Reading for Comic Performance Between the Lines

Part I: Toward a Taxonomy

by Jody Enders

Faced with the silent, motionless theatrical page, the translator reads between the lines for performance, the modalities of which are practically infinite but infinitely rewarding.

Picture this—and live theater requires that you actually do picture this:

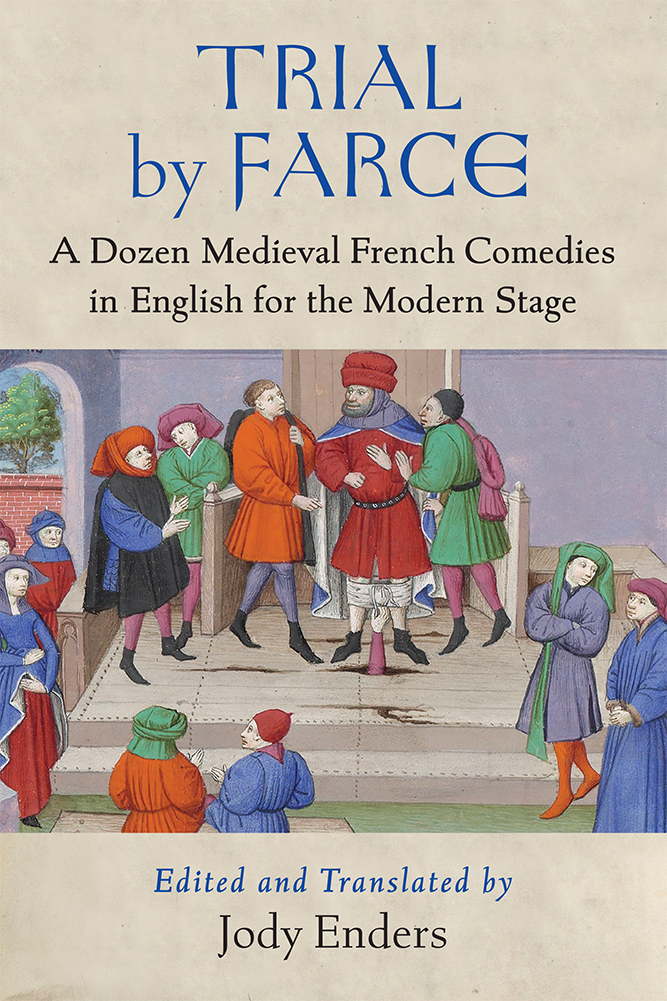

Outraged that her daughter’s marriage has yet to be consummated after an entire month, a mother demands to know whether her son-in-law has all his parts in working order (organisé de ses membres). “Where are your bros, bro?,” asks Thomasina in the anonymous Not Gettin’ Any (Farce nouvelle très bonne et fort joyeuse du Nouveau Marié qui ne peult fournir à l’appoinctement de sa femme). The unnamed Newlywed shoots back both verbally and physically: “Good God Almighty, woman, in your face! Check out these beautiful boys! How’s that for a pair?” But just what kind of demonstration ensues? Is the denouement of the play a denudement?

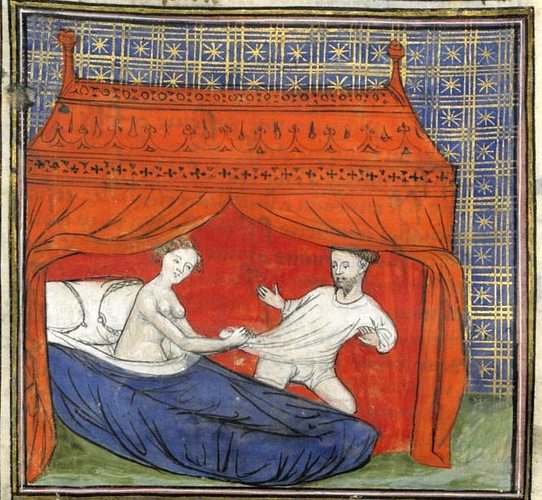

Seduction of Lancelot. Gautier Map, Livre de messire Lancelot du Lac, ca. 1401-1425, fol. 33. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

When pondering a similar conundrum in his recent edition of Chick Latin, “Maître Antitus” (aka Thierry Martin) offers some guidance as to how a lascivious professor might reply to the female students of the Farce nouvelle des femmes qui apprennent à parler Latin. As the women debate the best legal remedy for a sexless union, perhaps Monsieur le Professeur might tender a “private” display of what he himself is packing—so long as he is seated in profile, warns Martin, thereby shielding the audience from what the coed is forced to behold.

But what are we to make of another set of stage directions crafted by André Tissier, the brilliant editor of sixty-five Middle French farces in his thirteen-volume Recueil de farces françaises (Droz, 1986-2000), all of which he translated into modern French in the four-volume Farces françaises de la fin du Moyen Âge (Droz, 1999)? Picture now the title character of Slick Brother Willy, a promiscuous monk who beats a hasty retreat from a married woman’s bedchamber because—what else?—her husband arrives unexpectedly. When the Franciscan bolts sans underwear, Willy proposes to use his bare hands to support his “ball-sac” (sac à couilles). Willy or won’t he? The Middle French was so graphic that the original nineteenth-century editor of Ancien théâtre françois (Paris, 1854–57) declined to transcribe the key word. “I guess I’ll just have to make a fist,” ejaculates Willy, “and take my dick, Brother Willy, in my own two hands. Nature’s own jockstrap!” (Je prendray mon vit à mon poing; / Mes mains me serviront de brayette). But rejecting the words doesn’t come anywhere close to resolving the visual matter of what is happening on stage. How are we to get Willy off stage? Here is Tissier’s proposition in his modern French translation of Frère Guillebert: Willy “makes a sketchy sign of the cross that degenerates into a caress of his groin-area” and then “hides his organ with his hand.” Oh, really? What do you suppose that looked like?

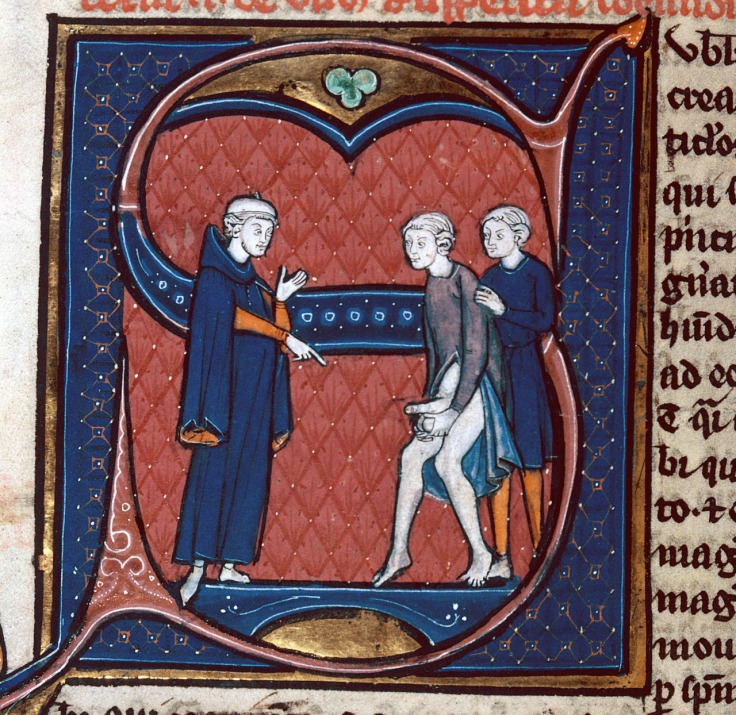

Avicenna, Canon medicinae (translation of Gerard of Cremona). Paris 13th c. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque municipale de Besançon. MS 457, fol. 254v.

And what in the name of all that’s holy is to be done when a priest reassures the nymphomaniacal penitent of Blue Confessions that her sins constitute good works? When he praises Margot of La Confession Margot for ministering to a wayward brother’s “sausage,” we presume that he means, “You were most charitable to have warmed up that poor creature.” What he says, though, in the present tense, is this: “How charitable you are” to warm up—as in, to be in the process of warming up—this poor creature. What he says is not “vous aviez” but “Vous avez grand devotion / D’eschauffer celle pouvre beste” (ID, 65). A gerund helps to capture the double meaning: “[Oh God, oh, the devotion!] Warming up that poor creature!” (ID, 74). But is Bernard Faivre’s stage direction workable? In the Répertoire des farces françaises (Paris, 1993), Faivre goes so far as to opine that Margot “is replaying on the Confessor the same manipulations with which she [had earlier] gratified the hermit’s ‘sausage’” (111). And amen to that. But does the translator know what the meaning of “is” is? Or, to be exact, what the meaning of “are” was?[1]

In endeavoring to create stageable translations of these plays, I frequently found myself hearing the recommendation of Rita from Willy Russell’s Educating Rita. When asked how she would resolve the staging difficulties of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, Rita suggested: “Do it on t’radio.” What a great idea … were it not for the fact that there was no radio to amplify the mostly anonymous farces of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century France; they were staged events, not solely “plays for voices.” In confronting a vast repertoire of more than two hundred plays—more extant than in any other European vernacular and spanning the two historical periods known as the Middle Ages and the Renaissance—the translator is thus obliged to search for other ways to impart all that seeing and hearing, looking and listening.

Extreme though the four examples above might be in their potential for pornography (ID, 9-14), they direct our attention toward a fundamental condition of theater: performance changes everything. Theater is a living art form in which actions regularly speak louder than words and in which vocal inflection can mean everything. For that reason, understanding—and translating—theater depends as much on what we see on the page as on what we don’t see. Needless to say, the translator of oral literature or poetry is all too aware of the importance of reading for oral, aural, and visual meaning. A troubadour sings, declaims, or gesticulates before a crowd; a medieval book of love lyrics, among them, “J’ay prins amours” from Okay, Cupid (TBF, #9), is presented in the form of a heart in the glorious Chansonnier de Jean de Montchenu. (Guillaume Apollinaire was scarcely the first to configure poetry spatially in his Calligrammes of 1918.)

“J’ay prins amour.” From the Chansonnier cordiforme de Montchenu. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

“Paysage” from Calligrammes by Guillaume Apollinaire (1918)

But theater supplements that semiotic richness with the material conditions of performance, to which the translator also responds. What did the play look like? What did it sound like? Or, in the universe that gave us the title cut of my Farce of the Fart and Other Ribaldries (Penn, 2011; hereafter FF), what did it smell like? Inasmuch as theater calls for imaginative engagement with oral, aural, visual, physical, and material potentiality, the translator has necessary recourse to what Philip Auslander termed “liveness” in his book of that title (Routledge, 1999). Alert as much to the nonverbal as to the verbal material, the translator of theater owes, at the very least, a triple duty to the auditory, visual, and linguistic stimuli that bombard the senses simultaneously during performance. Whence my emphasis below on not just the proverbial right word (le mot juste) but just the right stage action (le geste juste).

With or without a surviving script, a play text is, by and large, a blueprint, a code to be cracked by the multiple individuals who combine forces to make theater. With each performance, producers, directors, designers (of sets, costumes, lights), actors, and audiences inflect an author’s (or authors’) already inflected work through sight, sound, and movement—and in ways that vary from place to place, time to time, person to person, and within the same person. It is in that sense that theater itself is always interpretation, always translation, always adaptation. Faced with the silent, motionless theatrical page, the translator reads between the lines for performance, the modalities of which are practically infinite but infinitely rewarding. While no translator can hope to account for the incalculable variations, it is nonetheless possible—and desirable—to convey all that potentiality. Nor is so doing tantamount to confusing virtual staging with real staging. It is, rather, to acknowledge that the virtual implies the actual and vice versa. As Marco De Marinis wisely advises, virtual staging is “inscribed or hidden in the text” while real staging refers to actual performances past (Semiotics of Performance [Bloomington, 1993], 22; his emphasis).

In Part I of this essay, I argue that somewhere between past, present, and future performances, there lies a rich interpretational reckoning to be had with what and how theater means. For the translator, that involves what I call “virtual dramaturgy”—a means of conjuring a range of performances to be seen in the mind’s eye and to be heard in the mind’s ear. In a word, I contend that there is no true translation of theater without a theory of dramaturgical practice. In Part II, I then turn to how that virtual dramaturgy can be categorized, the better to render the sights, sounds, and kinetics of the stage. There, I lay out a bona fide taxonomy for a more holistic translational practice designed to do justice to the collaborative medium that is theater.

The Parlement de Paris deliberating matters of law under Charles VII, ca. 1450. By Jean Fouquet for Boccaccio’s Des Cas de nobles hommes et femmes (French translation by Laurent de Premierfait).

Le Mot Juste, le Geste Juste

For the most part, the Middle French farces were authored anonymously by lawyers and legal apprentices with a distinct predilection for blistering satires of social institutions. They belonged to the “Basoche,” a society that was founded in 1303 and flourished between 1450 and 1550, at one point boasting upwards of 10,000 “Basochiens.” What is more, their comedies were among the first literary works to attract early publishers eager to take advantage of the lucrative new markets awakened by the printing press. From the outset, therefore, that phenomenon foretells the challenges of transferring live or unscripted drama to the page. Farce plays out in the breathless pace of primarily octosyllabic verse—one-two-three-four; one-two-three-four; only-eight-beats; not one beat more! (Unless, of course, somebody loses count, which happens a lot.) But in addition to the translator’s usual hurdles—the resonance of all the slang, the dialects, the allusions to long-forgotten historical events, the pop culture—farce tends to revel in an audiovisual extravaganza of singing, music, dancing, mime, and slapstick. So it was that Tissier remarked that “the text seems only a support; and what one could easily read inside of half an hour might well justify a performance of one hour” (Recueil de farces, 1: 43). How, then, is the translator to see all the gesture, movement, dancing, props, and set design? What about hearing the intonation, volume, and pacing? the long-lost melodies or the lyrics that were customarily cued by song titles alone? The problem is that, for all their obstreperous verve, the loquacious farceurs are curiously circumspect when it comes to providing stage directions or didascalia.[2]

Readers of Hopscotch are doubtless on intimate terms with the expression le mot juste: that maddeningly elusive “just the right word” or phrase that seems to yield the perfect translation. (I found one, I thought, in Blind Man’s Buff [Farce du Goguelu], where I translated the game of broche-en-cul—“stick-up-the-asshole”—as “shit-kebabs” [FF, 179; 428].) But in performance-based media, the translator seeks to locate not only just the right word but just the right stage action. It’s a question of both le mot juste and le geste juste. That would come as no surprise to any art historian, nor to the storied medieval historian Jacques Le Goff, who postulated that “the body provided medieval society with one of its principal means of expression. … Medieval civilization was one of gestures” (Medieval Civilization, trans. Julia Barrow [Blackwell, 1988], 357). From classical rhetorical treatises to Jean-Claude Schmitt’s La Raison des gestes dans l’Occident médiéval (Paris, 1990) to The Cultural History of Gesture: From Antiquity to the Present Day (eds. Jan Bremmer and Herman Roodenburg [Cambridge, 1991]) to E. Jane Burns’s Bodytalk: When Women Speak in Old French Literature (Penn, 1993) to Adam Kendon’s Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance (Cambridge, 2004) and thereafter, body language throughout history has been studied extensively by theorists of theater, dance, art, and communication. As early as the first-century Institutio oratoria, Quintilian noticed that gesture does far more than amplify meaning: It can genuinely stand in for language. “Signs take the place of language in the dumb,” he wrote (XI, 3.66), and more pointedly: “other portions of the body merely help the speaker, whereas the hands may almost be said to speak. Do we not use them to demand, promise, summon, dismiss, threaten, supplicate, express aversion or fear, question or deny?” (XI, 3.86). It turns out that all that bodytalk must be visible—virtually visible—to the translator.

The same holds true for sound as communication, sound as action, and sound as single-, double-, or triple-meaning. Characters and objects “speak” nonlinguistically each time somebody onstage grunts, screams, laughs, or weeps, and each time an object crashes or creaks. This is farce: all manner of noise is emitted. But, as we shall see in Part II, paramount to the translation of theater in general and of comedy in particular are the moments when language, sight, and sound come together or, for that matter, diverge. Naturally, this occurs in the wordplay that one expects of comedy (le jeu d’esprit). But, to borrow Patrice Leconte’s turn of phrase from Ridicule, his witty 1996 film about wit, it occurs in gestural play too (le geste d’esprit). Farce routinely amplifies its nonstop wordplay by means of the physical and visual humor of the geste d’esprit—albeit never flagged as such by explicit stage directions. That said, we have a good analogy for the practice in American Sign Language, as detailed by Professor of Deaf Studies Don Grushkin in a media post: “There are also true ASL puns which play off the linguistic principles of ASL. For example, the little finger is often used to symbolize things that are small or thin. If asked whether one understands,” he continues, one would normally sign “understanding” with the index finger; but “in the case of a person who is struggling to understand the concept, they might sign ‘understand’ using the pinky finger instead. There are a few other examples of this sort of wordplay that I have seen, and I consider these to be true ASL puns since there is no connection with English in any of its forms in these.”[3] Visual punning is integral to the comic theater; and in that respect, it belongs to the translator’s craft. It too must be translated, but how? Still more vexing: If a linguistic and corporeal solution can be found, is it still funny at some five centuries’ remove? In early French comedy, there’s the rub.

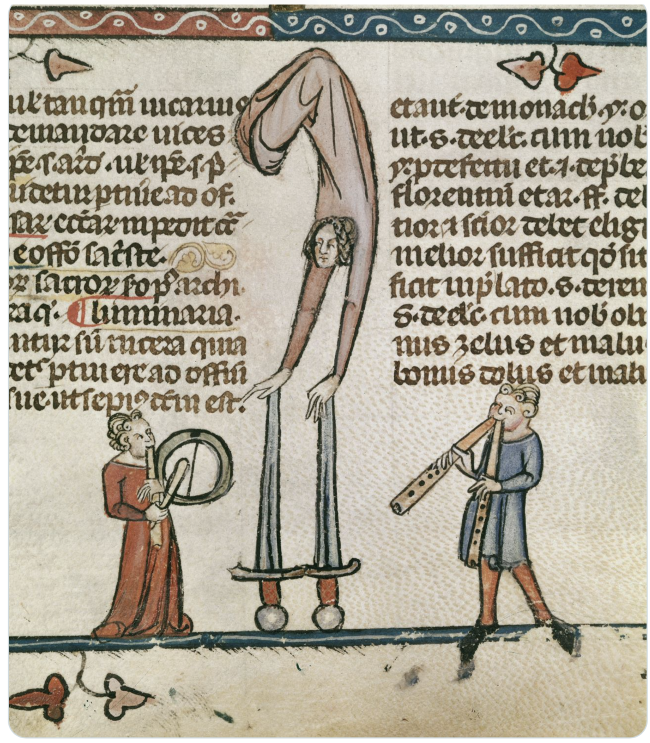

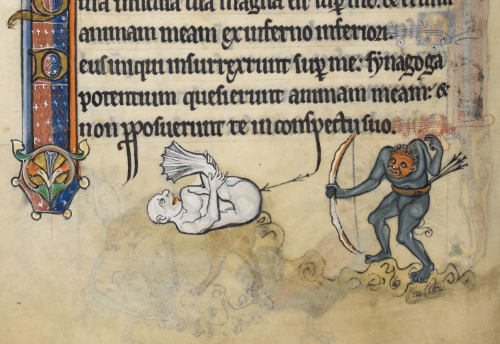

Acrobats, mimes, and musicians in the margins. Courtesy of the British Library, Royal MS 10 E IV. The Decretals of Gregory IX, edited by Raymund of Penyafort (or Peñafort), ca. 1300-1340, fol. 058r.

As a genre, farce is notorious for its relentless obscenity, its Three-Stooges-style violence, its over-the-top sexism, its ethnocentrism, and its classism, and that’s just for starters. It is so politically incorrect that the selfsame humor that once made it a runaway hit is unlikely to stand the test of time. It thus behooves us to ask: Should it stand that test? Would anyone in their right mind wish to stage these plays in our own era? Obviously, I think so, and I hope so. All the more so in the current political climate, where satire has paid a hefty price at a time when we’ve never needed it more. Already back in 2018, Andrew Kay was moved to observe for the Chronicle of Higher Education that the contemporary satirist must reckon with a “cluster of menaces” that tend to “repel efforts at humor” (“The Joke’s Over: Academics Are Too Scared to Laugh”). The sheer scale of the intolerance, he averred, “can hector him into muteness.” To which I would add: her too.

What’s funny today is tragic tomorrow; and, per the adage that “comedy is tragedy plus time,” what was tragic yesterday can be funny today. I submit that, thanks to virtual dramaturgy, the translator is better positioned to read, see, hear, understand, and translate absence and silence. In fact, the unseen and unheard of the printed page can often be what matters most, leading to the following irony: Sometimes, in the translation of theater, the very language that is our stock in trade might not be the most significant element at all, paling by comparison to ephemeral sights and sounds. On that subject, the late, great Stephen Sondheim expressed himself as profoundly as he did beautifully. When asked whether he called himself a poet, Sondheim rejected the notion in a way that speaks eloquently to the predicament of the translator as dramaturge:

What has to be considered—and what not enough people who write dense lyrics consider—is that there’s a great deal going on besides the lyric. There’s music, there’s costumes, there’s lighting. There’s a lot of things to listen to and look at, and therefore the lyric must be, in that sense, simple. It can be full of complex thoughts, and it certainly can have resonance, but it must be easy to follow. That is not true for poetry. Poetry need not and probably often should not be easy to follow. (HBO’s Six by Sondheim; 2013; ca. minute 41:01)

With a new set of prolegomena in place, we can restore some of that resonant complexity as we accept theater’s standing invitation to adapt it to different contexts and different times. We can do so, moreover, in such a way as to drive home the message that silence needn’t always mean what we think it does. Quite to the contrary, silence can—and should—speak volumes in comedy, where it can translate into something extraordinary. Nor, in a set of misogynistic pieces revived for the #MeToo era and beyond, need silence perforce denote consent to misogyny. After all, listening for the silence of what is not there is what launched feminist literary criticism in the first place. It is also consistent with Lawrence Venuti’s compelling claim about adaptation in film: “Translation can be regarded as intercultural communication only if we recognize that it communicates one interpretation among other possibilities.” Nowhere is that more true than in the theater, to which his subsequent comment is germane: “Translation enacts an interpretation, first of all, because it is radically decontextualizing” (“Adaptation, Translation, Critique,” Journal of visual culture 6.1 [2007]): 29).

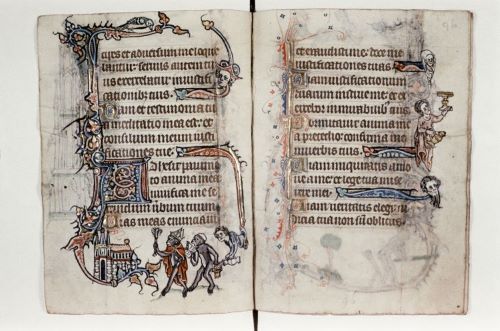

In the end, a virtual dramaturgy of the absent reanimates what is transhistorical in theater. Furthermore, it does so through translations that are philologically accurate yet principled in their stage-friendliness, and no less playable and pleasurable. In the taxonomy of Part II, I propose specific ways of reading for those myriad extralinguistic elements that contribute to theatrical meaning. The seventeenth-century philosopher Blaise Pascal famously admitted that “the eternal silence of the infinite spaces [of the heavens] terrifies me” (Pensées, 1670 ed., 2.206). That’s as good a description as any of how the translator of theater might feel when, grappling with the performative silence of the printed or virtual page, she endeavors to recuperate the long-lost traces of meanings and ephemera. In practice, the terrifying silence of the theatrical page metamorphoses into a space of boundless artistic creativity and potentiality. Once we draw upon the transformative power of performance to adapt, to alter, to interpret, and even to subvert, we rediscover through translation the delights of early humor. And, lest that prospect repel some translators, suffice it to recall that subversion is wholly in keeping with the spirit of medieval manuscript life and culture. From the festive Feast of Fools, during which high and low classes traded places, to the most exquisitely illuminated liturgical texts, social reversal was the order—and disorder—of the day. Meet the farting or pissing creatures, ecclesiastical apes, and sexually positioned individuals who, from the margins of psalters, thwarted and repelled any apparent theological message endorsed by the text.

Rutland Psalter, c. 1260. Courtesy of the British Library, MS 62925, f. 87v.

Ecclesiastical apes from a Psalter, Bodleian MS Douce 6, fol. 95v. Courtesy of Oxford, Bodleian.

More ecclesiastical apes from the same Psalter, fol. 123v. Courtesy of Oxford, Bodleian.

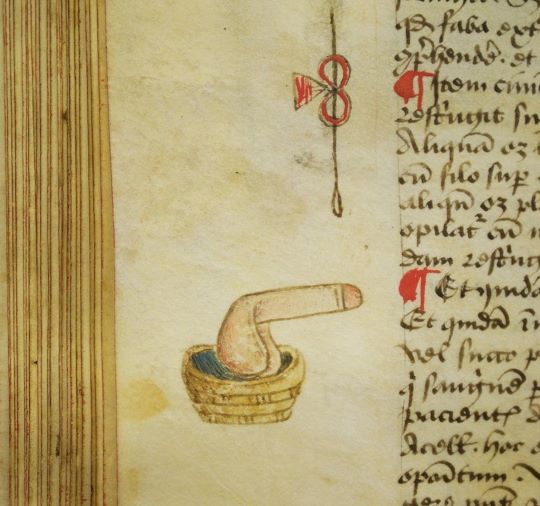

And let’s not get started on how students annotated their liturgical reading material. Nota bene, indeed. Such is the world of farce. Such is the world of the translator committed to recapturing and reawakening the spirited, multisensory experience of the comic theater.

A phallic nota bene marker in the margins of John Arderne’s fifteenth-century treatise, the Mirror of Phlebotomy & Practice of Surgery. Courtesy of Glasgow University Library MS Hunter 251 (U.4.9), fol. 73v.

NOTES:

[1] My translations of the plays above appear here: Not Gettin’ Any, #1 of my Trial by Farce, hereafter TBF (Michigan, 2023); Slick Brother Willy (#11) and Blue Confessions (#2) in Immaculate Deception, hereafter ID (Penn, 2022); and Chick Latin is projected for my fifth volume of translations, tentatively entitled “Whorticulture” and Other Classroom Farces. The farces themselves, many dating from the fifteenth century, are preserved primarily in four sixteenth-century collections or “pseudocollections” (recueils factices), i.e., a group of plays printed separately but later bound together, usually in the sixteenth century: the Recueil Cohen or Recueil de Florence, the Recueil Trepperel, the Recueil du British Museum, and the Recueil La Vallière.

[2] The history of stage directions is intriguing in and of itself. See, e.g., Tiffany Stern’s “Stage Directions,” in Book Parts, eds. Dennis Duncan and Adam Smyth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019): 179-89.

[3] Grushkin posted here to Quora: https://qr.ae/prJt0K (accessed 9 March 2023). You can see an example of an ASL pun here: https://www.handspeak.com/word/6694/.

Jody Enders, Distinguished Professor of French at UCSB, is a past Guggenheim fellow and the prize-winning author of Rhetoric and the Origins of Medieval Drama (Cornell, 1992), The Medieval Theater of Cruelty (Cornell, 1999), Death by Drama and Other Medieval Urban Legends (Chicago, 2002), and Murder by Accident (Chicago, 2009). Her multi-volume translation series of Middle French farces thus far includes The Farce of the Fart and Other Ribaldries (Penn, 2011), Holy Deadlock (Penn, 2017), Immaculate Deception (Penn, 2021), and Trial by Farce (Michigan, 2023). According to the late great Terry Jones of Monty Python, she is “a great champion of comedy at its most vulgar and hilarious!”

Originally published on Hopscotch Translation

Tuesday, July 18, 2023