On the Origins of the Authors Guild Translation Model Contract

An Interview With Alex Zucker

I’d like to see more translators think of themselves as workers—again, as people who do a job to earn money—and of their work as labor, not only as art.

Hopscotch Translation: In April of last year, the Authors Guild published its first ever “Literary Translation Model Contract and Commentary.” Why is that important and how did it happen?

Alex Zucker: It’s important because 1) it marks the first time in the United States that a model contract for literary translation has been issued by an organization that advocates for translators as workers, i.e., as people who do a job to earn money (as the AG website says, “we fight for a living wage”); and 2) it comes from an organization that can support translators in their use of the contract because it has lawyers on staff who provide contract review to Guild members.

Previously the Translation Committee of PEN America (formerly known as the PEN American Center) promulgated a model contract for literary translation, first issued in 1981, and it played a critical role in advancing awareness of contractual terms among literary translators and publishers in the United States. But because PEN’s mission is centered on free expression for writers rather than the profession as such, the organization does not have staff devoted to contractual issues, and support for translators with questions or concerns about contracts came from unpaid members of the Translation Committee, whose ability—and availability—to respond varied greatly depending on circumstances. Nor is this service provided by either of the two U.S. organizations created with translators in mind, the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) (“dedicated to supporting the work of literary translators and advancing the art of literary translation”), and the American Translators Association (ATA) (“established to advance the translation and interpreting professions and foster the professional development of its members.”). So while authors in the United States have been able to avail themselves of the Authors Guild Model Trade Book Contract, with contract review provided to AG members by AG lawyers, translators in the United States had lacked this support until now.

A pair of provisos, lest anyone accuse me of withholding the full story: 1) In fact the Authors Guild has always been open to translators, and even before it published its model contract for literary translation it was providing contract review to its translator members, but until a few years ago this was not widely publicized, and most translators, including myself, were unaware they could join the Guild or that it offered contract review. 2) The Translators Association, a group within the United Kingdom’s Society of Authors, publishes a “Guide to Translator/Publisher Contracts,” similar in function to a model contract and commentary, as well as providing contract vetting to members (though not by lawyers), and is open to translators in the United States as well. Yet, whatever the reasons may be, historically, few U.S. translators have joined the TA, meaning that its contracts guide and vetting service have not been used by significant numbers of U.S. translators and therefore they have not had a substantial impact on the discussion or reality of working conditions for translators in the United States.

HT: Wow. That was a lot of information. I might want to come back to some of that at some point, but for now, maybe you can just tell me how it finally came about that the Authors Guild put out a model contract for translators?

AZ: This is also kind of a long story, though I think worth telling, because it illustrates the importance of taking the long view when it comes to creating meaningful change.

HT: I think you said it took something like five years to make the contract a reality?

AZ: Six, actually, believe it or not. Or seven. Depends how you count. I first approached the Guild about creating a translators section in December 2014, shortly after Mary Rasenberger came on board as their new executive director. She was open to the idea, but since she was new she asked if I could get back to her a few months later, after she was settled into her new position, and said in the meantime it would be helpful for more translators to demonstrate their interest by becoming members of the Guild and identifying themselves as translators when they joined.

This was during the time I served as cochair of the Translation Committee at PEN America (with Margaret Carson, in 2014–15, then with Allison Markin Powell, in 2016), which really was my initiation into the intricacies of publishing contracts. I want to emphasize that, because I think—in fact I know, because people have said so—that people assumed I was advocating on contracts because I was so knowledgeable about them, but in a way it was exactly the opposite: I worked as a translator for nine years before I translated a novel, and between my second and third novels another nine years passed. I didn’t belong to any translator organizations during those two decades, which meant I knew nothing about contracts, so my main concern when reviewing one was when was the book due and how much would I be paid. That was about it. I didn’t know squat about copyright or reversion of rights, not to mention royalties or subsidiary rights, and I was clueless how much anyone else was being paid, so there was no way for me to know if the fees I was being offered were similar to what other translators were paid. It was only after I won the National Translation Award from ALTA, in 2010, and then went to the ALTA conference to receive the award, that I became part of the “translator community,” met other translators, and began to attend translation-related events in New York. Which eventually brought me to the Translation Committee at PEN, where there was discussion of contracts, translator visibility, and so on. So I didn’t become cochair of the Translation Committee at PEN due to my vast knowledge or experience, but because I couldn’t stand just complaining about how translators were viewed and treated, and wanted to actually do something about it, and to help organize others to do so as well.

But to come back to the Authors Guild: Over the course of 2015, I began corresponding with Guild staff about issues of concern to translators that the Guild might be of help with, while encouraging translators to join the Guild so they could get legal advice on contracts. Seeking to get the word out about the Guild to as many translators as possible, I also began talking about it to Erica Mena, then executive director of ALTA, and she invited the Guild to send someone for the first time to attend the annual ALTA conference and offered them a table for translators to sign up as members. That didn’t happen that year, but Erica did make an agreement with the AG allowing ALTA members to join the Guild at a discounted rate, and by September 2015, thanks to the number of translators who joined the Guild in response to the coordinated appeal from ALTA, the PEN Translation Committee, and individual translators putting the word out through their blogs and social media, the Guild committed to moving ahead with a translators section and had become willing to consider my request that they run a survey on translator income and working conditions for translators in the United States.

HT: Wait a second! We were talking about the model contract. Now you’re talking about a survey of working conditions.

AZ: Right. Well, they’re connected, you see, because one of the things about being cochair of the Translation Committee was that translators would approach me—email me out of the blue, or message me on Facebook, or come up to me at an event—to share their complaints about publishers. Often about pay, but not only that, and as Margaret Carson and I moved into our second year as cochairs of the Translation Committee, devoting increasing amounts of time to advocacy on this front and hearing more and more grievances, I found myself wishing we had more systematic information—in other words, data—about the contractual terms that literary translators were being offered, and whether or not they were getting better or worse over time. My idea of conducting a survey of working conditions for U.S. literary translators was inspired by the 2008 CEATL survey of working conditions for translators in Europe, which I learned about thanks to Katie Silver, who used the survey as the starting point for a panel she moderated at the 2014 ALTA conference in Milwaukee, “Professional Literary Translators: Do They Exist and Can They Pay the Bills?” (The panel participants were Jessica Cohen, Ezra Fitz, Edward Gauvin, Anna Rosenwong, and myself, and the answers we ended up giving to the questions posed in the panel title were “yes” and “no.”) So my correspondence with the Authors Guild about what they could do for translators was focused on 1) creating a translators section within the Guild; but also 2) creating a model contract for translation; and 3) conducting a survey of working conditions.

Meanwhile, as the Guild was deepening its commitment to grow its advocacy for translators, in mid-2015 they said they were going to look at the PEN Translation Committee’s model contract—which, again, was the only existing one—as a possible starting point. I explained that the TC’s model contract had been of immense help to translators, but given that contractual matters were not part of PEN’s mission there was no one on the PEN staff devoted to keeping it up to date, or reviewing translator contracts, or answering translators’ questions on contractual matters, or providing ongoing education on contracts, and since these were all services the Authors Guild was already providing to its members, it would be best if the Guild could produce a model contract for literary translation of its own, which it could then use as the basis for vetting contracts for translator members. In January 2016, Michael Gross, the AG’s staff attorney, drew up and sent me a first draft model contract for translation. I passed it along for comment to a handful of translators who had been active in discussions of translator contracts and had expressed interest in helping to move the project forward: Katie Silver, Marian Schwartz, Jessica Cohen, Sandra Smith, and Allison Markin Powell. Based on their input, as well as on conversations we’d been having in the PEN Translation Committee over the previous two years while Margaret Carson and I were cochairs, in February 2016 I sent Michael back suggestions for revisions.

2016 saw a lot of turnover in the AG, so there was a pause in work on the model contract for several months, and through the remainder of the year, translation-related work at the Guild focused on the survey of working conditions. In April Jessica Cohen volunteered to work with me on the survey, and in May we drew up a first version, based in part on the AG’s own member survey of authors, in 2015, and in part on the survey the ATA conducts of its members every year.

HT: OK, so it’s 2016, a year-plus since you first made contact with the Authors Guild. They’ve agreed to set up a translators section but they haven’t done it yet?

AZ: Correct.

HT: And they’re starting to think about creating their first model contract for literary translation?

AZ: Yes. Which me and a few other translators have created a first draft of.

HT: And now you and Jessica Cohen start working with them on a survey of working conditions, to find out what sorts of contracts literary translators in the U.S. are actually getting at that point?

AZ: That’s right.

HT: OK. Just wanted to get that clear!

AZ: It’s kind of complicated, I know. In real time, it actually moved very slowly, since everyone involved was also working on other stuff, and of course all of us translators were doing this as volunteers, none of us was being paid for this work, so we just fit it in when we could. I want to emphasize that besides my correspondence with AG staff, I was talking about it regularly with—first, since they were my cochairs on the Translation Committee—Margaret Carson and Allison Markin Powell, then also Katie Silver, Jessica Cohen, Marian Schwartz, plus emailing with Sandra Smith, Susan Bernofsky, Esther Allen, Anne Milano Appel, as well as the UK translators Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Danny Hahn, and Ros Schwartz, who all have a history of tireless advocacy on behalf of translators and possess a wealth of knowledge about contracts and the publishing business in general. Honestly, I would give credit to every translator I spoke to in the years leading up to the Guild’s publication of its model contract, since they all had an influence on my thinking about it. The people I name here, though, are, again, the ones I turned to most often for feedback, input, guidance, and encouragement.

HT: Great. So, in 2016 . . .

AZ: In 2016, most of the Guild’s translation-related work was dedicated to designing the survey of working conditions. Jessica Cohen and I wrote the survey with Ryan Fox, then AG’s policy and advocacy director, which included figuring out not only which questions to ask and how to word them, but also how to reach as many translators in the United States as possible, as well as any translators outside the United States who worked with U.S. publishers. In the end, the survey was conducted in early 2017, with the results published in December.

HT: And this was a key lead-up to the model contract?

AZ: Well, yes, because after years of nothing but anecdotal information—translators sharing about their contracts and publishing experiences with one another on an individual basis—the survey showed the range of contractual terms translators were getting in this country, which could then help to determine which areas were most in need of improvement and where translators needed the most support and education.

A couple summaries of the survey appeared in addition to our own, including an excellent roundup on the site of Publishing Perspectives, and this one on Translationista, Susan Bernofsky’s blog. As Susan wrote:

The results are in part quite surprising. For one thing, far more translators receive royalties for their work than word-of-mouth might lead one to believe – a discovery that will no doubt be helpful to translators who’ve been refused royalties or even copyright in their work on the grounds that it (supposedly) isn’t usual for publishers to grant these things in translation contracts. Lo, but it is. Another welcome surprise: there seems to be very little differential in translator pay based on gender. That’s good to know, especially as nearly 60% of literary translators identify as female. Not so surprising (but it’s always good to see the hard facts & figures) is how white the field is: 83% of translators self-identify as white, with shockingly tiny percentages of African American, Asian American, and Native American colleagues (1.5%, 1.5%, and 1% respectively), and only 6.5% Hispanic or Latinx translators.

Unsurprising, on the other hand, was the low percentage of translators who reported being able to earn a living from their work and the lack of increase in pay in the five years leading up to the survey. (Detailed summary of the survey’s findings here.)

The other main development in 2017 was on front no. 1, creating a translators section or group within the Guild. In October the Guild hosted a meeting at its office in New York with Lissie Jaquette, who had been hired as executive director of ALTA in 2017; Mary Ann Newman and Tess Lewis, then cochairs of the PEN Translation Committee; plus Allison Markin Powell and Sandra Smith of the PEN TC and myself. As a result of that meeting, Mary Rasenberger and Sandy Long, the AG’s executive director and chief operating officer, decided to go ahead with the plan, and we agreed to call it the “Translators Group” (rather than section). One other outcome from that meeting was that in 2018 the Guild again offered a 20 percent discount on membership to members of ALTA, and in January 2018 Julia Sanches volunteered to be the first head of the Translators Group.

HT: So a lot of moving parts, gears grinding away in unison.

AZ: Yeah, “grinding away” is right. Once Julia came on board, she also began working with me and Jessica on getting the model contract finished, but it still took three years from that point to arrive at a final version and release it into the world, which finally happened in April 2021.

HT: May I ask why it took so long?

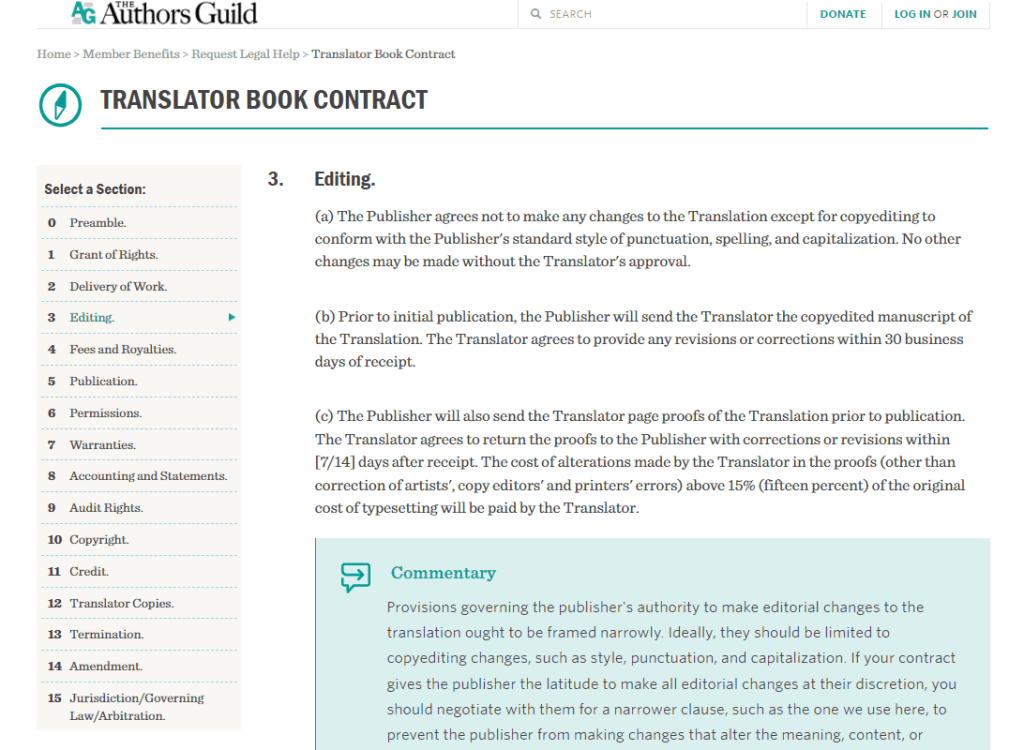

AZ: Well, it was partly because of staff changes at the Guild—in June 2018, Umair Kazi, who joined the AG in 2017, began working on it with us instead of Michael Gross—and partly because we kept discovering important aspects that we had neglected to include, or that were there in the contract but we hadn’t sufficiently addressed them in the commentary. This is key, actually: That what we published is not just a contract but a contract with commentary. Having a model contract in hand when you’re negotiating doesn’t do you any good if you don’t understand the terms, if you don’t know what your options are when it comes to certain terms, et cetera. When you negotiate with a publisher, it’s best to be able to know not only what to ask for but why it matters. So while a commentary is no replacement for input from a lawyer or someone else with expertise, it’s worlds better than having just a bare-bones model contract, with no explanations attached. Then at one point we paused because the Guild was bringing out a new update to its Model Trade Book Contract, and that was a priority. So yeah, various things at various times. And again, like I said, the three of us—Jessica, Julia, and I—were all doing this in between trying to earn our livings and all three of us were freelancers for most of these years, so there’s only so much time a person can devote to unpaid work. I feel like I need to say that, for people to understand that making change requires a commitment to plugging away, over the long term, and sticking with it, even—or especially—when it’s a slog and it feels like it’s bogged down or the project or campaign will never end, never come to fruition. This is something I’ve learned especially from political organizers. And for that matter, it was also a political organizer, Mariame Kaba, who inspired me to tell this story, because of her repeated appeals for organizers to document their work, so that those who come after will know what’s already been done, what’s been tried and has failed, or tried and has succeeded, so that not every new generation has to start again from scratch.

HT: So what’s next, what’s the way forward? Also, do you have any regrets about your work with the Authors Guild up to this point? Is there anything you wish you had done differently up to now, or would do differently if you could do it over again?

AZ: Those are all good questions. I wouldn’t say I have any regrets, exactly. I will say that I wish we would’ve done more disaggregation of the results from the survey of working conditions. For example, it would be useful to know to what extent working conditions vary based on language. Do translators from French, for example, which has historically dominated literary translation in English, on average earn more than translators of other languages? Less? Or do they show the same variation? We have that information in the responses, obviously, but at the time we published the results, the Guild couldn’t spare anyone to do that analysis, and we weren’t organized enough to find someone who could do it for free—or to fundraise quickly enough to pay someone to do it. But that’s OK. We did the survey in 2017 with the intention of repeating it in 2022 and continuing to do so at five-year intervals, so assuming we go ahead with that, I’ll definitely push for our findings this time around to include a disaggregation by language.

As for the model contract, I am extremely pleased with the outcome. I’m proud, even, of the work we did on it. Umair Kazi is a gem! He stuck with us through thick and thin (and probably eighteen drafts), and always did so with the utmost grace. And I can’t speak highly, or warmly, enough of Jessica Cohen and Julia Sanches. The three of us really worked as a team, someone always stepping forward when the others had to step back, and nobody ever threw up their hands and said, “Fuck it! I’m done. This is taking too damn long. I’m out.” The model contract was probably the longest-term project I’ve ever taken part in, and we saw it through, together, to the end. The challenge now is to get it into more translators’ hands, and to teach more translators how to use it—as well as into publishers’ hands, and to win more of them over to the idea that offering better terms to translators will benefit them as well.

I’m hoping the Authors Guild will begin running online workshops on the translation model contract, the same way they do for their model trade book contract, and that we can find and support translators in learning about it so they can teach others in their local translation communities about contracts. This is one of the issues, I think—that, up to now, knowledge about contracts has not been sufficiently widespread, geographically, with most of it concentrated in New York—probably because that’s where the publishing industry is concentrated and where PEN’s Translation Committee is based, which, again, until this year, had the only model contract for literary translation.

Of course ALTA holds its conference each year, and that’s a great opportunity to reach a lot of translators at once, from all over the country. For several years running now—again, thanks to first Erica Mena and then Lissie Jaquette at ALTA—the Authors Guild has sent someone to take part in the ALTA conference and educate translators about publishing contracts. Also, in 2018 the Authors Guild launched its regional chapters, and we have contacts with translators in some of those chapters already, so that’s another way to reach more translators outside of the New York City area. Either way, education needs to be more consistent and ongoing. In general, too, I hope more translators will realize that complaining is a good place to start—we all start there!—but we can do more than just complain. We can join together and organize.

This brings me to a thought I’ve had often, which is that I’d like to see more translators think of themselves as workers—again, as people who do a job to earn money—and of their work as labor, not only as art, which unfortunately in our society too often carries with it the expectation that it will be unpaid, or that money is not central, the whole “labor of love” trope. Honestly, to insist on translation only as a labor of love, without acknowledging that it’s also a profession, is a hindrance to translators’ efforts to be paid fairly. We dance and dance and dance around the question of pay—I’ve been guilty of it too. It’s a difficult topic to broach, because in the United States we’re taught that it’s impolite to talk about how much we’re paid.

I would also say that I don’t feel I’ve done enough to apply an organizing mindset and bring more people into the work of building the power of translators collectively, rather than just empowering us as individuals. Nobody in the United States has organized translators, in that sense, before. Maybe it can’t be done. I don’t know. The thing is, I’m also passionate about other issues, like racial justice and policing here in New York, where there’s plenty of organizing already going on, and in recent years that’s taken up more of my time. That said, I was recently talking about this with another translator, and there may be a few of us now who are ready to move more in that direction, more toward organizing.

HT: I remember at one point, when you were cochairing the Translation Committee at PEN, you talked a lot about translator pay. You don’t seem to be talking about it so much anymore. And to be fair, it isn’t just you. On social media, for instance, I feel like I hardly ever see translators talk about pay. Why is that?

AZ: Well, the issue of pay for literary translators is particularly thorny. When I first got involved in advocacy, I felt strongly that we needed to establish a minimum rate. In the U.S., however, to set rates would be a violation of antitrust law. At the same time, our labor law prohibits independent contractors from engaging in collective bargaining. This means even if translators were to join a union, the union still couldn’t negotiate rates for us. However, there is a possibility that may change. On December 20, 2021, the Authors Guild, writing on behalf of an informal coalition of creator organizations, filed comments with the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division, arguing in favor of collective bargaining rights for freelance creative professionals. Although translators weren’t specifically named in the coalition’s letter to the FTC and DOJ, I believe we should be included. I haven’t yet had a chance to speak to anyone at the Guild to confirm. If translators had the right to bargain collectively, it could be a game changer.

Nothing is about to happen overnight, though, and in the meantime I’m still not certain that setting a minimum rate is a solution to the problem of literary translators being underpaid. There are two reasons for this. One is that not all translators are actually in the same labor market. For example, if I, as a Czech translator, ask for a fee that a publisher thinks is too high and they decide to find someone else to do the job for less, they can’t turn to a translator from Vietnamese or Urdu, right? They have to find someone who translates from Czech, so supply and demand doesn’t operate across the entire labor force of translators, but only within the labor force of translators of a particular language. The second reason I’m unconvinced a minimum rate will solve the problem of literary translators being underpaid has to do with the debate I saw unfold within the UK’s Translators Association. For years the TA had a statement on its website declaring, “In our experience of reviewing contracts, we find that UK publishers are prepared to pay in the region of £XX per 1,000 words.” While the number of pounds per thousand words varied over time, the formulation remained the same. Many translators—especially those who were starting out and had never negotiated a contract before—found the statement useful, since it established a baseline that they could point to if the rate they were offered was less and say, “Hey, you’re offering me less than ‘the TA rate.’” (That’s how it’s typically referred to: “the TA rate.”) However, in practice it functioned not only as a baseline but frequently also as a ceiling—translators who were more seasoned were frustrated to find that publishers were also unwilling to pay more than “the TA rate.” In this case, we run up against the issue of a labor force differentiated not by language but by experience. Over the course of two or three years, then, in consultation with Society of Authors staff, TA members arrived at a new formulation, which you can find on the TA’s website today: “In our experience, translators and publishers negotiate fees starting in the region of £95 per thousand words.” [emphasis added] Note the shift in language to highlight that a rate is negotiated; this is for me the most important thing to drill into translators’ heads: that a publishing contract is negotiated, not simply “take it or leave it.” Also that this rate is a starting point. The complete statement, beyond this single sentence, points out that “remuneration is a matter for negotiation” and that the fee “may be considerably higher, depending on various factors including the translator’s experience, the timescale for the translation, the difficulty of the prose, the amount of research required and the availability of translation funding.” And the statement goes on to list several other factors that translators should take into account when deciding what is an acceptable fee for any given project.

HT: So is that “the solution,” at least with regard to translator pay?

AZ: I wouldn’t call it “the solution,” but it seems to me the best that can be done under the present conditions, and I’d like to see the Authors Guild publish a similar statement. Meanwhile, I think it’s clear—especially in this moment where we’re seeing so much precarity for so many workers in the United States, along with a really exciting surge in labor organizing and unionization—that we need new thinking about how to ensure that literary translation can be a viable profession economically. Or maybe it can’t be? In which case we still need new thinking about how to ensure literary translators are at least paid fairly.

HT: I realize your work with the Authors Guild doesn’t concern this directly, but what about the issue of diversity in publishing? Or, more to the point, among translators, and in terms of which authors get translated?

AZ: Another great question. I think it’s more useful to talk about equity than diversity, since, as Kavita Bhanot has pointed out, “The concept of diversity only exists if there is an assumed neutral point from which ‘others’ are ‘diverse’” and we know there is no neutral point. That said, although in the past few years there’s been increasing attention to how racism and white supremacy operate in publishing—to how few literary translators of color there are, and specifically Black translators, and to the higher bars and greater obstacles that translators of color, and specifically Black translators, face at every step along the way in comparison to white translators—I’ve seen little discussion of the role that pay plays in this. One of the reasons why publishing in the U.S. is as white as it is (as well as overwhelmingly cis, straight, and non-disabled), is because of the low pay, especially at the entry level. Traditionally, the main way people have gotten into the business is through unpaid, or tokenly paid, internships, and because of racial capitalism (because capitalism is racial), this dynamic is also at work, also visible, in the production and publication of literary translations. In short, a big part of why most literary translators are white is because it pays so little. White people, statistically, because of the racial wealth gap, are way more likely to be able to afford to work as literary translators. So the issue of pay is central in determining who translates. At the same time, it’s important to realize these issues aren’t unique to translation or publishing, but a problem of our economy and society in general, of capitalism.

I don’t want to stray too far afield here. I just get frustrated when I see translators going round and round in circles about the same issues, over and over again, with no recognition or acknowledgment that these problems are societal and systemic; they don’t exist just in publishing or in translationland. So whatever advocacy or organizing we do, whenever possible, needs to keep this bigger picture in mind. I am committed to remaining open-minded about what is the best way forward, and eager to help foster new thinking on how translators (and writers, who could potentially be great allies) might identify where we have common interests with publishers, do some power mapping maybe, and see if there’s a way to make the work of writing, translating, and publishing literature both equitable and sustainable for everybody involved in it.

HT: Alex, this all sounds great in theory, but could we return to what you said about negotiating? Because, speaking for myself and a number of colleagues who I know feel the same way, contract negotiations can be intimidating. A lot of us feel a sense of powerlessness vis-à-vis publishers, where when they send us a contract and we want to ask for a change, our first thought is, “What if they just say no? What if they simply decide that I’m too demanding and move on to another translator? They have other options, and surely someone else will just accept what they’re offering me now.” Do you have anything to say that might help to alleviate some of these apprehensions?

AZ: Sure. It’s a common question and I know from experience it’s on a lot of people’s minds, even if they don’t always say so. So, first of all, you need to know what your priorities are. The Authors Guild Literary Translation Model Contract and Commentary—which is available to everyone for free, whether or not you are a Guild member—states very clearly, “Our advice is that you identify the provisions that are most important to you and concentrate on them.” (To that end, I also recommend the checklist for negotiating contracts that a few of us put together back in 2016 to help translators identify the various terms of a contract that are negotiable and decide which ones matter most to them.) One way in which the AG model contract is a great improvement over the model contract previously published by the PEN Translation Committee is that it has extensive commentary, including discussions of the range of options translators may consider when negotiating particular terms. It isn’t just saying, “You should get this,” or “You must demand this.” It doesn’t replace the expertise of a contract review by Authors Guild staff, but one of our goals in writing it was for translators to be able to use it on their own to understand contracts and guide their decision-making during negotiations. Second, I have never heard of a publisher walking away from a translator once contract negotiations were under way. I’m not saying it’s never happened, but it’s less likely to happen than many translators fear. What I have heard of is a publisher writing to a translator, “Are you available to translate x-and-such book by x-and-such date?” and the translator writing back to say, “Yes, and my fee would be x-and-such dollars” or “my rate would be x cents per word,” or “Yes, but I would need x more weeks or months,” and never getting a reply—apparently because the publisher found someone else to do it for less money or by an earlier date. But most novels—and I should’ve said off the top, what I say in this interview pertains to translations of book-length works of fiction or nonfiction, rather than to poetry or drama—are not rush jobs. So that’s a different situation from one in which there’s already been a conversation or correspondence, some sort of extended back and forth—between you and the publisher, or, say, between the author’s agent and the publisher—to get to the point where the press has sent you a contract. At that point, I think most translators underestimate the degree to which the publisher (or editor) is also invested in working with you, or at the very least is loath to spend the time and go through the hassle of finding someone else instead of you to do the job. You have the trust of the author—and, again, if the author has one, their agent. You have, depending on the circumstances, put substantial work into preparing materials about the book. If you ask for a change in the contract the publisher sends you, they’re more likely to say, “We can’t do that” than “Forget it. We’ll find someone else.” If the publisher says they can’t pay you as much as you want, they may make a counteroffer that’s less than you’re asking for but higher than their initial offer. Or they may simply say (this has happened to me), “We can’t do that,” and then the ball is back in your court to make your own counteroffer, or, “How about a higher royalty if the book sells more than x copies?” (i.e., if it sells better than the publisher is expecting), or “How about more time to do the book then?” (if you’re working on multiple projects simultaneously to pay the bills), or “How about you give me a higher percentage of the receipts from licensing of subsidiary rights?” Or even just “How about more free copies then?” (Really, translators should have workshops available to them on negotiating, the same way we have them on translating itself—another project to organize!) My third point concerns “the human factor.” Ask yourself: How am I going to feel working for people who intimidate me? Does this book really mean that much to me? Do I have no other options for income at the moment? It may be that it’s worth it under the circumstances. But it’s important always at least to ask ourselves these questions.

HT: What can I do to help?

AZ: If you are a professional literary translator, meaning that you rely—at least in part—on your income from literary translation to earn your living, you should definitely join the Authors Guild. The dues you pay as a member go to support the programs of the Guild, whose staff are constantly overworked and who don’t attract the big-money donors that pro-corporate organizations do—and again, who are the only organization in the country with model contracts for both authors and literary translators. Even if you translate no more than one book a year, the advice you get from the Guild attorney on that single contract review will be more than worth the cost of your annual dues. (Not to mention that dues in professional organizations are tax-deductible.) One other absolutely invaluable service the Authors Guild provides is that they will write a letter on your behalf to any publisher that violates its contract with you. Several people I know have asked the Guild to intervene in this way, and I can tell you: When a lawyer from the Guild writes a letter, it gets results.

If you aren’t a professional translator, that’s OK too! You can still read and use the Guild’s Literary Translation Model Contract. Share it with all your translator friends. Organize a get-together to study and talk about it. Encourage the publishers you work for to read it and use it as well. And whether or not you consider yourself a professional translator, if you’re negotiating a contract and the publisher asks, “Where did you come up with that?” tell them you got it from the Authors Guild model contract. If you attend a translator workshop or residency that doesn’t include any discussion of contracts, ask why not. Suggest that they add a session on contracts, or at least that they refer participants to the Guild’s model contract, so that translators are aware that the Guild and the translation model contract exist. Also, pay attention to other freelance workers and how they organize to win the working conditions they want. All of the ideas I’ve brought to my advocacy for translators have come from organizers in other fields.

Finally, I want to acknowledge that many literary translators in the U.S. do not rely on their translating work to earn a living. Rather than viewing themselves as professionals, they consider what they do to be a labor of love. I talked about it earlier, so I don’t want to beat a dead horse. Honestly, I understand. All I ask is that people consider how low pay and working conditions restrict who’s able to do literary translation to those who have more privilege and wealth, and how that affects who and what is published. If this is something they care about, I would ask that they too adopt the cause of better pay and working conditions (for all translators, to be clear; not only themselves); and if they don’t care, I just ask that they not make it harder for those who do by claiming that what we want is unreasonable.

Alex Zucker has translated novels by the Czech authors Bianca Bellová, Jáchym Topol, Petra Hůlová, J. R. Pick, Magdaléna Platzová, Tomáš Zmeškal, Josef Jedlička, Heda Margolius Kovály, Patrik Ouředník, and Miloslava Holubová. He has also Englished stories, plays, subtitles, young adult and children’s books, song lyrics, reportages, essays, poems, philosophy, art history, and an opera. Alex is a past cochair of the Translation Committee at PEN America, and his collaboration with the Authors Guild has thus far resulted in the first national survey of working conditions for literary translators in the United States, the creation of a Translators Group within the Guild, and the Guild’s first model contract for literary translation. More at alexjzucker.com.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, January 11, 2022