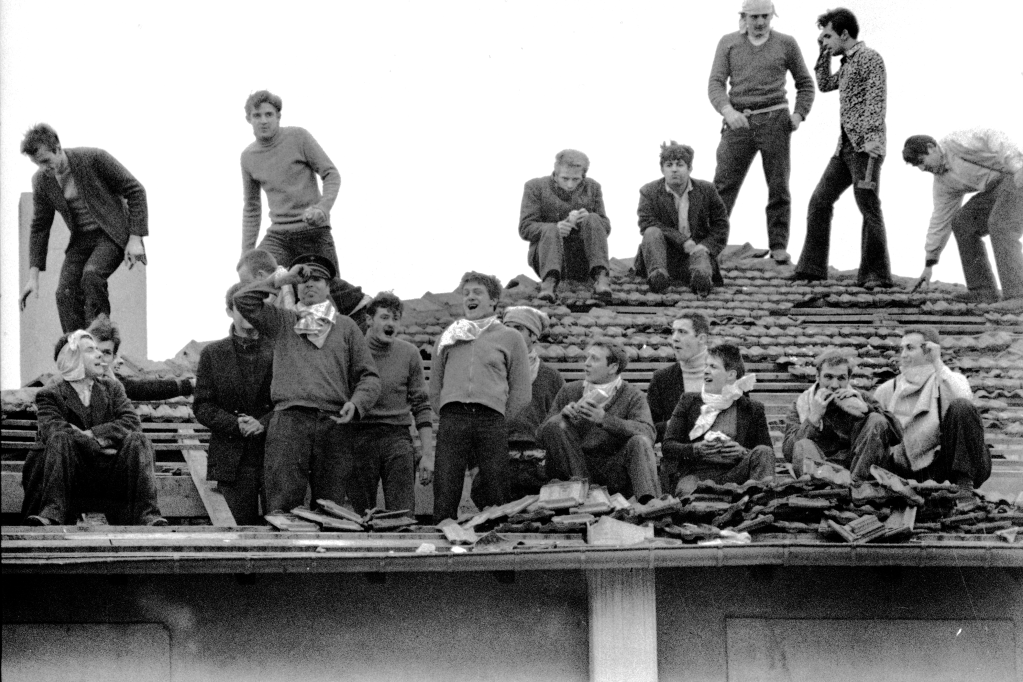

Photographs of Toul and Nancy Revolts, 1971-1972,

by Gerald Drolc, courtesy of Nicolas Drolc.

Perry Zurn is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at American University. He researches in political theory, ethics, feminism and trans studies. He is the author of Curiosity and Power (2021), and the co-editor of Intolerable: Writings from Michel Foucault and the Prisons Information Group (2021), Curiosity Studies (2020), and Active Intolerance: Michel Foucault, The Prisons Information Group, and the Future of Abolition (2016).

Erik Beranek is a writer and translator based in Philadelphia. He has translated works by Jacques Rancière, Étienne Souriau, Michel Foucault, and David Lapoujade. He works at the University of Pennsylvania Press.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, December 21, 2021