There Is No Equivalence

Translators Danielle Pieratti, Piotr Sommer, and Jennifer Grotz in Conversation with C. Francis Fisher and Matvei Yankelevich

It’s always distorting in some way. When you go from one language to another there is no equivalence, really, that idea is a myth.

“Colloquy: Translators in Conversation” is an event series based in New York City and sponsored by World Poetry Books. On October 8, 2022, Unnameable Books in Brooklyn hosted Colloquy #1, with Jennifer Grotz, Piotr Sommer, and Danielle Pierratti reading from their translations—Everything I Don’t Know by Jerzy Ficowski (World Poetry, 2021) and Transparencies by Maria Borio (World Poetry, 2022). After the reading, the hosts of the series, Matvei Yankelevich and C. Francis Fisher, engaged the translators in the following conversation, which has been edited for clarity and length.

Matvei Yankelevich (MY): We wanted to start by asking each of you the particularities of your translation processes–for you, Jennifer, what was it like co-translating with Piotr, and for you, Danielle, what was it like working with a living author?

Jennifer Grotz (JG): I’ll jump in and say that before this project I preferred to work with dead authors or translate dead authors. So [having a co-translator was a very] new experience, and I won’t claim that it was always easy.

Piotr proposed the project, and he was a friend of [Jerzy] Ficowski’s, so he knew the work very well. He would assign me batches of about twenty poems at a time that I would work on and make rough drafts of and then our process was deeply collaborative from there. We read the poems in English and Polish and fought over every word. So, it was a long-drawn-out process. I have always felt translation takes me much longer, even working alone, than writing a poem of my own.

To me, that’s a disadvantage, it takes a lot of time and effort. But one of the advantages was that there was this really pleasing experience of one of us being a native speaker of English and the other, Polish, and that really gave us some authority. Though we disagreed a lot, when we finally agreed there was an authority to it which felt very satisfying. That is not an experience I’ve had when I’m translating from the French by myself, so to me this is actually a big plus.

Danielle Pieratti (DP): I was relatively new to translation when I started working with Maria’s poetry, and I think, as someone who was just learning about translation, I felt more comfortable having a living writer because I felt like she would be able to give me feedback on the poems. I think a lot of times when you’re translating, it can feel very isolating because there’s such a small number of people who can actually read both languages and tell you how you’re doing. So having Maria there and being able to work with her really intimately on the poems gave me a lot of reassurance about the final product that I maybe wouldn’t have had if I were working with an author that was no longer living.

MY: I’d like to ask, particularly with regard to Ficowski, how you all chose to maintain a sense of foreignness in the translation, whether it was in place names or by way of neologisms, or by refusing to translate certain terms like verst. Could you speak to that?

Piotr Sommer (PS): I would need to have a look at the specific poem because we made each decision dependent on the context and what the poem was about and how it would work in English.

I assigned specific poems to Jennifer when I was compiling subsequent lists of titles, mostly poems that my English imagination allowed me to believe would get into your language more fluently than others. So, this selection is very much limited by that. I have to add that, because his oeuvre is huge. So much of it relies on the way that Polish works, in terms of phraseology and lexicon, and on how he made it work in new ways. Often, he took a regular phrase from one context and moved it into a new one, or contaminated them, also discovering or rediscovering some literal meanings or playing with false etymologies, or relying on the old language. All of that was very difficult to translate. So, a lot of those ones we simply chose not to translate.

JG: I want to add that in the drafting process, my first attempt would be to try to make it very clear and sort of tame it into English. I would overcorrect, and Piotr would step in and say, “Nope, it’s not that easy. Ficowski is a really textured, difficult poet. We’re not here to smooth it out and anglicize it. We’re here to present that texture.” So, we would fight. That was part of our dynamic, but, interestingly, I think that’s often what poets and translators do while working alone–this was a sort of dramatization or externalization of what I felt I often did working singly, only this time with another person. Once I figured that out, I was much more comfortable with our back and forth.

C. Francis Fisher (CF): I am curious about the sound of each language–particularly the Italian–because of the difficulty rhyming presents in English which doesn’t exist the same way in the source language. How did you deal with the sound-sense problem of translation that is especially present in poetry?

DP: I thought about this a lot as I was translating. I had a choice to make whenever there was a corresponding Latinate word in English, and I often chose not to use it because there would have been a formality to these words in English that might misrepresent the Italian.

[As English speakers] we often have a choice between a more ordinary, often lower-register Anglo-Saxon sounding word, versus a Latinate, romance-language version of it. And for us, those romance words often have a level of formality that they don’t necessarily have in Italian.

Also, I feel very attached to the sound of English. As a poet, you fall in love with the sounds [of your language] and you become familiar with them. I wanted to transform the poems, in a way, to take advantage of English’s linguistic or etymological dissonances in order to capture some of the dissonance that I was seeing, maybe not in the words of the poems, but in the imagery, in the rhythms, and in the fragments. Bringing the work into English allowed me to do that.

PS: That’s a hard thing to do because Polish is a completely different world of sounds. I don’t think similar sounds can be reproduced in English. For example, in Polish, “deszcz” means rain and formally it’s just one syllable, but is it really one syllable, when in order to pronounce it, you need to produce the sound of the vowel “e”, and you need to speak out the sound “sz” and the sound “cz”? When you say this “one syllable word” as it should be spoken, it’s a very long one syllable. Polish has thousands of words like this, which not only means that the world of sounds is different, but its syllabics as well.

MY: Piotr and Jennifer, I’d like to ask about translating tone. Ficowski has this way in which, partially as a response to Nazi atrocities and the Holocaust, he refuses the possibility of knowledge in favor of dark humor. He writes about those times and those who took part in them without ever imagining he knew how they felt. Can you speak to that tonality?

PS: Your acknowledgement of this tone is very apt, and I think part of what really differentiated Ficowski from other Polish poets of his time. For example, I think of Milosz and his famous line, “What is poetry which does not save nations or people?” He had this grandiose idea of what poetry could or should do.

Ficowski’s perspective was very different – he was interested in “unsurvivors,” those who did not survive. Part of his poetics stems from his famous line “I was unable to save a single life.”

MY: Right, these aren’t poems that want to save a nation, they don’t sermonize at all but prefer leaving it up to the reader. Jennifer, did you want to add something to this?

JG: I really agree with the observation, and I find it quite distinctive in his work. It’s part and parcel of his radical imagination or empathy. I think it has something to do with the quality of his mind and imagination.

MY: Thank you. Danielle, I wanted to ask you: this book is so much about reflections. It’s called Transparencies, but it’s also about in-between spaces, and there’s a two-part structure to many of the poems. Thinking about reflections, glass, and screens, could you maybe speak to these ideas’ relationship to translation?

DP: The title of the book is Transparencies, and we actually made this decision because in Italian it is just Transparency in the singular. I switched it to reinforce the materiality of the transparencies that are in the book. There are screens, film, computer screens, cameras, video, all of these different media that she’s referencing in order to talk about this in-between space, this liminal space where people come into contact with each other. There’s something disorienting about understanding people and meeting people and interacting with people through various kinds of screens or even glass.

What I love about the way Maria uses these themes is that there are many poems in which her own complicity in that is implied as a writer. She is also a kind of medium, just like film is a medium. And as we all know, with translation, that glass is never transparent. It’s always distorting in some way. When you go from one language to another there is no equivalence, really, that idea is a myth.

It struck me today, actually, as I was thinking about this conversation, that really every language is a kind of medium, is its own medium. The word “language” is almost inadequate when it comes to conveying how different one language is from another. And in showing that when you move into a different language, you’re moving into a whole new set of tools that can open up a lot of possibilities, but also limit you in a lot of ways. I find that those limitations are really exciting. So, I think the parallels to translation, maybe like Maria’s experience of the transparencies, is a disorienting one in her work. But I think for translators that sort of challenge of conveying information from one side of the glass to the other is exciting and liberating.

Transcription by C. Francis Fisher.

Danielle Pieratti is the author of Fugitives (Lost Horse Press), winner of the 2017 Connecticut Book Award for poetry, and the translator of Italian poet Maria Borio’s English-language debut, Transparencies (World Poetry). Her most recent poems and translations have appeared in Meridian, Ambit, Mid-American Review, Words Without Borders, and Asymptote.

Jennifer Grotz is the author of four books of poetry, Still Falling (Graywolf Press), Window Left Open (Graywolf), The Needle (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), and Cusp (Mariner Books), as well as translator of two books from the French: Psalms of All My Days (Carnegie Mellon), a selection of Patrice de La Tour du Pin; and Rochester Knockings (Open Letter), a novel by Hubert Haddad; and co-translator from the Polish of Jerzy Ficowski’s Everything I Don’t Know (World Poetry), winner of the 2022 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation. She teaches at the University of Rochester and directs the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conferences.

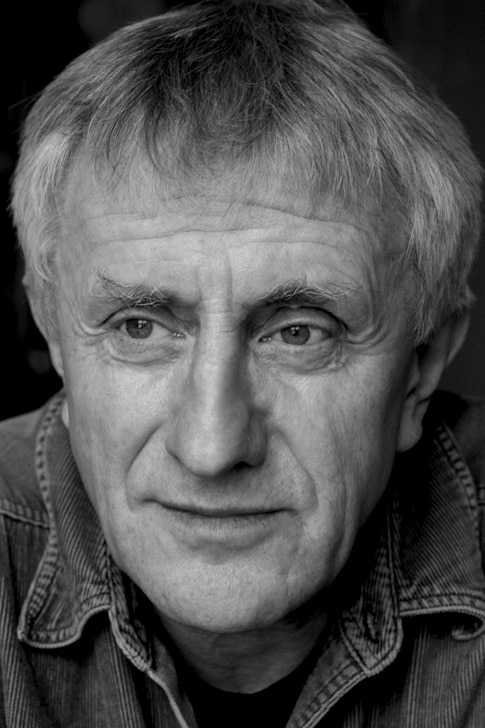

Piotr Sommer is a Polish poet, the author of Things to Translate (Bloodaxe Books), Continued (Wesleyan), and Overdoing It (Trias Chapbook Series). He has won a variety of prizes and fellowships, and has taught poetry at American universities. With Jennifer Grotz, he co-translated Jerzy Ficowski’s Everything I Don’t Know (World Poetry), winner of the 2022 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation. He lives outside Warsaw and edits Literatura na Świecie, a magazine of foreign writing in Polish translations.

C. Francis Fisher is a poet and translator based in Brooklyn. Her writings have appeared or are forthcoming in the Raleigh Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, and the Los Angeles Review of Books among others. Her poem, “Self-Portrait at 25,” was selected as the winner for the 2021 Academy of American Poets Prize for Columbia University. She teaches undergraduate composition at Columbia University and is the curator and moderator of “Colloquy: Translators in Conversation.” Her translation, In the Glittering Maw: Selected Poems of Joyce Mansour, is forthcoming from World Poetry Books in 2024.

Matvei Yankelevich is a poet, translator, and editor. His translations include Today I Wrote Nothing: The Selected Writings of Daniil Kharms (Overlook) and Alexander Vvedensky’s An Invitation for Me to Think (NYRB Poets; with Eugene Ostashevsky), winner of the 2014 National Translation Award. In the 1990s, he co-founded Ugly Duckling Presse, where he edited and designed books, periodicals, and ephemera for more than twenty years. As of 2022, he is editor of World Poetry Books, a nonprofit publisher of poetry in translation.

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, April 18, 2023